Key points

- Mycetoma is a chronic, progressive subcutaneous skin infection that can be caused by bacteria or fungi.

- Laboratory testing is required for diagnosis.

- Antibiotics or antifungals are used for treatment, depending on the cause of infection.

- If untreated it can spread deep into tissues or bone and can lead to disability.

- Amputation may be necessary in severe cases.

Overview

Mycetoma is a rare implantation infection, caused by any of several different types of fungi and bacteria, that causes progressively debilitating yet painless subcutaneous tumor-like lesions, usually on the extremities. It primarily affects low-income agrarian populations in tropical regions. Endemic areas are collectively called the Mycetoma Belt and include Venezuela, Chad, Ethiopia, India, Mauritania, Mexico, Senegal, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen.1

Mycetoma is caused by any or several of a diverse group of microorganisms. The predominant etiologic agent varies by geographic region. Fungal mycetoma (eumycetoma) and bacterial mycetoma (actinomycetoma) cause disease in Africa and Asia, while bacterial mycetoma (actinomycetoma) causes the majority of cases in South and Central America.2

Little is known about the global burden of mycetoma, transmission modes, risk factors, or pathogenesis. A retrospective review identified 19,494 cases published from 1876 to 2019, with cases reported in 102 countries.[2] In 2016, the World Health Organization added mycetoma to the list of neglected tropical diseases, an important step toward better epidemiologic characterization of the disease and concerted efforts to improve diagnostics and treatment and to establish prevention recommendations.3, 4

World Health Organization (WHO) Course

Clinical features

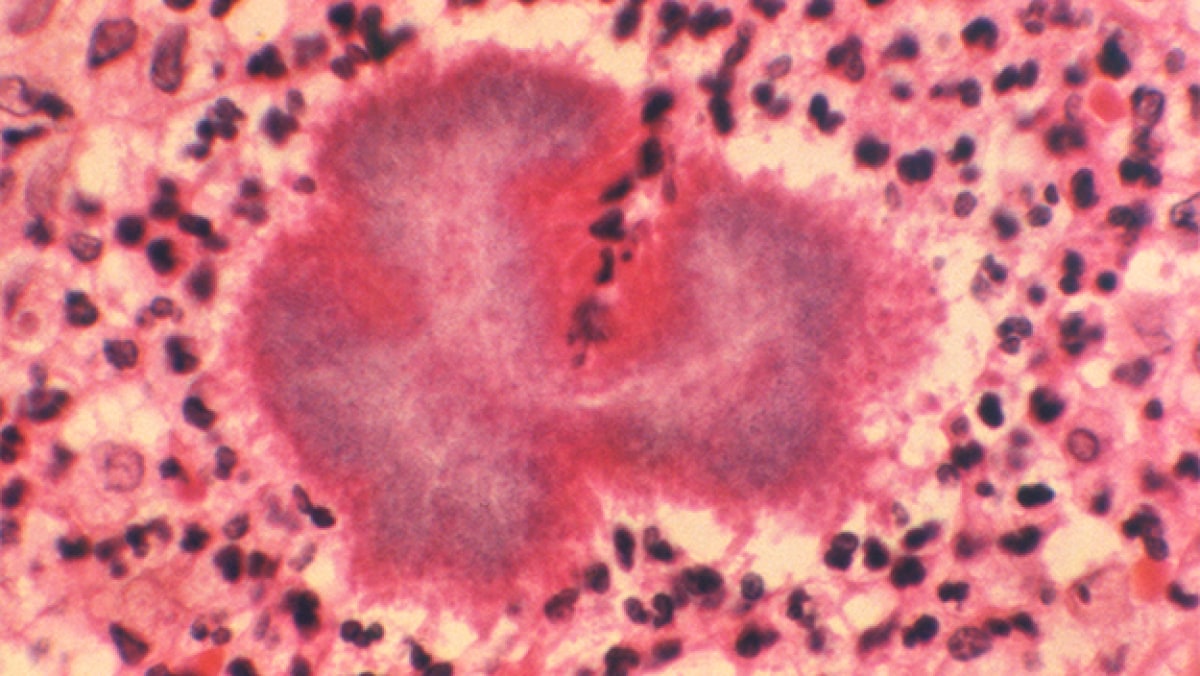

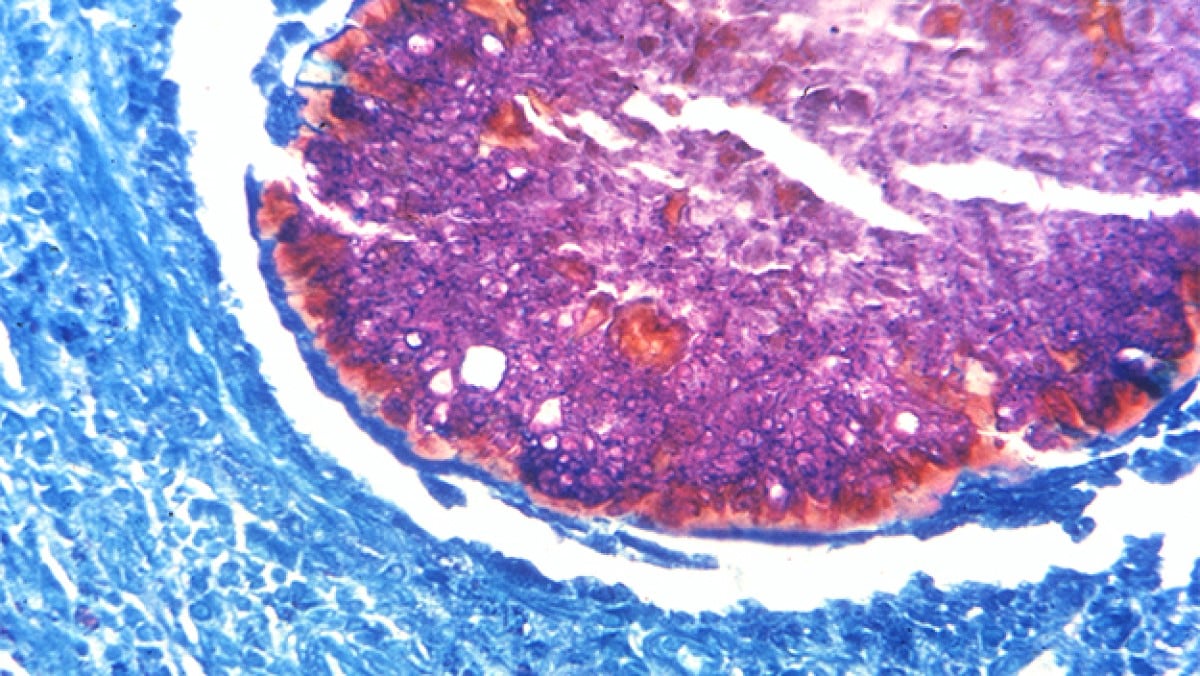

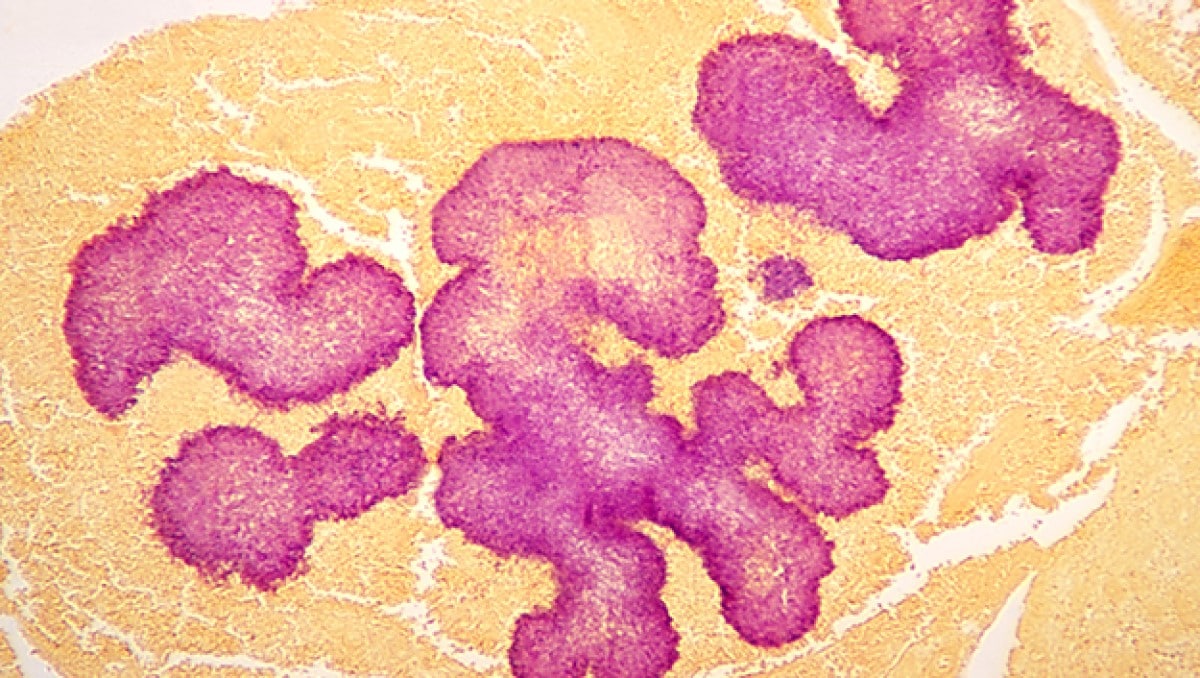

Mycetoma is a chronic granulomatous disease with a progressive inflammatory reaction. Over the course of years, mycetoma progresses from small nodules to large, bone-invasive mutilating lesions. Mycetoma is usually caused when skin is repetitively broken and exposed to soil or water that contains the causal bacteria or fungi.3 Mycetoma presents as a triad of painless, firm subcutaneous masses, formation of multiple sinuses within the mass, and a purulent or seropurulent discharge containing sand-like particles called "grains," that can be white, yellow, red, brown, or black. Because lesions are usually painless in early disease and slowly progressive, time from initial infection to initiation of care varies from months to years.5

Eumycetoma and actinomycetoma present virtually identically, although actinomycetomas progress to bone invasion more rapidly than eumycetomas. Actinomycetomas also occur more frequently on the chest, abdomen, and head compared with eumycetoma, which occurs primarily on the extremities.3 Secondary bacterial infection may be seen in mycetoma as well, further complicating treatment, and can lead to pain, disability, and fatal septicemia if untreated.

Photo by Dr. Ahmed Fahal, Mycetoma Research Center, Khartoum, Sudan

Prevention

Recommendations for prevention are based on avoidance of percutaneous inoculation of the infecting organism, believed by healthcare providers and researchers to be the most likely route of infection. Wearing closed-toed shoes and clothing that can protect from percutaneous injury are thought to be preventive.11 In addition, cleaning and disinfecting of skin wounds—should they occur in locations where mycetoma is seen—may also be preventive.12

Diagnosis

Proper treatment requires an accurate diagnosis that distinguishes actinomycetoma from eumycetoma. Culturing of grains obtained from deep lesion aspirates enables identification of the causal organism. Histopathology of deep biopsy specimens (deep swab or punch biopsy) stained with haematoxylin and eosin can diagnose actinomycetoma and eumycetoma. However, species identification cannot be made without culture. Molecular tests for certain causative organisms of mycetoma have been developed but are not readily available in endemic countries. Currently, no serologic tests can reliably diagnose mycetoma.

In endemic areas, healthcare providers use ultrasound to distinguish mycetoma from other subcutaneous lesions. Radiology is also used, and in one study, radiology correctly identified 97% of 516 patients who were diagnosed by clinical exam and histopathology,6 suggesting that radiology can be helpful in evaluating the extent of disease as well as response to treatment in patients with laboratory evidence of mycetoma. In a recent study of 758 patients with suspected mycetoma skin lesions in rural Sudan, clinical evaluation and ultrasound helped identify evidence of mycetoma in 220 (29%) patients. Among these, all had surgical excision or amputation with biopsy and histopathological exam, which confirmed mycetoma in 192 (87%) patients.7 CT and MRI may also be used, with MRI being the preferred method.8

Treatment and recovery

Treatment depends on identification of the causal organism and requires long-term and expensive drug regimens.9 Actinomycetoma generally responds to medical treatment, and surgery is rarely needed. Current first-line treatment is with co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) alone or in combination with a penicillin, dapsone, or an aminoglycoside. Cure rates can be as high as 90%.[9, 11, 14]

Eumycetoma is less responsive to medical therapies, and recurrence is common. Current recommended therapy is itraconazole for 9-12 months, but cure rates as low as 26% have been reported, and fungi can often still be cultured from lesions post-treatment.10 Surgical excision is often used with itraconazole to obtain better treatment outcomes. Amputation may be required if the combination of antifungals and surgical excision fails. Fosravuconazole is being investigated as a potentially more effective antifungal treatment.[13]

- van de Sande WW, Fahal A, Ahmed SA, Serrano JA, Bonifaz A, Zijlstra E. Closing the mycetoma knowledge gap. Med Mycol. 2017

- van de Sande WW. Global burden of human mycetoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2013 Nov;7(11):e2550.

- Zijlstra EE, van de Sande WW, Welsh O, Mahgoub el S, Goodfellow M, Fahal AH. Mycetoma: a unique neglected tropical disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Jan;16(1):100-12.

- World Health Organization: Mycetoma

- Fahal AH, Hassan MA. Mycetoma. Br J Surg. 1992 Nov;79(11):1138-41.

- Abd El-Bagi ME, Fahal AH. Mycetoma revisited. Incidence of various radiographic signs. Saudi Med J. 2009 Apr;30(4):529-33.

- akhiet SM, Fahal AH, Musa AM, Mohamed ESW, Omer RF, Ahmed EG, et al. A holistic approach to the mycetoma management. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018 May

- Czechowski J, Nork M, Haas D, Lestringant G, Ekelund L. MR and other imaging methods in the investigation of mycetomas. Acta Radiol. 2001 Jan;42(1):24-6.

- Estrada-Castañon R, Estrada-Chávez G, de Guadalupe Chávez-Lopez M. Diagnosis and management of fungal Neglected Tropical Diseases in community settings—mycetoma and sporotrichosis. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019 Jun

- Zijlstra EE, van de Sande WW, Fahal AH. Mycetoma: A Long Journey from Neglect. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2016 Jan;10(1):e0004244.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E, Salinas MC. Actinomycetoma and advances in its treatment. Clinics in dermatology. 2012 Jul-Aug;30(4):372-81.

- Zein HA, Fahal AH, Mahgoub el S, El Hassan TA, Abdel-Rahman ME. Predictors of cure, amputation and follow-up dropout among patients with mycetoma seen at the Mycetoma Research Centre, University of Khartoum, Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012 Nov;106(11):639-44.

- Nenoff P, van de Sande WW, Fahal AH, Reinel D, Schofer H. Eumycetoma and actinomycetoma–an update on causative agents, epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnostics and therapy. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2015 Oct;29(10):1873-83.

- Tomczyk S, Deribe K, Brooker SJ, Clark H, Rafique K, Knopp S, et al. Association between footwear use and neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2014;8(11):e3285.