About

This ACIP GRADE handbook provides guidance to the ACIP workgroups on how to use the GRADE approach for assessing the certainty of evidence.

Summary

The GRADE approach is used to determine the certainty of evidence across the body of evidence for each outcome identified as critical or important for decision-making1. The certainty in the evidence reflects how confident we are that the observed effect reflects the true effect (Table 4).

The process of assessing the certainty of evidence begins by categorizing the study design into one of two groups:

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

- Non-randomized studies (NRS) - also known as observational studies, i.e., cohort studies, case control studies, controlled before-after studies, interrupted time series studies, and case series.

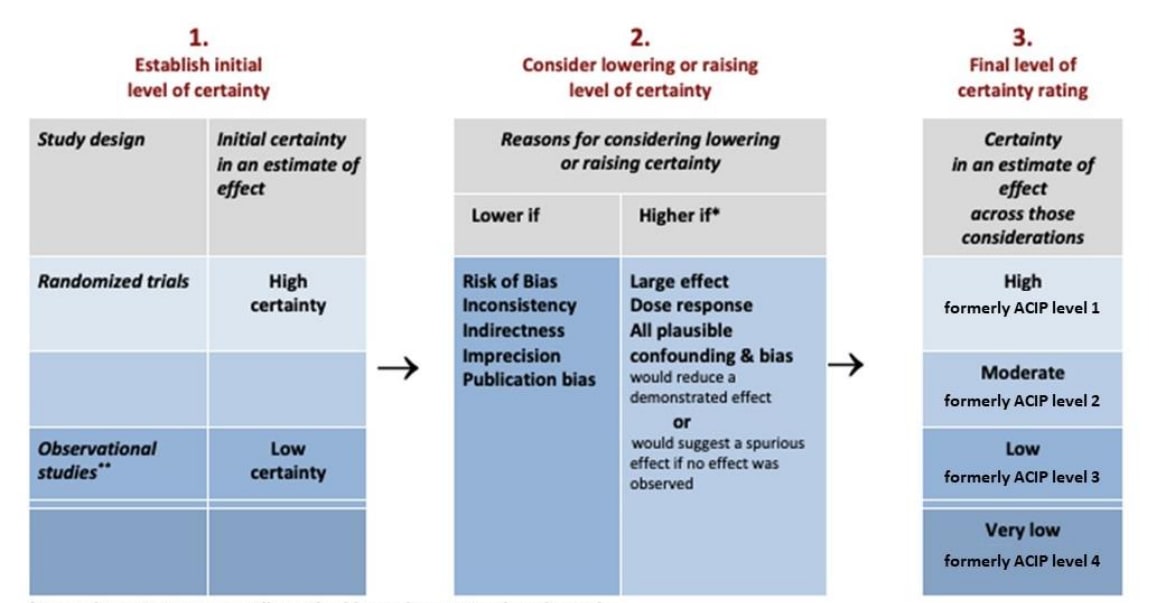

Randomized controlled trials initially start at a high level of certainty (former ACIP level 1) while non-randomized studies traditionally start at low level of certainty (former ACIP level 3) (Figure 5). This accounts for the lack of randomization in non-randomized studies, which increases the risk of residual or unknown confounding. However, if non-randomized studies are appropriately evaluated for risk of bias using a tool that assesses risk of bias along an absolute scale, such as the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool (currently available for comparative cohort studies), the evidence may start at an initial high certainty level2. The ROBINS-I tool assesses selection bias and confounding as an integral part of the evaluation process, unlike most other risk of bias tools for NRS2. The final certainty of evidence rating should not change based on the type of risk of bias instrument used. Five GRADE domains are used for downgrading the evidence type: risk of bias; inconsistency; indirectness; imprecision; and publication bias. Three GRADE criteria can be used to upgrade the evidence level of non-randomized studies: strength of association; dose-response; and opposing plausible residual confounding or bias. RCTs are typically not upgraded using these criteria as it risks erroneously inflating the certainty of the body of evidence.

Figure 5. GRADE criteria for assessing the type or certainty of evidence (adapted)

References in this figure: 3

*Upgrading criteria are usually applicable to observational studies only

**Observational studies start at Low certainty unless use an appropriate RoB instrument such as ROBINS-I

The final “ACIP Level” certainty rating can be interpreted as how confident the authors are in the results. Formerly, these were ranked numerically (1—4) but ACIP has replaced numbers with the terms “high”, “moderate”, “low”, “very low”. Since older publications of GRADE will use the numerical levels, the correlates appear here for posterity. Table 4 presents the current and formerly used numerical ACIP levels of certainty in the evidence and how they can be conceptualized.

Table 4. Conceptualizing the certainty of the evidence4

The final certainty of evidence for an outcome is cumulative of the considerations for rating down or rating up (non-randomized studies). For example, when the body of evidence from well-performed (i.e., no uncertainty or reason for rating down) NRS demonstrates both strength of association and dose response, the evidence type may be rated up by two levels from Low to High (i.e., formerly ACIP Level 1). Typically, if the body of evidence for an outcome is rated down due to concerns from one or more of the previously described domains, it would not be rated up as this may overstate the certainty of an estimate thought to be substantially different from the truth. For example, if there is serious concern with the risk of bias due to lack of blinding, which may overestimate the effect, this outcome should not be rated back up due to large magnitude of effect.

Reviewers should categorize the final evidence certainty by making judgements on the individual GRADE domains in the context of their identified strengths or limitations. GRADE recognizes that judgment is involved during the evidence assessment and that overall certainty reflects if and how much concerns about the domains matter. It should be noted that concerns about domains for rating down may not equate in a one-to-one relationship to the overall certainty. For example, limitations pertaining to the risk of bias (e.g., the pooled analysis includes studies at both high and low risk of bias) and indirectness domains are identified, but these limitations are not serious enough for moving down each of the domains, the overall evidence type may be downgraded by one level when limitations for both domains are considered together (e.g., downgrade from high to moderate). The GRADE domain that played the biggest role in downgrading as well as all contributing factors should be specified.

The PICO question must be considered when determining the study design classification for an outcome. For example, a study in which infants are randomized into two different vaccination schedules would be classified as an RCT if the question is about which vaccination schedule is more effective. However, it would be classified as an NRS with no control group if the comparison group consists of infants who do not receive vaccination. Therefore, study design judgements should not be based on how authors of a study describe their methodology, but should consider how the study methodology aligns to answer the PICO question. This can be presented in the GRADE evidence profiles in one of two ways: 1) Identify study design as "Randomized Trial" to match the published study methodology and rate down twice for risk of bias with a footnote delineating that the evidence used to inform the outcome broke randomization; or 2) Identify study design as "Observational Study" and include a footnote that delineates the details of the trial. The PICO question should not be rephrased to reflect the evidence identified.

After conducting the GRADE assessment, the evidence can be categorized as either high, moderate, low or very low (formerly within ACIP, the equivalent levels were 1 [High], 2 [Moderate], 3 [Low], and 4 [Very low]). The certainty of the evidence reflects the confidence in the effect estimates that help inform recommendations. For guidelines, it is important to note that while the certainty of the evidence helps inform the recommendation, there are other factors that inform judgements about the strength of a recommendation. These can be found in the ACIP Evidence to Recommendation User's Guide.5

- Guyatt, G.H., et al., GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011 Apr;64(4):395-400. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.012. Epub 2010 Dec 30. PMID: 21194891.

- Schünemann HJ, Cuello C, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019/07// 2019;111:105-114. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.01.012

- Morgan RL, Thayer KA, Bero L, et al. GRADE: Assessing the quality of evidence in environmental and occupational health. Environ Int. 2016/08//Jul- undefined 2016;92-93:611-616. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2016.01.004

- Schünemann HJ. Interpreting GRADE's levels of certainty or quality of the evidence: GRADE for statisticians, considering review information size or less emphasis on imprecision? J Clin Epidemiol. 2016/07// 2016;75:6-15. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.03.018

- ACIP Evidence to Recommendation User’s Guide (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (2020)