Key points

- Having a family health history of a birth defect, developmental disability, newborn screening disorder, or genetic condition makes you more likely to have a baby with this condition.

- Talk to your healthcare provider if you have concerns about your or your partner's family health history.

Overview

Planning for pregnancy

Thinking about having a baby? If you have a family health history that includes a birth defect, developmental disability, newborn screening disorder, or genetic condition, you might be more likely to have a baby with this condition. Learning more about your family health history before you get pregnant can give you time to address any concerns. Remember to consider the family health history of both potential parents, not just mom. Be sure to discuss any concerns with your healthcare provider. Testing before you get pregnant can give you time to think about what the results mean for you and consider all your options. In some cases, results might impact your pregnancy planning.

During pregnancy

Expecting a baby? You might be wondering whether your baby will have mommy's eyes or daddy's dimples. But your baby will inherit much more than that. Learn about both parents' family health history to give your baby the best start possible. If either of you has a family health history of a birth defect, developmental disability, newborn screening disorder, or genetic condition, your baby might be more likely to have this condition. Knowing if your baby is more likely to have one of these conditions is important so that you can find and address potential health problems early. Your healthcare provider might recommend genetic counseling and genetic testing or other testing based on your or your partner's family health history.

Reasons for genetic counseling

Based on your family health history, your healthcare provider might refer you for genetic counseling. Other reasons for genetic counseling include having had

- Infertility (trouble getting pregnant),

- 2 or more miscarriages,

- A previous pregnancy or child with a genetic condition or birth defect, or

- A baby who died at less than 1 year of age.

After genetic counseling, you might decide to have genetic testing for conditions that could affect your baby. If a genetic disorder runs in your family and the genetic change that causes the disorder is known, make sure that you are tested for that genetic change.

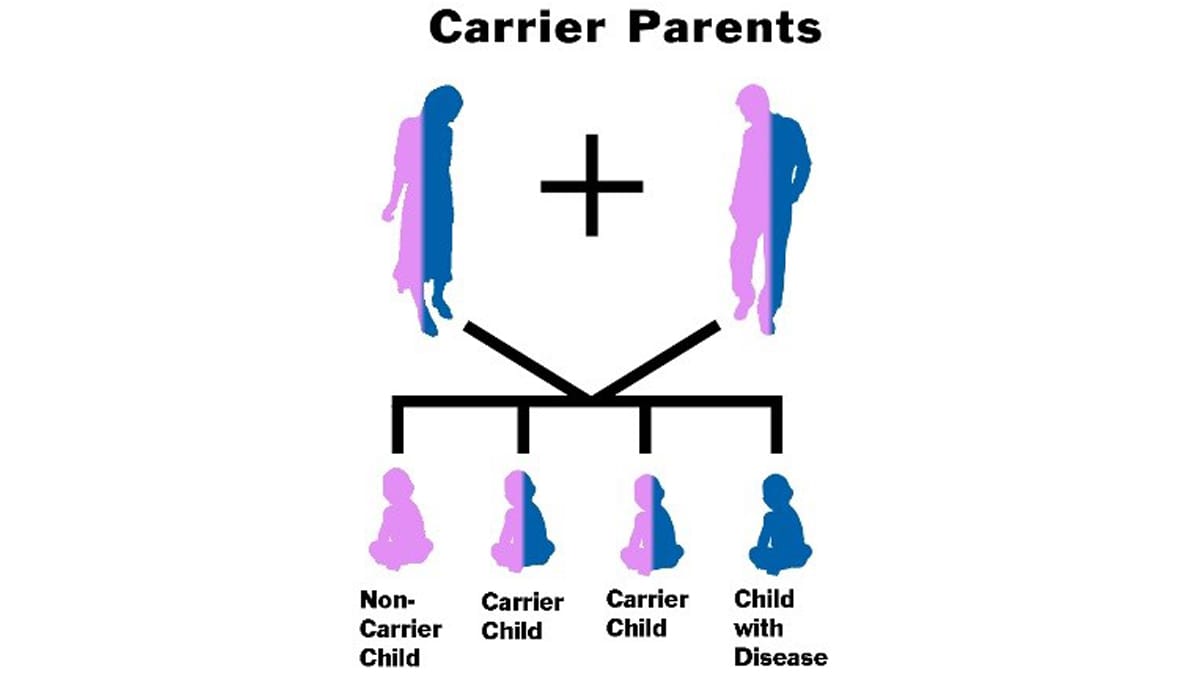

How carrier screening works

Parents can have a baby with a genetic condition even though neither parent has it. Babies inherit two copies of each gene, one from each parent. For some genetic conditions, the baby will only have the condition if both copies of the gene related to the condition do not work properly. In cases like these, each parent has one copy of the gene that works properly and one that does not. If the baby inherits both non-working copies of the gene, the baby has the condition. Thus, the parents are "carriers" for the condition, meaning that they don't have the condition themselves but can have children with it.

Your healthcare provider might ask if you want to have screening, called carrier screening, to check if you are a carrier for certain common genetic conditions. If one of these genetic conditions runs in your family, you might need different testing than the carrier screening offered to most women. Current recommendations1 state that

- All women should be offered carrier screening for cystic fibrosis and spinal muscular atrophy.

- All women should be checked for hemoglobinopathies (blood disorders that affect red blood cells) such as sickle cell disease and thalassemia.

- Women with a family health history of fragile X syndrome or intellectual disability suggestive of fragile X syndrome should be offered testing to see if they could have a child with fragile X.

- If either partner is of Ashkenazi, Eastern European, or Central European Jewish descent, that person should be offered carrier screening for genetic conditions that are more common in this population, such as Canavan disease. If both have this ancestry, only one partner needs to be tested to start.

- If either partner is of Ashkenazi, Eastern European, or Central European Jewish; French-Canadian; or Cajun descent, that person should be offered screening for Tay-Sachs disease. If both have this ancestry, only one partner needs to be tested to start.

- When possible, carrier screening should be done before pregnancy.

If the results show that you are a carrier for a genetic condition, be sure to share this information with your family members. Your partner will also need to have carrier screening to know if you could have a baby with the condition.

Collecting family health history

- Gather family health history information before seeing your healthcare provider.

- Collect family health history using the online tool, My Family Health Portrait.

- Tell your healthcare provider if you have any family members with a genetic condition, chromosomal abnormality, developmental disability, birth defect, newborn screening disorder, or other problem at birth or during infancy or childhood, especially if you have had a previous pregnancy or child affected by one of these conditions.

- Talk to affected family members or their caregivers, if possible, to find out their specific diagnoses. Ask for a copy of their genetic or diagnostic test results, if any, to share with your healthcare provider.

- Alert your healthcare provider if you have had a previous preterm birth, miscarriage, stillbirth, or a child who died from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Follow your healthcare provider's recommendations. For example, if you have had a previous pregnancy or child affected by spina bifida or anencephaly, your healthcare provider might recommend that you take a higher than normal dose of the B vitamin, folic acid, before and during pregnancy.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 691: Carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):e41-e55.