At a glance

- Blastomycosis is an endemic community-acquired pneumonia in some parts of the U.S.

- It is often misdiagnosed, or diagnosis is delayed.

- While it only causes symptoms in about 50% of people, those with weakened immune systems can develop severe illness, including meningitis.

- Early diagnosis and prescription antifungals can prevent or treat serious infections.

Etiology

Blastomycosis is caused by the dimorphic fungus Blastomyces. Most blastomycosis infections in the United States are caused by B. dermatitidis or B. gilchristii. Recent infections in the western United States have been attributed to a newly described species, B. helicus.

Reservoir and endemic areas

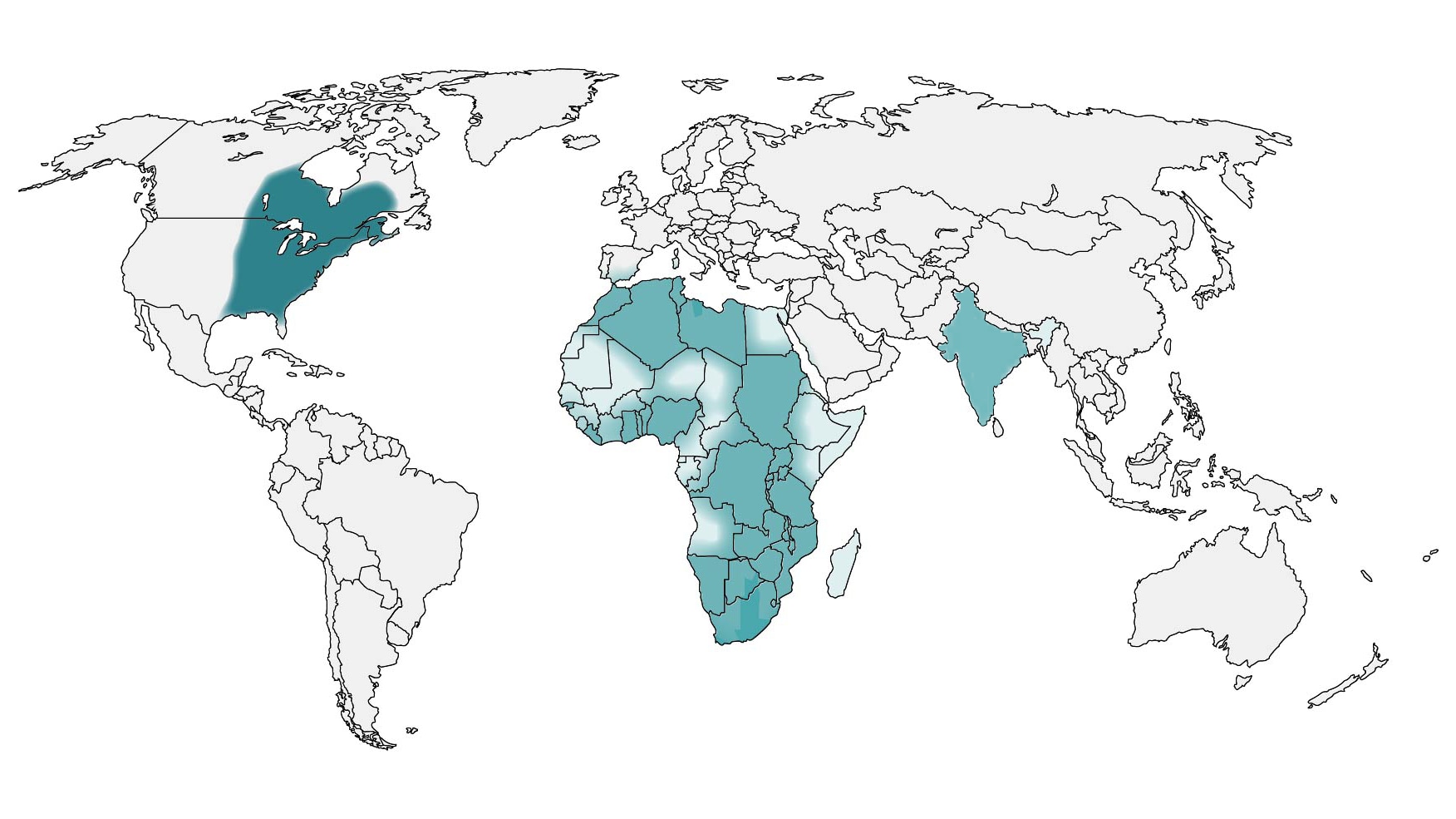

The fungus lives in the environment, most often in soil and decaying organic matter such as wood or leaves. It is endemic in the midwestern, south-central, and southeastern states. It is notably more common around the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes, Saint Lawrence River. Northern Wisconsin and Minnesota may be hyperendemic.

Parts of Canada are also endemic, particularly Ontario, Saskatchewan, Quebec, and Manitoba. Locally acquired cases have also been reported from Africa and India.

Risk factors

In endemic areas, activities that disturb soil or plant matter, like construction, excavations, and some outdoor activities, increase risk. According to a 2019 report, some racial and ethnic groups had higher incidence of blastomycosis. Populations included American Indian and Alaska Natives, Asians, Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders had the highest reported incidence.

People with weakened immune systems are at higher risk for developing severe forms of the disease.

How it spreads

Blastomycosis is typically acquired when people inhale airborne conidia from the environment. Blastomycosis skin infections are uncommon, and result from traumatic inoculation. It does not spread between people.

Clinical features

About 1-in-2 people who are infected with blastomycosis are asymptomatic. Symptoms can start from 3 weeks to 3 months after exposure among people who are infected. The clinical presentation of blastomycosis is often non-specific, but symptoms may include:

- Fever

- Cough

- Night sweats

- Muscle and joint pain

- Chest pain

- Fatigue

- Skin lesions

Acute pulmonary blastomycosis is the most common form of blastomycosis. It can progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome. Some symptomatic cases will develop extrapulmonary infection, which typically manifests as cutaneous, osteoarticular, genitourinary, or central nervous system disease.

Diagnosis

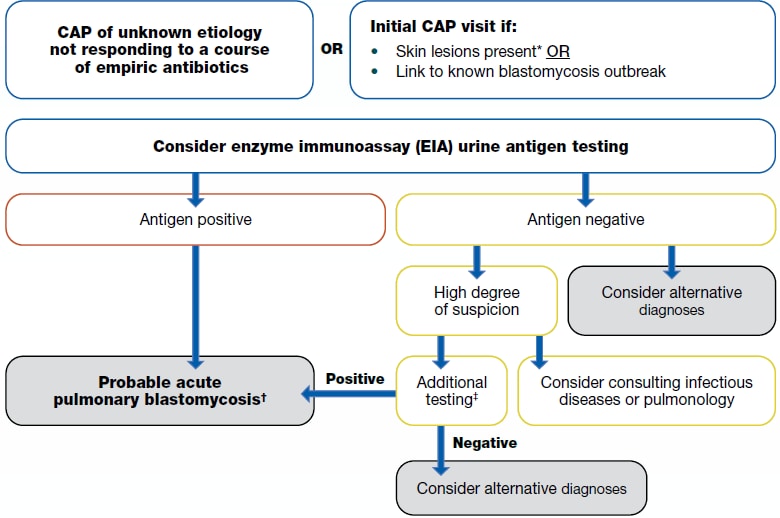

Testing Algorithm for Blastomycosis

- Antigen detection: Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is typically performed on urine or serum but can also be used on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. EIA urine antigen tests may have the highest sensitivity of noninvasive tests and the quickest turnaround time.

- Antibody tests: Antibody tests such as immunodiffusion and complement fixation are available but have low sensitivity and specificity. Antibody EIAs have also been developed and have better sensitivity and specificity but can be difficult to interpret. Antibody tests may be a useful adjunct diagnostic test when an antigen test is negative or when trying to differentiate blastomycosis from histoplasmosis, e.g., if done in combination with Histoplasma antibody testing.

- Culture: Culture is the gold standard for diagnosing blastomycosis. A commercially available DNA probe can be used to confirm. Sensitivity can be low.

- Microscopy: Microscopy is important for detection of yeast in tissue or respiratory secretions.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): Blastomyces PCR can be used to confirm culture or histopathologic identification and on blood to detect disseminated disease.

Treatment and recovery

Amphotericin B is recommended for moderate to severe disease, including that of the central nervous system. Itraconazole is recommended for mild to moderate disease and step-down therapy. For more detailed treatment guidelines, please refer to the Infectious Diseases Society of America's Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Blastomycosis.

Surveillance and statistics

Blastomycosis is reportable in certain states. Check with your state, local, or territorial health department about disease reporting requirements and procedures in your area.

- Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, Kumar UN, Mathai G, Varkey B, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986 Feb 27;314(9):529-34.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010 Apr;23(2):367-81.

- Baumgardner DJ, Halsmer SE, Egan G. Symptoms of pulmonary blastomycosis: northern Wisconsin, United States. Wilderness Environ Med. 2004 Winter;15(4):250-6.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, Bradsher RW, Pappas PG, Threlkeld MG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Jun 15;46(12):1801-12.

- Brown EM, McTaggart LR, Zhang SX, Low DE, Stevens DA, Richardson SE. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a cryptic species Blastomyces gilchristii, sp. nov. within the human pathogenic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59237.

- Schwartz IS, Wiederhold NP, Hanson KE, Patterson TF, Sigler L. Blastomyces helicus, a new dimorphic fungus causing fatal pulmonary and systemic disease in humans and animals in Western Canada and the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Jan 7; 68(2):188-195.

- Furcolow ML, Busey JF, Menges RW, Chick EW. Prevalence and incidence studies of human and canine blastomycosis. II. Yearly incidence studies in three selected states, 1960–1967. Am J Epidemiol. 1970;92(2):121–31.

- Tat J, Nadarajah J, Kus JV. Blastomycosis. CMAJ. 2023 Jul 31;195(29):E984.

- Cheikh Rouhou S, Racil H, Ismail O, Trabelsi S, Zarrouk M, Chaouch N, et al. Pulmonary blastomycosis: a case from Africa. ScientificWorldJournal. 2008 Nov 2;8:1098-103.

- Chakrabarti A, Slavin MA. Endemic fungal infections in the Asia-Pacific region. Med Mycol. 2011 May;49(4):337-44.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002 May 15;34(10):E44-9.

- Pappas PG, Threlkeld MG, Bedsole GD, Cleveland KO, Gelfand MS, Dismukes WE. Blastomycosis in immunocompromised patients. Medicine. 1993 Sep;72(5):311-25.

- Smith DJ, Williams SL, Endemic Mycoses State Partners Group, Benedict KM, Jackson BR, Toda M. Surveillance for Coccidioidomycosis, Histoplasmosis, and Blastomycosis — United States, 2019. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022;71(No. SS-7):1–14.