Key points

- Two CDC studies report that tackle football athletes sustained more head impacts than flag football athletes.

- Head impacts increase the risk for concussion and other serious head injuries.

Overview

A CDC study published in Sports Health found that youth tackle football athletes ages 6 to 14 sustained 15 times more head impacts than flag football athletes during a practice or game. Tackle football athletes also sustained 23 times more high-magnitude head impacts (hard head impacts) than flag football athletes during a practice or game.

Head impacts increase the risk for concussion and other serious head injuries.

Key findings from the study include:

- Youth tackle football athletes experienced a median of 378 head impacts per athlete during the season.

- Flag football athletes experienced a median of 8 eight head impacts per athlete during the season.

These findings suggest that non-contact or flag football programs may be a safer alternative for reducing head impacts and concussion risk for youth football athletes under age 14.

More efforts needed to prevent head impacts during youth football games

A second CDC study published in The American Journal of Sports Medicine reports youth tackle and flag football athletes sustained two times more head impacts during a game than during a practice.

Key findings from the study include:

- Youth tackle football athletes had an estimated 18 times more head impacts per practice and 19 times more head impacts per game than flag football athletes.

- Youth tackle football athletes had an average rate of almost 7 head impacts during a practice and 13 impacts during a game, resulting in 2 times more ≥10g head impacts in games versus practices (g is a measurement of gravitational force equivalent).

- Youth flag football athletes had an average rate of 0.4 head impacts during a practice and 0.8 impacts during a game, resulting in 2 times more ≥10g head impacts in games versus practices.

- Youth tackle football athletes sustained 2 times more high magnitude head impacts (≥40g) in games vs practices.

These findings suggest a greater focus on game-based interventions, such as fair play interventions and strict officiating. In addition, the expansion of non-contact or flag football programs may be beneficial to reduce head impact exposures—especially for youth football athletes.

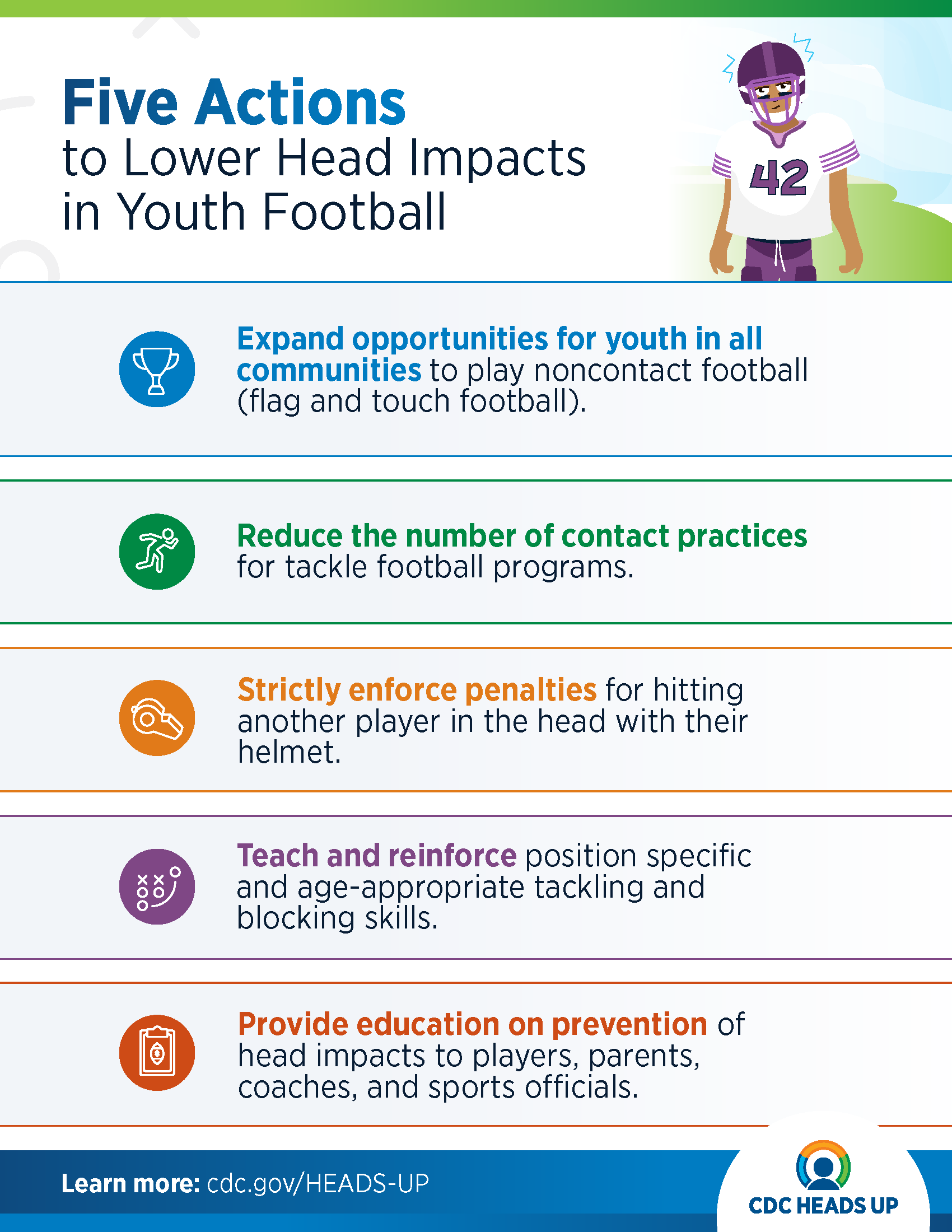

Five actions to lower head impacts in youth football

1. Expand opportunities for youth in all communities1 to participate in low-cost2 non-contact football programs, such as flag and touch football.

Why this is important: Non-contact football, like other sports, help youth build skills in athletics, leadership, and teamwork.3

2. Reduce the number of contact practicesA per week and the amount of time contact is allowed during a practice for tackle football programs.

Why this is important: Head impacts during the high school football season dropped by 42% when a school reduced contact practices from 3 or more days to 2 or fewer days per week.4

3. Strictly enforce penalties for hitting another player in the head with their helmet, such as spearing or targetingB for tackle football programs.

Why this is important: Strict officiating and enforcing rules by coaches and athletes can decrease rates of injuries.5678

4. Teach and reinforce position-specific910 and age-appropriate tackling and blocking skills11 that avoid using the head to hit another player when contact drills are used during tackle football practice.

Why this is important: Head impacts are more common among linemen12 and when players do high-speed,13 intensive14 and multiplayer tackle drills.1516

5. Provide education for players, parents, coaches, and sports officials on the:

- Dangers of head-first contact in football.

- Limits of protective equipment.

- Best techniques to avoid head impacts.

- Penalties for spearing, targeting, and hitting another player in the head.

- Importance of communication about brain safety between coaches, parents, athletes, and sports officials.

Why this is important: Training can improve identification and response to concussions and other head injuries.1718 Policies that require education combined with rule enforcement and contact practice restrictions may be most effective.19202122

Protecting players from head impacts lowers their chance for:

- Traumatic brain injuries (including concussions)2324

Head-first contactC and spearingD create the greatest forces to the head and risk for severe injury and disability.2528303132339

More information

What Parents Need to Know About Brain Safety and Youth Football

What Sports Programs Need to Know About Brain Safety and Youth Football

Additional resources

- CDC's HEADS UP initiative to improve prevention, recognition, and response to concussion and other serious brain injuries among youth.

- CDC's Traumatic Brain Injury website featuring data, reports, and fact sheets.

- CDC's Pediatric Mild TBI Guideline to help healthcare providers take action to improve the health of their patients.

- Contact practices may be defined as those that include drills or scrimmage run at game-speed or using game-like conditions, such as player versus player contact in pads and taking a player to the ground during a tackle.

- Examples of targeting may include making helmet-to-helmet contact or hitting another player above the shoulders.

- Head-first contact involves a player using the top or crown of the helmet to initiate contact with another player.

- Spearing includes intentionally lowering the head and using the top or crown of the helmet to contact or tackle another player.

- Kroshus E, Sonnen AJ, Chrisman SP, Rivara FP. Association between community socioeconomic characteristics and access to youth flag football. Inj Prev. 2019;25(4):278-282. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042677.

- The Aspen Institute. State of Play Central Ohio. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://projectplay.org/communities/central-ohio.

- Logan K, Cuff S. Organized sports for children, preadolescents, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6):e20190997. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-0997.

- Broglio SP, Williams RM, O'Connor KL, Goldstick J. Football players' head-impact exposure after limiting of full-contact practices. J Athl Train. 2016;51(7):511-8. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-51.7.04.

- Graham R, Rivara FP, Ford MA, Spicer CM. Sports-related concussions in youth: improving the science, changing the culture. National Academies Press; 2014.

- Cusimano MD, Nastis S, Zuccaro L. Effectiveness of interventions to reduce aggression and injuries among ice hockey players: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2013;185(1):E57-69. doi:10.1503/cmaj.112017.

- Beaudouin F, Aus der Funten K, Tross T, Reinsberger C, Meyer T. Head injuries in professional male football (soccer) over 13 years: 29% lower incidence rates after a rule change (red card). Br J Sports Med. 2017;53:948-952. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097217.

- Obana KK, Mueller JD, Saltzman BM, et al. Targeting rule implementation decreases concussions in high school football: a national concussion surveillance study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(10):23259671211031191. doi:10.1177/23259671211031191

- Marks ME, Holcomb TD, Pritchard NS, et al. Characterizing exposure to head acceleration events in youth football using an instrumented mouthpiece. Ann Biomed Eng. 2022;50(11):1620-1632. doi:10.1007/s10439-022-03097-7.

- Champagne AA, Distefano V, Boulanger MM, et al. Data-informed intervention improves football technique and reduces head impacts. Med Sci Sports Excerc. 2019;51(11):2366-2374. doi:10.1249/mss.0000000000002046.

- Gellner RA, Campolettano ET, Rowson S. Association between tackling technique and head acceleration magnitude in youth football players. Biomed Sci Instrum. 2018;54(1):39-45.

- Broglio SP, Eckner JT, Martini D, Sosnoff JJ, Kutcher JS, Randolph C. Cumulative head impact burden in high school football. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28(10):2069-78. doi:10.1089/neu.2011.1825.

- Holcomb TD, Marks ME, Stewart Pritchard N, et al. Characterization of Head Acceleration Exposure During Youth Football Practice Drills. J App Biomech. 2023;39(3):157-168. doi:10.1123/jab.2022-0196.

- Kercher K, Steinfeldt JA, Macy JT, Ejima K, Kawata K. Subconcussive head impact exposure between drill intensities in U.S. high school football. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237800. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237800.

- Kelley ME, Kane JM, Espeland MA, et al. Head impact exposure measured in a single youth football team during practice drills. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2017;20(5):489-497. doi:10.3171/2017.5.PEDS16627.

- Kelley ME, Espeland MA, Flood WC, et al. Comparison of head impact exposure in practice drills among multiple youth football teams. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019;23(3):381-389. doi:10.3171/2018.9.PEDS18314.

- Daugherty J, DePadilla L, Sarmiento K. Assessment of HEADS UP online training as an educational intervention for sports officials/athletic trainers. J Safety Res. 2020;74:133-141. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2020.04.015.

- Daugherty J, DePadilla L, Sarmiento K. Effectiveness of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HEADS UP coaches' online training as an educational intervention. Health Educ J. 2019;78(7):784-797. doi:10.1177/0017896919846185.

- Kerr ZY, Yeargin S, Valovich McLeod TC, et al. Comprehensive coach education and practice contact restriction guidelines result in lower injury rates in youth American football. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;3(7):1-8. doi:10.1177/2325967115594578

- Register-Mihalik J, Baugh C, Kroshus E, Z YK, Valovich McLeod TC. A multifactorial approach to sport-related concussion prevention and education: application of the socioecological framework. J Athl Train. 2017;52(3):195-205. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-51.12.02.

- Patricios JS, Schneider KJ, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport–Amsterdam, 2022. Br J Sport Med. 2023;57(11):695-711. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2023-106898.

- Kroshus E, Cameron KL, Coatsworth JD, et al. Improving concussion education: consensus from the NCAA-Department of Defense Mind Matters Research & Education Grand Challenge. Br J Sport Med. 2020;54:1314-1320. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-102185.

- Kontos AP, Elbin RJ, Fazio-Sumrock VC, et al. Incidence of sports-related concussion among youth football players aged 8-12 years. J Pediatr. 2013;163(3):717-20. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.011.

- Zuckerman SL, Totten DJ, Rubel KE, Kuhn AW, Yengo-Kahn AM, Solomon GS. Mechanisms of injury as a diagnostic predictor of sport-related concussion severity in football, basketball, and soccer: results from a regional concussion registry. Neurosurgery. 2016;63 Suppl 1:102-112. doi:10.1227/neu.0000000000001280.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Position statement: tackling in youth football. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1419-30. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-3282.

- Alosco M, Kasimis A, Stamm J, et al. Age of first exposure to American football and long-term neuropsychiatric and cognitive outcomes. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(9). doi:10.1038/tp.2017.197.

- Mez J, Daneshvar DH, Kiernan PT, et al. Clinicopathological evaluation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in players of American football. JAMA. 2017;318(4):360-370. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.8334.

- Swartz EE, Register-Mihalik JK, Broglio SP, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: reducing intentional head-first contact behavior in American football players. J Athl Train. 2022;57(2):113-124. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-0062.21

- Montenigro PH, Alosco ML, Martin BM, et al. Cumulative head impact exposure predicts later-life depression, apathy, executive dysfunction, and cognitive impairment in former high school and college football players. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(2):328-340. doi:10.1089/neu.2016.4413.

- Boden BP, Tacchetti RL, Cantu RC, Knowles SB, Mueller FO. Catastrophic head injuries in high school and college football players. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1075-81. doi:10.1177/0363546507299239.

- Broglio SP, Sosnoff JJ, Shin S, He X, Alcaraz C, Zimmerman J. Head impacts during high school football: a biomechanical assessment. J Athl Train. 2009;44(4):342-9. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-44.4.342.

- Crisco JJ, Wilcox BJ, Beckwith JG, et al. Head impact exposure in collegiate football players. J Biomech. 2011;44(15):2673-8. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.08.003.

- Greenwald RM, Gwin JT, Chu JJ, Crisco JJ. Head impact severity measures for evaluating mild traumatic brain injury risk exposure. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(4):789-98; discussion 798. doi:10.1227/01.neu.0000318162.67472.ad

- These actions are adapted from recommendations and findings in:

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Policy statement: tackling in youth football. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1419-e1430. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-3282.

- Eliason PH, Galarneau J, Kolstad AT, et al. Prevention strategies and modifiable risk factors for sport-related concussions and head impacts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sport Med. 2023;57:749-761. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-106656.

- Parsons JT, Anderson SA, Casa DJ, et al. Preventing catastrophic injury and death in collegiate athletes: interassociation recommendations endorsed by 13 medical and sports medicine organisations. Br J Sport Med. 2020;54:208-215. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101090.

- Patricios JS, Schneider KJ, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport–Amsterdam, October 2022. Br J Sport Med. 2023;57:695-711. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2023-106898.

- Pankow, M.P., Syrydiuk, R.A., Kolstad, A.T. et al. Head games: a systematic review and meta-analysis examining concussion and head impact incidence rates, modifiable risk factors, and prevention strategies in youth tackle football. Sports Med 52, 1259–1272 (2022). doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01609-4.

- Swartz EE, Register-Mihalik JK, Broglio SP, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: reducing intentional head-first contact behavior in American football players. J Athl Train. 2022;57(2):113-124. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0062.21.

- Waltzman D, Sarmiento K, Devine O, et al. Head impact exposures among youth tackle and flag American football athletes. Sports Health. 2021;13(5):454-462. doi:10.1177/1941738121992324.