Key points

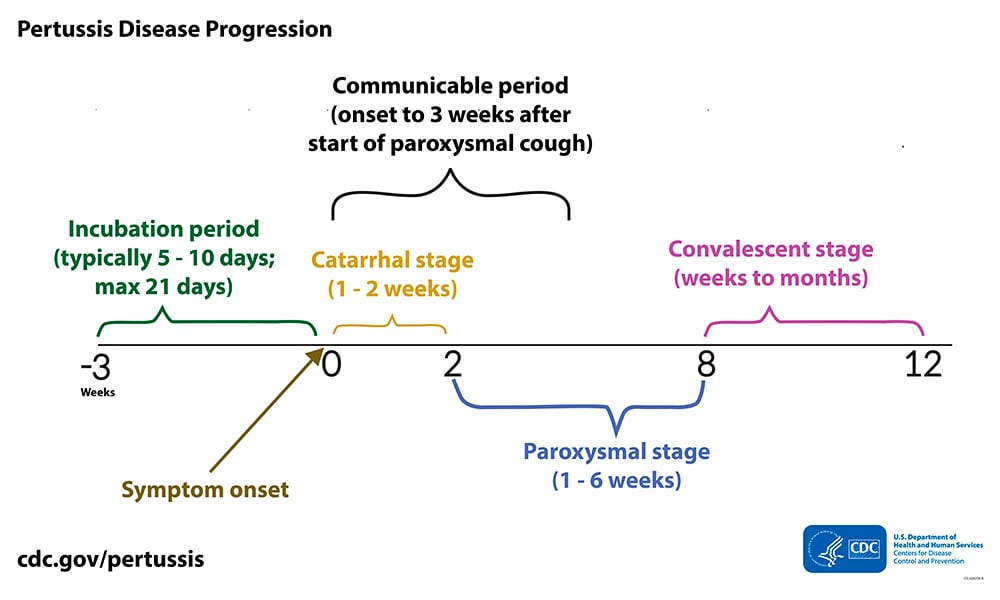

- There are three stages of clinical pertussis: catarrhal, paroxysmal, and convalescent.

- Clinical presentation, complications, and risk of death can differ based on age and vaccination status.

Stages to the clinical course

Stage 1: Catarrhal

Characterized by:

- Coryza

- Low-grade fever

- Mild, occasional cough

- Gradually becomes more severe

- Apnea (in infants)

Stage 2: Paroxysmal

Characterized by:

- Paroxysms of numerous, rapid coughs

- Long inspiratory effort with a high-pitched "whoop" at the end of paroxysmal cough

- Cyanosis

- Exhaustion

- Vomiting

Paroxysmal attacks occur frequently at night, with an average of 15 attacks per 24 hours. They increase in frequency during the first 1 to 2 weeks. The attacks remain at the same frequency for 2 to 3 weeks, then gradually decrease.

Stage 3: Convalescent

Characterized by:

- Gradual recovery

- Less persistent, paroxysmal coughs that disappear in 2 to 3 weeks

Paroxysms often recur with subsequent respiratory infections for many months after pertussis onset.

Differences in clinical presentation

Age

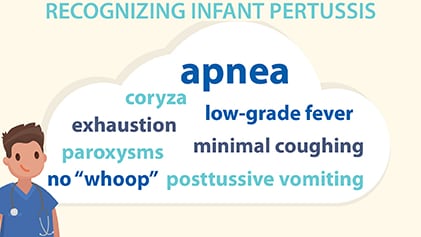

In infants, apnea may be the only symptom and the cough may be minimal or absent.

Healthcare providers often overlook pertussis in the differential diagnosis of cough illness in adolescents and adults. Illness is generally less severe, and the typical "whoop" less frequently seen in these populations.

Vaccination status

The illness can be milder and the characteristic paroxysmal cough and "whoop" may be absent in anyone who was previously vaccinated.

Complications

Pertussis complications can include:

- Anorexia

- Dehydration

- Difficulty sleeping

- Epistaxis

- Hernias

- Otitis media

- Syncope

- Weight loss

- Urinary incontinence

More severe complications can include:

- Apnea

- Encephalopathy (due to hypoxia from coughing or from toxin)

- Death

- Pneumonia

- Pneumothorax

- Rectal prolapse

- Refractory pulmonary hypertension (in infants)

- Rib fractures from severe coughing

- Seizures/convulsions

- Subdural hematomas

Infants

In infants younger than 12 months of age who get pertussis, about a third need treatment in a hospital. Hospitalization is most common in infants younger than 6 months of age.

Pertussis can also be more severe for infants under 2 months of age if their mother didn't receive Tdap during pregnancy.

Unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated infants younger than 12 months of age have the highest risk for severe complications and death.

The most common complications in this age group are apnea (68%) and pneumonia (22%).1

Adolescents and adults

Adolescents and adults can also develop complications from pertussis. However, complications are usually less severe in these older age group, especially in those who received pertussis vaccines.

Resources

Red Book

Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases textbook

Does this coughing adolescent or adult patient have pertussis?

2010 JAMA article

- National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, 2004–2014. Division of Integrated Surveillance Systems and Services, National Center for Public Health Informatics, Coordinating Center for Health Information and Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA 30333.

- Cortese MM, Bisgard KM. Pertussis. In: Wallace RB, Kohatsu N, Kast JM, ed. Maxcy-Rosenau-Last Public Health & Preventive Medicine, Fifteenth Edition. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2008:111–4.

- Tanaka M, Vitek CR, Pascual FB, Bisgard KM, Tate JE, Murphy TV. Trends in pertussis among infants in the United States, 1980-1999. JAMA. 2003;290:2968–75.