At a glance

As of October 21, 2024

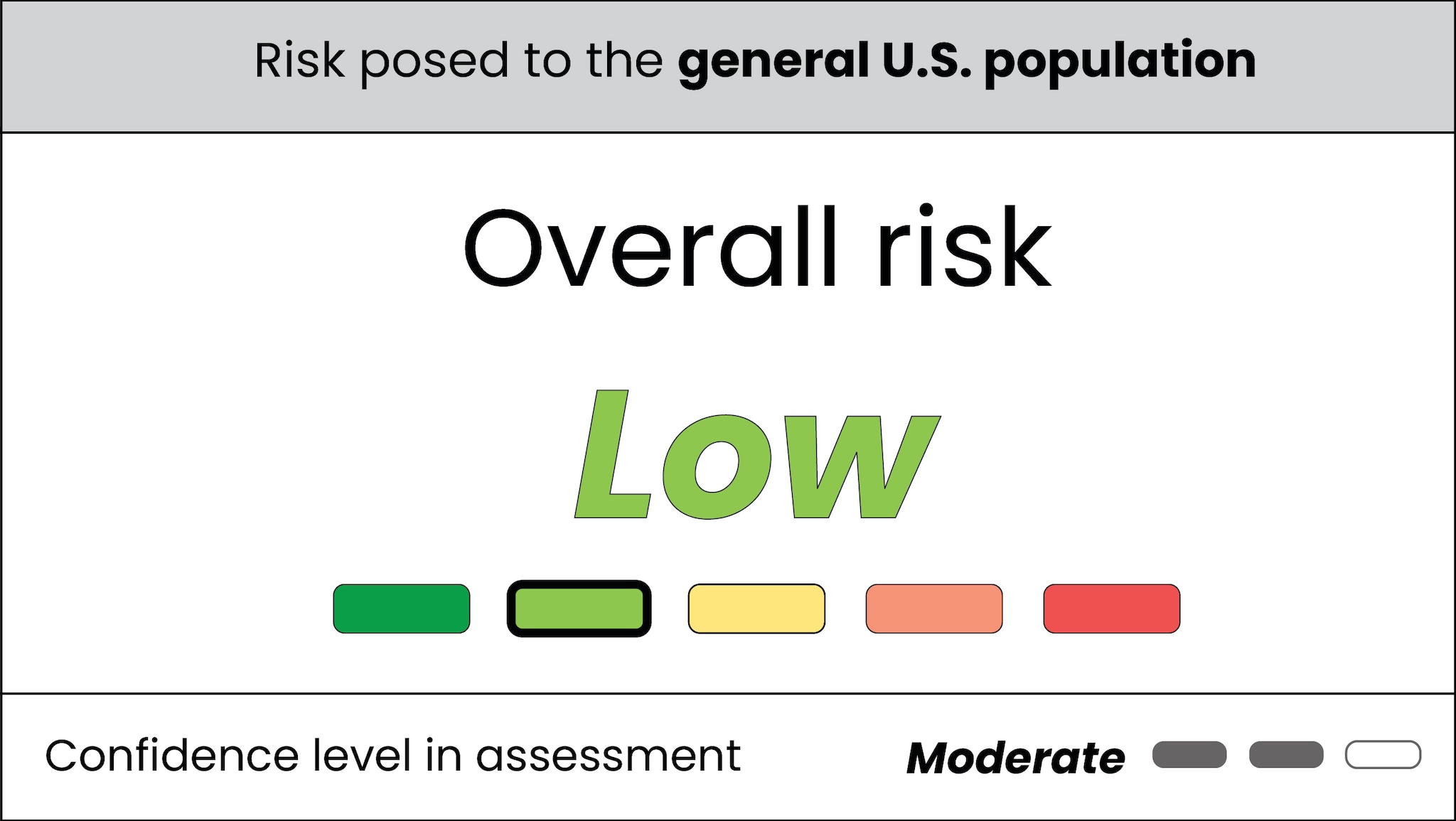

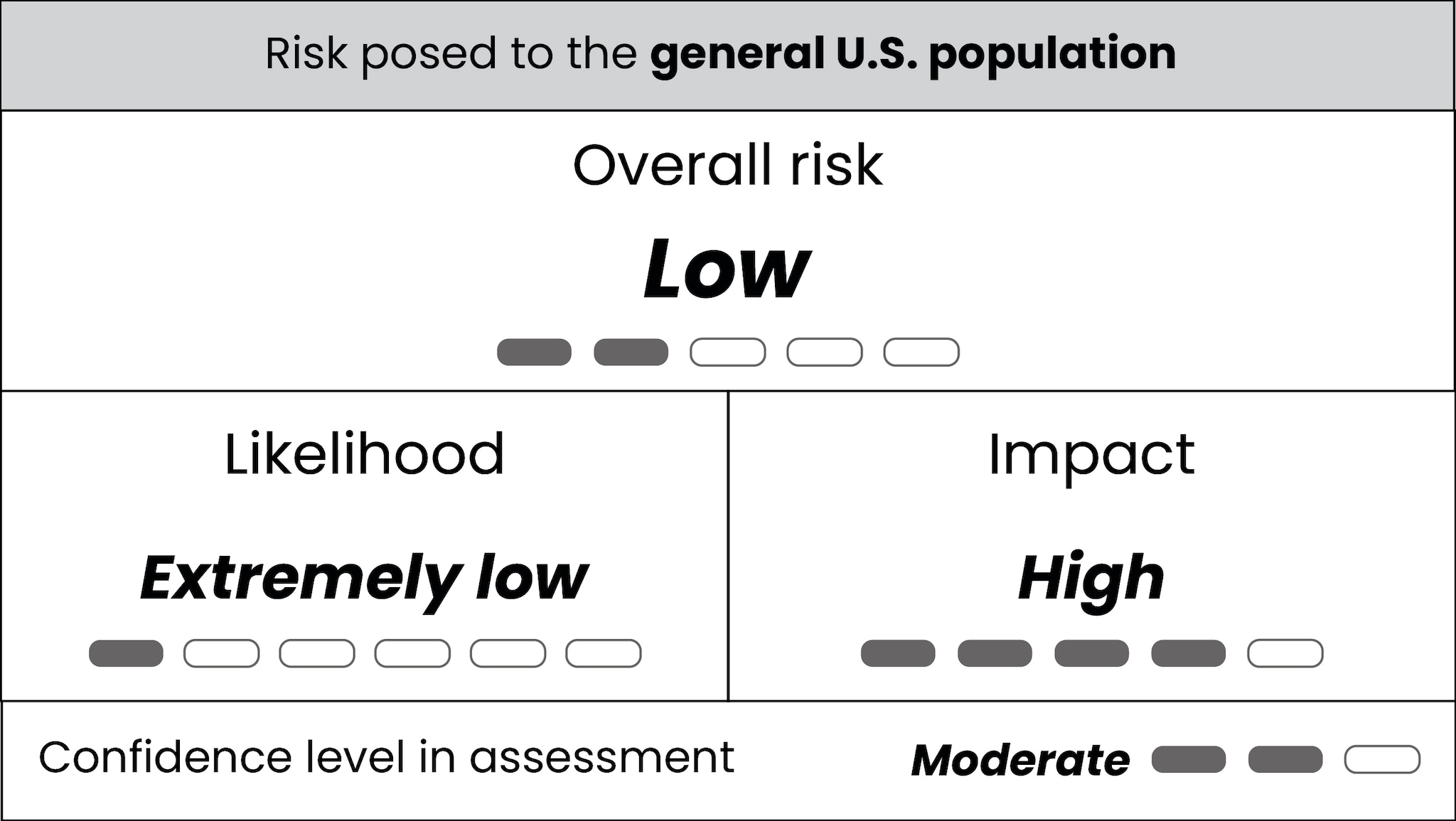

CDC assessed the risk posed by the Marburg virus outbreak in the Republic of Rwanda to the United States general population during the next three months. The risk to the general U.S. population is low, with moderate confidence.

The purpose of this assessment is to provide context about the outbreak of Marburg virus disease in Rwanda to inform U.S. preparedness efforts. The assessment relied on subject-matter experts evaluating a range of evidence related to risk, including epidemiologic data from the outbreak in Rwanda and historical data on Marburg virus epidemiology and clinical severity. We continue to monitor the situation and will update this risk assessment if new information warrants changes.

Risk assessment for the general population in the United States

Likelihood

The likelihood of Marburg infection for the general population is extremely low. Factors that informed our assessment of likelihood include the following:

- As of October 21, 2024, there is no evidence of community transmission in Kigali, Rwanda's capital. Epidemiological data indicate that transmission has been limited to three clusters of cases: one family-associated, and two hospital-associated. Rwandan health authorities have responded to the initial cases quickly. They are monitoring more than 700 contacts of cases and continue to investigate the timeline, transmission chains, and source of the outbreak.

- There are no known cases of Marburg virus disease in the United States. However, there remains a risk of potential spread from Rwanda to the United States through other countries, via travelers from Rwanda who may be infected.

- Broader spread of Marburg virus disease cases in Rwanda—especially in Kigali, where there are more travel links to other countries—and neighboring countries would increase the risk of importation to the United States. However, there are no direct commercial flights from Rwanda to the United States, and the daily number of passengers whose flights originate in Rwanda is low.

- CDC has posted online information and electronic messages in airports, and is sending text messages, to advise travelers arriving from Rwanda about the importance of rapidly and safely seeking care if they develop symptoms that could be related to Marburg. CDC is additionally conducting public health entry screening at designated U.S. airports to facilitate recommended post-arrival management of U.S.-based healthcare workers and other travelers arriving from Rwanda.

- Broader spread of Marburg virus disease cases in Rwanda—especially in Kigali, where there are more travel links to other countries—and neighboring countries would increase the risk of importation to the United States. However, there are no direct commercial flights from Rwanda to the United States, and the daily number of passengers whose flights originate in Rwanda is low.

- If Marburg virus is introduced to the United States through a traveler, we expect there could be limited spread before control measures are implemented, as symptoms can appear suddenly and may be non-specific.

- While there is no approved vaccine to prevent infection, the United States has a high capacity for implementing case identification, isolation, contact tracing, and infection prevention and control measures that are likely to stop an outbreak before it grows significantly. These measures are likely to be effective in part because the average interval between subsequent cases is long (9 days) and transmission is unlikely to occur before symptoms appear.

- For example, Ebola virus, a related pathogen, resulted in no community spread and only two infections in healthcare workers in the United States following two introductions and seven medical evacuations from other countries to the U.S. in 2014-2015.

- While there is no approved vaccine to prevent infection, the United States has a high capacity for implementing case identification, isolation, contact tracing, and infection prevention and control measures that are likely to stop an outbreak before it grows significantly. These measures are likely to be effective in part because the average interval between subsequent cases is long (9 days) and transmission is unlikely to occur before symptoms appear.

- Healthcare workers have been disproportionately affected in this outbreak in Rwanda; as of October 21, 2024, more than 80% of confirmed cases have been in healthcare workers. Infection is more likely in U.S. healthcare workers practicing in or recently returned from Rwanda than the general population. U.S. healthcare workers would also have an elevated chance of infection if a patient with unrecognized Marburg virus disease seeks care in the United States.

- Marburg virus is highly infectious, and some symptoms are non-specific, so U.S. healthcare workers practicing in Rwanda could acquire infection before Marburg virus disease is recognized and proper precautions taken.

- Marburg virus disease in this group could result in spread to close contacts if not detected immediately. For this reason, CDC has worked with state and local health jurisdictions to implement interim recommendations for public health management of U.S.-based healthcare workers returning from Rwanda, in order to help limit spread of the virus (see Background section).

- However, the risk of exposure among healthcare workers, including U.S. healthcare workers practicing in Rwanda, is likely to decrease as precautionary protocols are implemented in healthcare settings in Rwanda.

- Marburg virus is highly infectious, and some symptoms are non-specific, so U.S. healthcare workers practicing in Rwanda could acquire infection before Marburg virus disease is recognized and proper precautions taken.

Impact

The impact of infection for the general population would be high. Factors that informed the assessment of impact included the following:

- Marburg virus disease is a serious, deadly disease. In past outbreaks, between 20% to 90% of people infected with the disease died. However, many patients who died in past outbreaks were in locations that did not have access to the level of care that is available in U.S. intensive care units. Currently, treatment is limited to supportive care, including rest, hydration, managing oxygen status and blood pressure, and treatment of secondary infections.

- People in the United States do not have immunity to Marburg virus, and there are no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved treatments or vaccines currently available. However, experimental vaccines and treatments are available and could be utilized in limited scenarios, should the need arise and if appropriate FDA authorizations are approved.

- Even very limited Marburg virus spread in the United States could cause significant panic and fear among the public, and disruption to normal societal activities. In addition to the lives directly affected, Marburg virus spread would require significant public health resources, risk communication, and community engagement. Containment requires extensive contact tracing activities, long quarantine for persons with high-risk exposures (up to 21 days), and stringent barrier protection measures for healthcare workers and laboratory personnel.

Confidence

We have moderate confidence in this assessment.

We note uncertainty in the implications for the United States of the Marburg virus disease outbreak in Rwanda, including uncertainties related to limited visibility on the epidemiology of the current outbreak in Rwanda, and whether adequate measures are in place to limit transmission in the country and in the surrounding region. We also have uncertainties around affected districts in Rwanda and travel patterns between affected districts and other countries.

Factors that could change our assessment

- Detection of Marburg virus disease cases in the United States

- The outbreak in Rwanda intensifying or spreading to other countries, in the region or globally, raising the likelihood of imported cases in the United States

- Any evidence suggesting increased transmissibility compared to past outbreaks

- Any evidence of changed clinical severity compared to past outbreaks

- Successful clinical trials for vaccines and/or treatments

Background and Methods

On September 27, 2024, the Republic of Rwanda's Ministry of Health reported cases of Marburg virus disease in several districts, including in some patients and workers in healthcare facilities. Rwandan authorities identified cases reported from eight of the 30 districts in the country. However, epidemiological data of infected individuals was limited, and it was not clear whether reported districts were linked to where individuals live, or where their illness was reported. Additionally, several cases were not linked to known transmission chains, suggesting additional cases may have been undetected or unreported.

As of October 20, 2024, Rwanda has reported 62 illnesses and 15 deaths (case fatality rate: 24%) from Marburg virus disease. A vaccination campaign with a vaccine in phase II clinical trials began on October 5, targeting healthcare workers, and has reached more than 500 individuals. More than 80%of the people infected to date have been healthcare workers from two healthcare facilities in Kigali, Rwanda's capital city. Kigali has a population of 1.7 million and serves as a regional travel hub, with an international airport and road networks to several cities in East Africa. This is the first reported outbreak of Marburg virus disease in Rwanda. Rwanda's Ministry of Health has responded swiftly and has launched several initiatives to contain the outbreak, including a vaccination campaign, contact tracing, and exit screening at key locations in the country.

Marburg virus disease is a rare, severe viral hemorrhagic fever in the same viral family as Ebola virus. The Marburg virus is most commonly found in sub-Saharan Africa. The virus is found in Egyptian Rousette fruit bats and can spread from infected bats (through saliva, urine, and feces) to people. Once the disease has "spilled over" from wildlife to people, people who are sick can spread the disease to others (person-to-person). Infections are transmitted through direct contact with bodily fluids (through broken skin or mucous membranes in the eyes, nose, or mouth) or through contaminated objects (such as bedding or medical equipment).

People with Marburg virus disease usually start getting sick 5 to 10 days after infection (range of 2-21 days). Symptoms can appear suddenly and may include fever, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, and severe bleeding. There are no specific treatments or vaccines that are FDA-approved for Marburg virus, although candidate vaccines and treatments are under development.

Groups at higher risk of acquiring Marburg virus disease include:

- People caring for individuals sick with Marburg virus disease without proper protective equipment and procedures, including healthcare workers

- People in contact with Egyptian Rousette fruit bats or their excretions in enzootic countries

- People in contact with infected nonhuman primates in enzootic countries

Given the high percentage of healthcare workers infected with Marburg virus in Rwanda and concerns regarding infection prevention and control practices being used in healthcare facilities in Rwanda, CDC recommends at this time that U.S. healthcare personnel who have been present in a Rwandan healthcare facility be excluded from work duties in U.S. healthcare facilities until 21 days after their last presence in a healthcare facility in Rwanda. CDC has additional interim recommendations for public health management of U.S.-based healthcare workers returning from Rwanda, as well as other travelers from Rwanda.

CDC is supporting response efforts:

- CDC has deployed several scientists to assist Rwanda with its investigation and response to Marburg virus disease.

- CDC and its partners across Africa continue to work together to monitor disease, ensure local laboratories have adequate testing capacity, train local laboratory and public health staff, investigate illnesses, and advise on treatment practices and proper protection protocols for healthcare workers.

- CDC is raising awareness of the outbreak among healthcare providers in the United States, including providing the latest guidance on what to do if a patient is suspected of having Marburg virus disease.

CDC subject-matter experts specializing in risk assessment methods, infectious disease modeling, global health, and Marburg virus and other filoviruses collaborated to develop this rapid assessment. Experts initially convened in early October 2024 to discuss the need for an assessment examining the risks to the United States posed by the Marburg virus outbreak in Rwanda, key evidence related to this outbreak, and specific populations to include in the assessment. To conduct this assessment, experts considered evidence including epidemiologic data from the ongoing Marburg virus outbreak in Rwanda, and historical data on Marburg virus outbreaks in central and eastern Africa. Teams deployed to Rwanda helped to corroborate the data.

Risk was estimated by combining the likelihood of infection and the impact of the disease. For example, low likelihood of infection, combined with high impact of disease, would result in moderate risk. The likelihood of infection refers to the probability that members of the general U.S. population would acquire Marburg virus disease over the next three months, which in turn depends on the likelihood of exposure, infectiousness of the disease, and susceptibility of the population. The impact of infection considers several factors affecting the consequences of infection, including the severity of disease, level of population immunity, availability of treatments and vaccines, and necessary public health response resources. A degree of confidence was assigned to each level of the assessment, taking into account evidence quality, extent, and corroboration of information.

For more details on our methods, please see our rapid risk assessment methods webpage.