What to know

- Disasters are stressful events that can affect how your child may react.

- After a disaster, children may develop mental health symptoms like anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Learn what steps you can take to help your children cope with traumatic events.

Why it's important

Disasters are stressful events that can cause significant harm to communities and families. After a disaster, children may develop symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Mental health plays an important role in physical health, school performance, behavior, and long-term quality of life. It is important to keep children physically and mentally safe before, during, and after a disaster.

An emergency can happen anywhere and at any time. It is important for parents to know what steps they can take to protect their family. Ensure that family members are ready and know what to do when emergencies happen.

Children are at risk for mental health issues

Emotional stress from a disaster can be harder on children because they:

- Understand less about the situation.

- Feel less able to control events.

- Have less experience dealing with stressful situations.

- May not be able to communicate their feelings, such as fear or anxiety.

Children who have previously experienced trauma or have pre-existing mental health conditions can be more vulnerable before a disaster occurs. For example, children with autism, infants, and toddlers may find it hard to communicate their thoughts and feelings. Parents and caregivers can take steps to help their children cope with traumatic events.

Before an emergency

A little preparation now can make a big difference later.

Here are some steps you can take to help keep your family safe and healthy when an emergency happens.

Make a plan

- Discuss plans for emergencies with your children.

- This can include making emergency action plans together.

- This can include making emergency action plans together.

- Make a plan to contact family members, especially if you are not together when an emergency strikes.

- Create a plan to reunite with family members as soon it is safe to do so.

- Children may be away from their parents or accidentally separated during an emergency.

- If family members cannot return to their home, having an alternative meeting location, such as a community center, can help them reunite after a disaster.

- Children may be away from their parents or accidentally separated during an emergency.

Prepare and practice

- Include your children in making emergency supply kits that include:

- A three-day supply of necessities (food, water, medicine) for each person in your family.

- Supplies such as a flashlight, games, and special toys to help keep your children calm during an emergency.

- A three-day supply of necessities (food, water, medicine) for each person in your family.

- If your children are old enough, teach them how to call 911 and memorize important phone numbers.

- Review the different types of emergencies that can happen in your area with your children.

- Review warning signs for emergencies. For example, if tornadoes are common, your children should know what to do during a tornado. This includes

- Knowing the signs of an approaching storm.

- Knowing how to take shelter during a tornado.

- Knowing the signs of an approaching storm.

- Be informed, stay informed, and get important information such as emergency warnings and alerts. Use reliable news sources and your local emergency management agency.

Tip

Contact your school

Help protect your child during the school day.

In the United States, about 69 million children are separated from their parents or caregivers every work day to attend school or child care. You can help protect your children even when you are not with them.

Every school and child care center should have a written emergency plan. This can include information such as how to contact parents in an emergency and where children will go if they evacuate.

- Find out the school or child care center's emergency plans.

- Ask how you can contact the school or child care center during an emergency.

- Ask how parents and caregivers will reunite with their children.

- Ask how you can contact the school or child care center during an emergency.

- Talk to school administrators and safety officials about safety drills.

- Learn about safety drills taking place in your child's school or early care and education (ECE) facility.

- Talk with your child’s teacher or ECE professionals about how to help your child see safety drills as empowering instead of scary.

- Since drills vary by state, you can also look on your state's Department of Education web page.

- Learn about safety drills taking place in your child's school or early care and education (ECE) facility.

- Update your emergency contact information.

- Make sure that the school has up-to-date emergency contact information for your child.

- Let the school know as soon as possible if your address or phone number changes.

- Put an emergency card in your child's backpack. This is one way to make sure information such as emergency contact, medications, and allergies is readily available.

- Make sure that the school has up-to-date emergency contact information for your child.

During an emergency

Different emergencies may require different actions. Protect your family by knowing what to do.

Every emergency is different. You may need to take different actions to keep yourself and your family safe. Look for safety instructions and updates from local authorities on:

- Television.

- Radio.

- Internet.

- Social media (Twitter, Facebook, or other platforms).

If your children are with you, you can:

- Stay calm and reassure your children.

- Talk to your children about what is happening. Keep it simple and talk to them in a way that they can understand.

If your children are at school

Depending on the emergency, authorities may ask you to stay where you are ("shelter in place") or they may recommend that you go somewhere else ("evacuate").

If you have children attending school in the affected area, school authorities may evacuate your children to a safer place. In these cases, do not go to your children during the emergency. This can put you and your children at greater risk of danger. Wait until the emergency or school authorities say it is safe for you to pick up your children.

Information on specific emergencies

After an emergency

Recovery can take time. Get the support you need to help you and your child in the after an emergency.

- You can help your children feel a sense of control. Manage their feelings by encouraging them to take action directly related to the disaster.

- Children can help others after a disaster, including volunteer to help community or family members in a safe environment. Children should NOT participate in disaster cleanup activities for health and safety reasons.

- Allow your child to be with you or another trusted adult. Help your child feel safe and calm and give them a sense of hope. Children can handle disruption better when they know it is temporary.

How children may react

Children at any age may feel upset or have other strong emotions after an emergency. Some children react right away, while others may show signs of difficulty much later. Knowing how to help children cope after an emergency can help them stay healthy in future emergencies.

Common reactions to distress will fade over time for most children. However, children who were directly exposed to a disaster can become upset again. Their behavior related to the event may also return if they see or hear reminders of what happened. Children may have different reactions or show common signs of distress at different ages.

Infant to 2 years old

- May become more cranky.

- Cries more than usual.

- Wants to be held and cuddled more.

3 to 6 years old

- May return to behaviors they have outgrown. For example:

- Toilet accidents.

- Bed-wetting.

- Scared about being separated from their parents/caregivers.

- Toilet accidents.

- Has tantrums or is frustrated.

- Shows unusual disobedience.

- Has trouble sleeping.

- Stays away from others.

- Has less interest in playing.

7 to 10 years old

- May feel sad or mad.

- May be afraid that the event will happen again.

- Has anxiety about going back to school.

- May learn false information from peers. However, parents or caregivers can correct the misinformation.

- Focuses on details of the event and wants to talk about it all the time.

- Does not want to talk about the event at all.

- Has trouble concentrating on tasks.

- Has trouble sleeping.

Preteens and teenagers

- May respond to trauma by acting out. This could include:

- Reckless driving.

- Alcohol use.

- Drug use.

- Reckless driving.

- May be scared to leave home.

- Spends less time with their friends.

- Shows increased anxiety and depression.

- Is overwhelmed by their intense emotions and feels unable to talk about them.

- Argues and/or fights more with siblings, parents/caregivers or other adults.

- Has trouble sleeping or is sleeping too much.

Special needs children

- Children who need continuous use of a breathing machine, those who use a wheelchair, or those who are confined to a bed may have stronger reactions to a threatened or actual disaster.

- They might have more intense distress, worry, or anger than children without special needs because they have less control over day-to-day well-being than other people.

- The same is true for children with other physical, emotional, or intellectual limitations.

- May need extra words of reassurance.

- May need more explanations about the event.

- May need more comfort and positive physical contact, such as hugs from loved ones.

If children continue to be very upset or if their reactions hurt their schoolwork or relationships, parents may want to talk to a professional. They may also want to have their children talk to someone who specializes in children's emotional needs.

Helping children cope

Setting a good example for your children is critical for parents and caregivers. Manage your stress through healthy lifestyle choices. This can include:

- Eating healthy.

- Exercising regularly.

- Getting plenty of sleep.

- Not taking drugs.

- Not drinking alcohol.

When you are prepared, rested, and relaxed, you can respond better to unexpected events. You can also make decisions in the best interest of your family and loved ones.

Ask how they feel

- Give your child opportunities to talk about what they went through. Ask them what they think about the experience.

- Encourage your child to share concerns and ask questions.

- Answer your child's questions in a truthful and understandable way. You can also correct any misinformation about the event.

Recreate normal routines

- Return to your normal daily routine and encourage your child to do the same. Eating meals as a family or returning to school and work can help reduce stress.

- If your child's routines and environment get disrupted, talk about the changes. Explain what you are doing to create routines and structures.

- If you or other caregivers are not able to provide the same consistent care as before, talk to your child about how long it will last.

Be mindful of what they see

- Limit your child's exposure to media coverage of the disaster and its outcome. Children who were directly exposed to a disaster can become upset again if they see or hear reminders of what happened.

- Talk with school or child care teachers about how your child is coping in different situations.

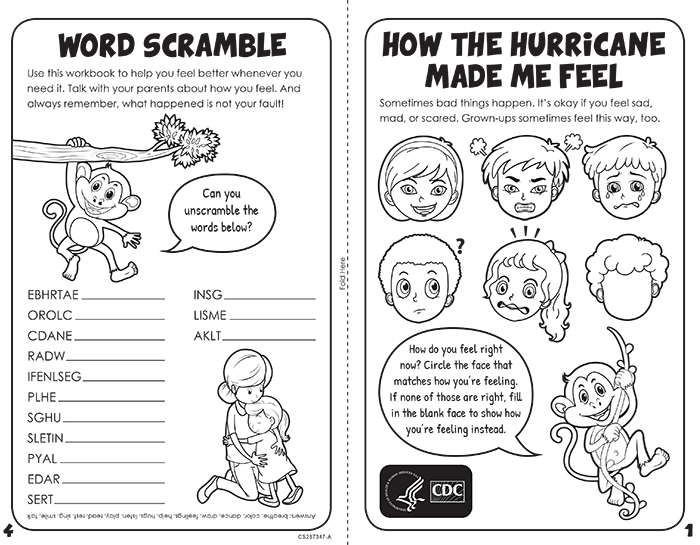

Download and print the activity sheet

Get help from a professional

Children and teenagers may have different but common emotional and behavioral reactions immediately after a disaster. Consider talking to a professional (for example, pediatrician, school counselor, child psychologist, or someone who specializes in children’s emotional needs) if:

- Your child continues to be anxious, fearful, sad, or angry for more than two to four weeks after the disaster.

- Your child's problems get worse over time instead of getting better.

- Your child's reactions affect their behavior in early care and education settings, their schoolwork, or their relationships with friends or family for a prolonged period.

Spotlight

People who are deaf or hard of hearing can use their preferred relay service to call 1-800-985-5990.

Resources

Coping with a disaster

- American Red Cross: Recovering After a Disaster or Emergency

- Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration: Disaster Technical Assistance Center

- National Institute of Mental Health: Coping with Traumatic Events

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network

- Practice Parameter on Disaster Preparedness

- Federal Emergency Management Agency: Coping with Disasters

Children's mental health

- How are Children Different from Adults?

- Children's Mental Health

- Mental Health

- Coping with a Disaster or Traumatic Event

- Helping Teens Cope After a Natural Disaster

- After a Crisis: Helping Young Children Heal

- Helping Children and Adolescents Cope with Violence and Disasters: What Parents Can Do (Spanish version)

- Children In Disasters: Teachers and Early Care and Education Programs

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

- The National Academies Press: Tools for Supporting Emotional Wellbeing in Children and Youth

- Cain SD, Plummer CA, Fisher RM, Bankston TQ. Weathering the Storm: Persistent Effects and Psychological First Aid with Children Displaced by Hurricane Katrina. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2010;3:330-343.

- Abramson DM, Redlener IE, Stehling-Ariza T, Sury B, Banister AN, Park YS (2010). Impact on Children and Families of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill: Preliminary Findings of the Coastal Population Impact Study (https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac:128195)

- Abramson D, Stehling-Ariza T, Garfield R, Redlener I. Prevalence and Predictors of Mental Health Distress Post-Katrina: Findings from the Gulf Coast Child and Family Health Study. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2:77-86.

- Furr JM, Comer JS, Edmunds JM, Kendall PC. Disasters and Youth: A Meta-Analytic Examination of Posttraumatic Stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:765-780.

- Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, Ali MM, Lynch SE, Bitsko RH, et al. Prevalence and Treatment of Depression, Anxiety, and Conduct Problems in US Children. J Pediatr. 2019;206:256-267.

- Hafstad GS, Haavind H, Jensen TK. Parenting After a Natural Disaster: A Qualitative Study of Norwegian Families Surviving the 2004 Tsunami in Southeast Asia. J Child Fam Stud. 2012;21:293-302.

- Marsee MA. Reactive Aggression and Posttraumatic Stress in Adolescents Affected by Hurricane Katrina. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:519-529.

- NCCD. 2010 Report to the President and Congress: (https://archive.ahrq.gov/prep/nccdreport/nccdreport.pdf [1.15 MB / 192 pages])

- Pfefferbaum B, Jacobs AK, Houston JB, Griffin N. Children's Disaster Reactions: The Influence of Family and Social Factors. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17:57.

- Powell T, Thomspon SJ (2014). Enhancing Coping and Supporting Protective Factors After a Disaster: Findings From a Quasi-Experimental Study. (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1049731514559422)

- Schonfeld DJ, Demaria T, Disaster Preparedness Advisory Council and Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Providing Psychosocial Support to Children and Families in the Aftermath of Disasters and Crises. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1120-e1130.

- Vasterman P, Yzermans CJ, Dirkzwager AJ. The Role of the Media and Media Hypes in the Aftermath of Disasters. Epidemiol Rev. 2005;27:107-114.