American Trypanosomiasis

[Trypanosoma cruzi]

Causal Agent

Trypanosoma cruzi, is a parasitic protozoan that is the causative agent of Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). Currently, six distinct lineages of T. cruzi are classified into discrete typing units (TcI-VI), which vary in their geographic occurrence, host specificity, and pathogenicity.

Life Cycle

. Inside the host, the trypomastigotes invade cells near the site of inoculation, where they differentiate into intracellular amastigotes

. Inside the host, the trypomastigotes invade cells near the site of inoculation, where they differentiate into intracellular amastigotes  . The amastigotes multiply by binary fission

. The amastigotes multiply by binary fission  and differentiate into trypomastigotes, and then are released into the circulation as bloodstream trypomastigotes

and differentiate into trypomastigotes, and then are released into the circulation as bloodstream trypomastigotes  . Trypomastigotes infect cells from a variety of tissues and transform into intracellular amastigotes in new infection sites. Clinical manifestations can result from this infective cycle. The bloodstream trypomastigotes do not replicate (different from the African trypanosomes). Replication resumes only when the parasites enter another cell or are ingested by another vector. The “kissing” bug becomes infected by feeding on human or animal blood that contains circulating parasites

. Trypomastigotes infect cells from a variety of tissues and transform into intracellular amastigotes in new infection sites. Clinical manifestations can result from this infective cycle. The bloodstream trypomastigotes do not replicate (different from the African trypanosomes). Replication resumes only when the parasites enter another cell or are ingested by another vector. The “kissing” bug becomes infected by feeding on human or animal blood that contains circulating parasites  . The ingested trypomastigotes transform into epimastigotes in the vector’s midgut

. The ingested trypomastigotes transform into epimastigotes in the vector’s midgut  . The parasites multiply and differentiate in the midgut

. The parasites multiply and differentiate in the midgut  and differentiate into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes in the hindgut

and differentiate into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes in the hindgut  . Other less common routes of transmission include blood transfusions, organ transplantation, transplacental transmission, and foodborne transmission (via food/drink contaminated with the vector and/or its feces).

. Other less common routes of transmission include blood transfusions, organ transplantation, transplacental transmission, and foodborne transmission (via food/drink contaminated with the vector and/or its feces).Hosts/Vectors

Apart from humans, a number of mammals serve as reservoir hosts for T. cruzi, e.g. armadillos, opossums, raccoons, woodrats, some other rodents, and domestic dogs. Common triatomine vector species for trypanosomiasis belong to the genera Triatoma, Rhodnius, and Panstrongylus.

Geographic Distribution

T. cruzi is endemic in vectors and wildlife reservoirs throughout the Americas from the southern half of the United States down to Argentina. Chagas disease cases have been reported from South and Central American countries, particularly in rural, impoverished areas. There have been a small number of autochthonous cases of Chagas disease in the United States.

Clinical Presentation

Chagas disease has an acute phase and chronic phase. The acute phase is usually asymptomatic, but can present with nonspecific somatic symptoms. Rarely, the acute phase may be more severe with potential cardiac or neurologic symptoms and signs. Nodular lesions or furuncles, usually called chagomas, may develop around the vector’s feeding site. Chagomas occurring on the on the eyelids are commonly referred to as palpebral and periocular firm swelling. Most acute cases resolve over a period of a few weeks or months into a subclinical chronic form of the disease (“indeterminate form”). Reactivation of Chagas disease from this asymptomatic form may occur in patients with HIV or those receiving immunosuppressive drugs.

The symptomatic chronic form (“determinate form”) may not occur for years or even decades after initial infection. This may include cardiac or gastrointestinal involvement, which occasionally occur together. The many complications of chronic Chagas disease can be fatal. Amastigote invasion of smooth muscle can lead to megaesophagus, megacolon, and dilated cardiomyopathy.

Trypanosoma cruzi in thick blood smears stained with Giemsa.

T. cruzi in thin blood smears stained with Giemsa.

T. cruzi in thin blood smears stained with Giemsa.

T. cruzi in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) stained with Giemsa.

T. cruzi amastigotes in heart tissue.

T. cruzi epimastigotes, from culture.

Triatomine bug, the T. cruzi vector.

Trypanosoma cruzi is transmitted by kissing bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). The most common genera responsible for transmission of the disease are Triatoma, Rhodnius, and Panstrongylus. Infection usually occurs after bugs defecate on the bite site and are rubbed into the wound by the host scratching.

Morphology

In the acute stage of the disease, diagnosis may be made by the finding of trypomastigotes in circulating blood or cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). During the chronic stage, trypomastigotes are usually not found circulating in blood and serologic testing is recommended (see below). Amastigotes may be found in biopsy specimens stained with hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) or Giemsa.

Serology (Antibody Detection)

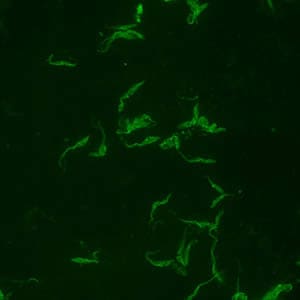

Positive IFA result with T. cruzi antigen (magnification 400x).

During the acute phase of illness, blood film examination generally reveals the presence of trypomastigotes. However, during the chronic phase of infection, parasitemia is low and immunodiagnosis is a useful technique for determining whether the patient is infected.

Diagnosis of chronic Chagas disease in suspected patients is based on serology performed with at least two different serologic tests. CDC utilizes an FDA-cleared enzyme immunoassay (EIA) based on recombinant T. cruzi antigens alongside an immunoblot (TESA) as the two first-line tests. If initial EIA and TESA results are discordant, a second specimen is requested and testing is repeated. If results of the second EIA and TESA are discordant, an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) is used as a “tie-breaker” test. Various serologic methods are commercially available in other countries for laboratory diagnosis of Chagas disease. The sensitivity and specificity of these tests are highly variable.

Molecular Testing

Molecular diagnosis of Chagas disease is performed for cases of suspected acute infection (including transfusion or transplant transmission), congenital Chagas disease, and for monitoring of suspected laboratory exposures. For chronic Chagas disease, serology is generally most appropriate, although molecular detection may be performed for re-activated cases associated with immunosuppression.

At CDC molecular detection of T. cruzi DNA is performed using a combination of two real-time PCR assays (TCZ and MNC). Acceptable specimen types are EDTA blood (minimum of 2.2 ml), heart biopsy tissue (in saline or paraffin-embedded) and, in cases of suspected central nervous system involvement, CSF.

References:

Bern C, Montgomery SP, Herwaldt B L, Marin-Neto JA, Dantas RO, Maguire JH, Acquatella H, Morillo C, Kirchhoff LV, Gilman RH, Reyes, PA, Salvatella R, Moore AC. Evaluation and Treatment of Chagas Disease in the United States. Aa Systematic Review. JAMA 2007 298 2171-81

Diez M, Favaloro L, Bertolotti A, Burgos JM, Vigliano C, Lastra MP, Levin MJ, Arnedo A, Nagel C, Schijman AG, Favaloro RR. Usefulness of PCR Strategies For Early Diagnosis of Chagas’ Disease Reactivation and Treatment Follow-Up in Heart Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2007; 7: 1633–1640.

Afonso AM, Ebell MH, Tarleton RL. A systematic review of high quality diagnostic tests for Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012; 6(11):e1881.

Qvarnstrom Y, Schijman AG, Veron V, Aznar C, Steurer F, da Silva AJ. Sensitive and specific detection of Trypanosoma cruzi DNA in clinical specimens using a multi-target real-time PCR approach. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012; 6: e1689.

Laboratory Safety

Standard safety protocols for handling blood and sharps (https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticprocedures/blood/safety.html). The risk of needle-sticks should be seriously mitigated with all possible precautions; several symptomatic cases of laboratory-acquired T. cruzi infections following needles-ticks are known.

Suggested Readings

Bern, C., Kjos, S., Yabsley, M.J. and Montgomery, S.P., 2011. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas’ disease in the United States. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 24 (4), pp.655-681.

Pérez-Molina, J.A., Molina, I. 2018. Chagas disease. The Lancet, 391 (10115), pp.82-94.Treatment Information

DPDx is an educational resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention, control, and treatment visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.