Key points

- PEP is used to prevent HIV after a potential exposure.

- Any licensed prescriber can prescribe PEP.

- Baseline assessment is required for people beginning PEP.

- Use CDC's comprehensive guidelines for prescribing PEP.

Recommendations

PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis) is the use of antiretroviral medication to prevent HIV in a person without HIV who may have been recently exposed to HIV. Exposure typically occurs through sex or sharing syringes (or other injection equipment) with someone who has or might have HIV. Nonoccupational post-exposure prophylaxis (nPEP) is a term used to specify that the exposure was not work related.

Exposure to HIV is a medical emergency

HIV establishes infection very quickly, often within 24 to 36 hours after exposure.123 Evaluate patients rapidly for PEP when care is sought ≤72 hours after a potential exposure. Determine HIV status in patients being considered for PEP using rapid combined antigen/antibody or antibody blood tests.

If rapid HIV blood test results are unavailable and PEP is indicated, administer the first dose of PEP immediately. PEP can be stopped later if the person has HIV or if the source of the exposure is determined not to have HIV.4

PEP is not recommended >72 hours after exposure

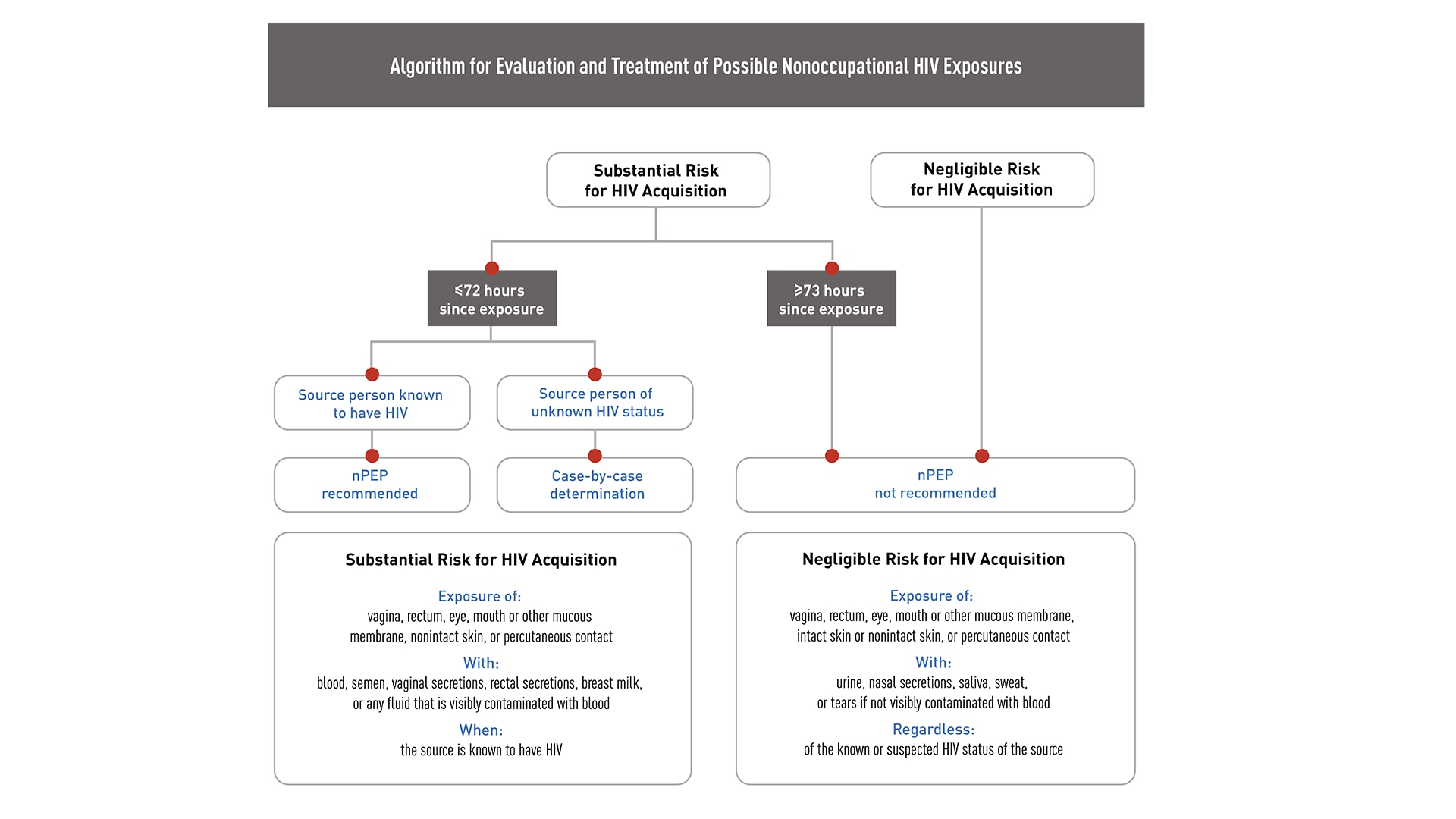

Consider initiating PEP in people whose vagina, rectum, eye, mouth or other mucous membrane, nonintact skin, or perforated skin (e.g., needle stick) came into contact with body fluids from a person with HIV within 72 hours before they sought care. If the exposure source's HIV status is unknown, make a case-by-case determination.

People who have frequent, recurrent exposures to HIV through sex or injection drug use should be considered for intensive risk-reduction interventions and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). If the most recent recurring exposure was within the 72-hour window before evaluation, PEP may be indicated, and the patient can be prescribed PrEP after taking PEP for 28 days.

Any licensed prescriber can prescribe PEP

Emergency medicine physicians are among the most frequent prescribers of PEP, given the need for immediate treatment after exposure. If you work in an ambulatory care practice, ensure that your patients who do not have HIV and report HIV risk factors are aware of PEP and know how to access it after-hours.

Algorithm for evaluation and treatment of possible nonoccupational HIV exposures

Have questions or need assistance prescribing PEP?

If you are inexperienced with prescribing or managing patients on antiretroviral medication, or if information from the exposure source indicates the possibility of antiretroviral resistance, consult with an infectious disease or other HIV care specialist before prescribing PEP to determine the correct regimen—but only do this if these specialists are immediately available.

Similarly, consulting with specialists who have experience using antiretroviral drugs is also advisable when considering prescribing PEP for certain people, such as pregnant people, children, and people with kidney disease.

However, if such consultation is not available, initiate PEP promptly and, if necessary, revise after consultation is obtained.

Evaluation

Baseline assessment is required for individuals beginning PEP.

CDC's Updated PEP Guidelines recommend the following baseline screenings before initiating PEP:

HIV rapid test at baseline. If the baseline rapid test indicates the patient has HIV, do not initiate PEP. If rapid HIV baseline testing is not available, start PEP immediately. Oral HIV tests are not recommended for PEP evaluation.

Pregnancy test. Perform a pregnancy test if the patient could become pregnant, is not using highly effective contraception (e.g., intrauterine devices or other long-acting reversible contraceptives, oral contraceptives, or properly used condoms), and has vaginal exposure to semen.

Serum liver enzyme test.

Blood urea nitrogen/creatinine test.

Sexually transmitted infection screening. For patients being evaluated for PEP because of a sexual encounter, test for chlamydia and gonorrhea at each site of potential exposure using nucleic acid amplification tests and do a blood test for syphilis.

Hepatitis B (HBV) test. Including HBV surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody.

Hepatitis C (HCV) antibody test. Administer PEP if indicated, even before you receive all testing results. There are few absolute contraindications to the recommended PEP regimen. All medications in this regimen have minimal drug-drug interactions. In almost all cases, you should prescribe the first dose of a PEP regimen before obtaining further consultation.

Treatment options

Two PEP regimens are available

Prescribe all people offered PEP a 28-day course of a three-drug antiretroviral regimen.* For PEP to be effective, patients must take the medication as prescribed. To support this, select regimens that minimize side effects, the number of doses per day, and the number of pills per dose.

The preferred PEP regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents is

tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)(300 mg)

+

emtricitabine (F)(200 mg) once daily

PLUS

raltegravir (RAL)(400 mg) twice daily

or

dolutegravir (DTG)(50 mg) once daily

An alternative regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents is

TDF (300 mg)

+

F (200 mg) once daily

PLUS

darunavir (DRV)(800 mg)

+

ritonavir* (RTV)(100 mg) once daily

* RTV is used with some drug combinations as a pharmacokinetic enhancer to increase the trough concentration and prolong the half-life of DRV and other protease inhibitors. It is not considered part of the drug combination.

Alternative regimens may be used in cases of potential HIV resistance, toxicity risks, preference, or constraints on the availability of particular medications. In those cases, seek consultation with other providers knowledgeable in using antiretroviral medications for similar patients (e.g., children, pregnant people, people with comorbid conditions).

Be aware that abacavir sulfate should not be prescribed in any PEP regimen because the prompt initiation of PEP does not allow for genetic testing for the HLA-B*5701 allele, which is associated with a hypersensitivity syndrome that can be fatal.

PEP is a safe method for HIV prevention

The current preferred regimen is generally safe and well tolerated.56 Patients usually experience only mild side effects on the preferred PEP regimen. Most importantly, PEP is only taken for 28 days. In almost all cases, the benefits of HIV prevention outweigh any other risks posed by the medication. In a meta-analysis of 24 PEP-related studies, including 23 cohort studies and one randomized clinical trial, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fatigue were the most commonly reported side effects.7

PEP isn't right for every patient

People who are already using PrEP typically do not need PEP if they experience a potential HIV exposure while taking their PrEP medication as prescribed. If they may not have taken their PrEP medication as prescribed, review CDC's recommended antiretroviral management options.

PEP is not recommended for people whose exposure occurred more than 72 hours before they sought treatment. PEP is unlikely to be effective after this time.

PEP is not recommended for people who were exposed to non-blood-contaminated secretions, such as urine, saliva, sweat, tears, or nasal secretions, as their risk of getting HIV is very low.

Many studies have demonstrated PEP's effectiveness

PEP was first attempted for HIV prevention in the 1980s among health care workers who experienced occupational exposures. This type of PEP is now called oPEP, to differentiate it from PEP used after exposures that were not related to work, or nPEP. At that time, only AZT (zidovudine) was available.

Anecdotal evidence of success began to accumulate, leading to the first formal study of PEP effectiveness, a case-control study of occupational exposures. This study demonstrated an 81% reduction in HIV infection in those who received AZT alone compared with those who did not receive any treatment.8 PEP was proposed for nonoccupational exposures more recently.

Additional evidence supporting PEP includes:

- · Its biologic plausibility (based on animal studies).12

- · The efficacy of antiretrovirals given post-partum in reducing perinatal transmission.3

- · Observational studies (such as data from existing PEP programs).49

Studies of specific populations

- In an updated series of studies of PEP initiation in men having sex with men, seroconversion was low and seemed mostly related to either HIV risk factors that continued after completing PEP or not taking PEP medication as prescribed.4

- Studies of children and adolescents evaluated after sexual assault reported that among 672 children or adolescents offered PEP, 472 were known to have initiated the regimen, and 126 were reported to have completed a 28-day PEP course. No new HIV infections were documented among the 472 patients who initiated PEP.4

- In 15 studies conducted in mixed populations, 2,209 participants completed 28 days of PEP, and at least 19 individuals were found to have HIV. However, only one case of HIV was attributed to PEP failure. The other 18 cases were attributed, variously, to HIV risk factors that continued after the end of PEP, not taking PEP medication as prescribed, and starting PEP more than 72 hours after exposure.4

CDC has comprehensive guidelines for prescribing PEP

CDC's Updated Guidelines for Antiretroviral Postexposure Prophylaxis After Sexual, Injection Drug Use, or Other Nonoccupational Exposure to HIV—United States, 2016 provides guidance for how to prescribe antiretroviral medications for PEP, as well as evidence about the effectiveness of PEP from animal studies and human observational studies.

These guidelines also include considerations and resources for specific groups, such as pregnant patients, victims of sexual assault (including children), and patients without health insurance, as well as a suggested procedure for transitioning patients between PEP and HIV PrEP as appropriate.4

Special considerations for prescribing PEP

Pregnancy

Pregnancy has been shown to increase the chances of getting HIV through sex. Therefore, PEP can be an especially important method to protect pregnant people from getting HIV. If the person exposed to HIV is pregnant, seek expert consultation. In general, PEP is indicated at any time during pregnancy when a significant exposure has occurred, despite a possible risk to the pregnant patient and the fetus. The recommended PEP regimen remains the same.

Kidney impairment

In people with impaired kidney function and estimated creatinine clearance that is <50 mL/min, the dose of F/TDF used for PEP must be adjusted.

Additional information and special considerations when prescribing PEP are provided in CDC's Updated PEP Guidelines.

Supporting patients on PEP

Connect patients with resources to pay for PEP

In many states, PEP is covered by insurance, including Medicaid. If your patient is not covered under insurance, you can help them access assistance programs run by various manufacturers.

Assist your patients to pay for PEP by applying for assistance with the medication co-pay if the patient is insured; or applying for complete coverage of the medication if the patient does not have insurance or needs financial assistance. Note that the paperwork must be signed and submitted by a licensed clinical provider.

The Partnership for Prescription Assistance can also help qualified patients get the prescriptions they need at a very low cost.

Provide ongoing support to patients on PEP

Stay in touch with your patients on PEP, either by telephone or clinic visits, for the entire duration of their treatment. This helps to support patients taking their PEP medication as prescribed and facilitate follow-up HIV testing at 30 and 90 days.

Additionally, for people who get HCV and HIV at the same time, it might take longer for HIV tests to detect HIV.

Counsel patients on PEP to take steps to reduce the chances of transmitting HIV during the 12-week follow-up period. These steps include using condoms consistently, avoiding pregnancy or breast/chestfeeding, not sharing needles, and not donating blood, plasma, organs, tissue, or sperm.

Resources

Expert consultation services

Materials for you and your practice

Materials for your patients

- Tsai CC, Follis KE, Sabo A, et al. Prevention of SIV infection in macaques by (R)-9-(2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl) adenine. Science. 1995;270(5239):1197-1199. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/ science.270.5239.1197

- Otten RA, Smith DK, Adams DR, et al. Efficacy of postexposure prophylaxis after intravaginal exposure of pig-tailed macaques to a human-derived retrovirus (human immunodeficiency virus type 2). J Virol. 2000;74(20):9771-9775. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC112413/

- Wade NA, Birkhead GS, Warren BL, et al. Abbreviated regimens of zidovudine prophylaxis and perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(20):1409-1414. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199811123392001

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV—United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/programresources/cdc-hiv-nPEP-guidelines.pdf

- Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ, Gelman M, Grasso C. Raltegravir, tenofovir DF, and emtricitabine for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV: safety, tolerability, and adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(4):354-359. https://journals.lww.com/jaids/FullText/2012/04010/Raltegravir,_Tenofovir_DF,_and_Emtricitabine_for.6.aspx

- McAllister J, Read P, McNulty A, Tong WW, Ingersoll A, Carr A. Raltegravir-emtricitabine-tenofovir as HIV non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men: safety, tolerability and adherence. HIV Med. 2014;15(1):13-22. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/hiv.12075

- Chacko L, Ford N, Sbaiti M, Siddiqui R. Adherence to HIV post-exposure prophylaxis in victims of sexual assault: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(5):335-341. https://sti.bmj.com/content/88/5/335

- Cardo DM, Culver DH, Ciesielski CA, et al. A case-control study of HIV seroconversion in health care workers after percutaneous exposure. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Needlestick Surveillance Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-1490. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejm199711203372101

- Schechter M, do Lago RF, Mendelsohn AB, et al. Praca Onze Study Team. Behavioral impact, acceptability, and HIV incidence among homosexual men with access to post-exposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2004;35(15):519-525. https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2004/04150/Is_post_exposure_prophylaxis_affordable_.00010.aspx