At a glance

Hookahs are water pipes that people use to smoke specially made tobacco. Smoking hookah has many of the same health risks as smoking cigarettes. Although youth hookah use has declined in the past decade, continue to monitor of hookah use and implement effective youth interventions, media campaigns, and proven tobacco prevention policies that may further reduce youth hookah use.

Hookahs

Hookahs are water pipes that people use to smoke specially made tobacco.1

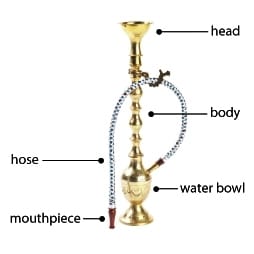

Hookahs vary in size, shape, and style.1 A typical modern hookah has:23

- A head (with holes in the bottom)

- A metal body

- A water bowl

- A flexible hose with a mouthpiece.

Hookah smoking is NOT a safe alternative to smoking cigarettes.1

Hookah tobacco comes in different flavors, such as apple, mint, cherry, chocolate, coconut, licorice, cappuccino, and watermelon.1

People typically smoke hookah in groups, with the same mouthpiece passed from person to person.123

Newer forms of hookah products include electronic hookah products, such as steam stones and hookah pens.

- These products are battery-powered and turn liquid containing nicotine, flavorings, and other chemicals into an aerosol, which a person inhales.4

- Limited information is currently available on the health risks of electronic tobacco products, including electronic hookahs.45

Other names for hookah include narghile, argileh, shisha, hubble-bubble, and goza.1

Health effects of using hookahs

Tip

Hookah and toxin exposure

- Hookah smoke contains many of the same harmful components found in cigarette smoke, such as nicotine, tar, and heavy metals. Nicotine is the same highly addictive chemical found in other tobacco products.1367

- Hookahs expose tobacco to high heat from burning charcoal. The tobacco smoke created by this is at least as toxic as cigarette smoke.1

- The charcoal used to heat the hookah tobacco can also produce high levels of carbon monoxide, metals, and cancer-causing chemicals. This may put those who use hookah at additional health risk.138

- The water in a hookah does not filter smoke. Even after the hookah smoke passes through the water, the smoke has high levels of toxic agents.3

- Smoking hookah can lead to greater exposure to the toxic substances in tobacco smoke than smoking cigarettes.1368

- A person who smokes hookah for an hour—a typical amount of time—inhales much more smoke (about 90,000 ml), or 100–200 times more, than a person who smokes a single cigarette (about 500–600 ml).58

- In a single smoking session, a person using a hookah can be exposed to nearly 9 times more carbon monoxide and 1.7 times more nicotine than from a single cigarette.

- A person who smokes hookah for an hour—a typical amount of time—inhales much more smoke (about 90,000 ml), or 100–200 times more, than a person who smokes a single cigarette (about 500–600 ml).58

Hookah and disease risk

- People who smoke hookah may be at risk for some of the same health effects as people who smoke cigarettes, including some types of cancer and reduced lung function.23

- Hookah smoking may increase the risk of cancer.

- Hookah smoking may increase the risk of heart disease.

- Hookah smoking may negatively impact lung health.

- Sweeteners and flavorings in hookah tobacco products may increase the risk of exposure to smoke-related toxins. This may lead to negative health effects on the lungs of people who smoke these products.9

- Sweeteners and flavorings in hookah tobacco products may increase the risk of exposure to smoke-related toxins. This may lead to negative health effects on the lungs of people who smoke these products.9

- Hookah smoking during pregnancy can impact the health of babies.

Hookah and secondhand smoke

Nontobacco hookah products

Sweetened and flavored nontobacco products are sold for use in hookahs.12 Marketing for these products often suggests they are less harmful to health than smoking tobacco.13 However, studies of tobacco-based shisha and "herbal" shisha show that smoke from both preparations contains carbon monoxide and other toxic agents. These toxins are known to increase the risk for smoking-related cancers, heart disease, and lung disease.1314

Hookah use in the United States

- · In 2022, the Monitoring the Future survey found that —15

- Smoking tobacco with a hookah in the past 12 months decreased significantly from 20.6% in 2014 to 8.0% in 2022 among young adults aged 19–30.

- In 2022, the percentage of young adults who smoked hookah in the last 12 months was similar among those in college (5.6%) and those not in college (5.7%).

- Smoking tobacco with a hookah in the past 12 months decreased significantly from 20.6% in 2014 to 8.0% in 2022 among young adults aged 19–30.

- The 2024 National Youth Tobacco Survey found that approximately 0.6% of U.S. middle school students (60,000) and 0.8% of high school students (120,000) smoked tobacco in a hookah during the past 30 days.16

- In 2023, the Monitoring the Future survey found that—17

- Nearly 1 in every 36 (2.7%) 12th grade high school students in the United States used a hookah to smoke tobacco in the past 12 months.

- Annual hookah use among 12th graders has declined over the past decade. Although hookah use increased between 2010 (17.1%) and 2014 (22.9%), it decreased in 2018 (7.8%) and further declined in 2023 (2.7%).1718

- Hookah use varied by region. The highest prevalence of use was in the Northeast, where nearly 1 in 20 (4.7%) 12th graders used a hookah to smoke tobacco in the past 12 months.

- Nearly 1 in every 36 (2.7%) 12th grade high school students in the United States used a hookah to smoke tobacco in the past 12 months.

Addressing use of hookah

What to know

People in any sector, including government, parents or teachers, and health professionals, can take action to prevent the use of hookah and help people quit. Implementing policies can reduce the number of people who smoke hookah. Free resources, like quitlines and websites, can help you or someone you know quit.

States, communities, tribes, and territories can fairly and equitably implement evidence-based, population-level strategies that address the use of all forms of tobacco products, including hookah. These strategies include:

- Licensing retailers who sell any type of tobacco product. This strategy identifies who sells hookah and other tobacco products. It also makes equitable implementation and enforcement of tobacco control policies possible.

- Prohibiting sales of flavored hookah and other tobacco products. Studies of local U.S. policies show that restricting the sale of flavored tobacco products reduces tobacco use.1920

- Raising the price of hookah and other tobacco products and prohibiting price discounts.

- Reducing the advertising and marketing of hookah and other tobacco products to young people.

- Ensuring that all people who use tobacco products have access to evidence-based quitting resources to help them quit successfully. This includes counseling and medication.

- Tailoring cessation messages to better reach people who use hookah.

- Developing educational initiatives that describe targeted tobacco industry marketing tactics. These initiatives also warn about the risks of tobacco product use, including hookah.

- American Lung Association. Facts About Hookah. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/smoking-facts/health-effects/facts-about-hookah.

- Akl EA, Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, Honeine R, Jaoude PA, Irani J. The Effects of Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking on Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(3):834–857.

- Cobb CO, Ward KD, Maziak W, Shihadeh AL, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: An Emerging Health Crisis in the United States. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34(3):275–285.

- U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2016. Accessed March 18, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/e-cigarettes/pdfs/2016_sgr_entire_report_508.pdf

- Stratton K, Kwan LY, Eaton DL, eds. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. The National Academies Press; 2018.

- U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, 2012. Accessed March 18, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99237/

- Shihadeh A. Investigation of mainstream smoke aerosol of the argileh water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol. 2003;41(1):143–152.

- World Health Organization. Advisory Note: Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: Health Effects, Research Needs and Recommended Actions by Regulators, 2nd edition. World Health Organization, WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation (TobReg); 2015. Accessed March 18, 2021. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/161991/9789241508469_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Kassem NOF, Strongin RM, Stroup AM, et al. Toxicity of Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: The Role of Flavors, Sweeteners, Humectants, and Charcoal.Toxicol Sci. 2024:kfae095.

- Nuwayhid IA, Yamout B, Azar G, Al Kouatly Kambris M. Narghile (Hubble-Bubble) Smoking, Low Birth Weight and Other Pregnancy Outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(4):375–383.

- El-Hakim IE, Uthman MA. Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Keratoacanthoma of the Lower Lip Associated with "Goza" and "Shisha" Smoking. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(2):108–110.

- Cobb CO, Vansickel AR, Blank MD, Jentink K, Travers MJ, Eissenberg T. Indoor Air Quality in Virginia Waterpipe Cafés. Tob Control. 2013;22(5):338–343.

- Shihadeh A, Salman R, Jaroudi E, et al. Does Switching to a Tobacco-Free Waterpipe Product Reduce Toxicant Intake? A Crossover Study Comparing CO, NO, PAH, Volatile Aldehydes, Tar and Nicotine Yields. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50(5):1494–1498.

- Blank MD, Cobb CO, Kilgalen B, et al. Acute Effects of Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Control Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116(1–3):102–109.

- Patrick ME, Miech RA, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM. Monitoring the Future: Panel Study Annual Report: National data on substance use among adults ages 19 to 60, 1976-2022. National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health; 2022. https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/mtfpanel2023.pdf

- Jamal A, Park-Lee, E, Birdsey J, et al. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students — National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73(41):917–924.

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, Patrick ME, O'Malley PM. Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2023: Overview and Detailed Results for Secondary School Students. National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health; 2024. https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/mtfoverview2024.pdf

- Johnston DL, Miech RA, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975–2018: 2018 Overview Key Findings on Adolescents Drug Use. National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health; 2019. Accessed March 18, 2021. https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/mtf-overview2018.pdf

- Rogers T, Brown EM, Siegel-Reamer L, et al. A Comprehensive Qualitative Review of Studies Evaluating the Impact of Local US Laws Restricting the Sale of Flavored and Menthol Tobacco Products. Nicotine Tob Res. 2022;24(4):433–443.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Scientific Assessment of the Impact of Flavors in Cigar Products. U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Tobacco Products, 2022. Accessed March 18, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/157595/download

- Birdsey J, Cornelius M, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among U.S. Middle and High School Students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(44):1173–1182.

- Campaign for Tobacco-free Kids. States & Localities That Have Restricted The Sale of Flavored Tobacco Products. 2024. Accessed March 18, 2021. https://assets.tobaccofreekids.org/factsheets/0398.pdf