At a glance

This page describes the latest technology used for detecting foodborne outbreaks, and explains how PulseNet has evolved over time and helps its partners in the network.

Using New Technology to Detect Outbreaks

For over 20 years, PulseNet, has helped public health scientists identify and solve outbreaks of foodborne illness in the United States. PulseNet recently updated the technology it uses to detect outbreaks. This new technology, whole genome sequencing, gives public health scientists more information than ever before about the foodborne bacteria that make people sick. It improves investigators' ability to link cases of illness to outbreaks and to identify common sources of infection. Based on CDC's experience with whole genome sequencing, CDC expects to identify and solve more outbreaks and prevent more illnesses as WGS becomes the new standard in PulseNet for surveillance of foodborne bacteria.

What does whole genome sequencing show us?

Whole genome sequencing is a process to determine the genetic makeup (or content) of bacteria by reading their DNA. Public health scientists use this technique to compare bacteria making people sick to identify outbreaks. They also use it to learn why some bacteria make people more sick or are more resistant to antibiotics than others.

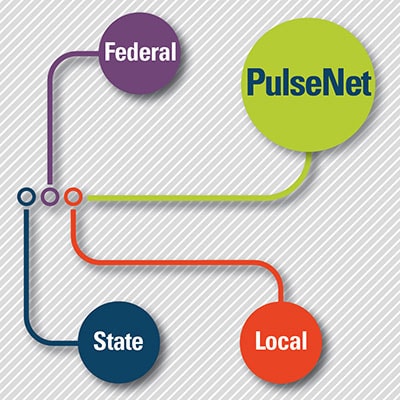

Connecting Partners Committed to Food Safety

PulseNet is made up of 82 federal, state, and local public health laboratories in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. These labs use standardized laboratory and data analysis methods to characterize the foodborne bacteria making people sick. PulseNet's standardized tools allow public health labs around the country to work together in a coordinated network to monitor for potential outbreaks by analyzing and comparing data from laboratory samples.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) information is only one clue in solving a foodborne disease outbreaks. Investigators also need information gathered outside the laboratory, such as the places people went and the food they ate before they got sick; and public health departments need strong workforces to collect this information. WGS information supports the epidemiological investigations and helps public health investigators identify and solve more outbreaks while they are still small. Successful outbreak investigations help identify unsafe foods and production processes. Regulatory agencies and industry can use this new knowledge to prevent future illness.

Staying Ahead of the Curve

Whole genome sequencing improves the ability of public health scientists to connect the dots between sick people and sources of infection. To best use this advanced technology, we must continue to support and develop state laboratory capacity, and also support state capacity to investigate foodborne outbreaks and illnesses. CDC is committed to supporting state and local health departments with the resources and training needed to cultivate highly skilled epidemiologists and laboratory scientists.

PulseNet scientists at CDC are constantly working to advance laboratory and data analysis tools used to investigate outbreaks. By researching and developing new technologies beyond WGS, CDC scientists will be able to ensure that the PulseNet laboratory network remains cutting-edge.

Investing in Results

- 1996 – PulseNet Laboratory Network Established

- Funding speeds progress of food safety, advanced molecular detection (AMD), and antibiotic resistance initiatives

- 2013 – CDC uses WGS for routine surveillance of Listeria

- 2014 – WGS projects funded by AMD results in more detailed foodborne outbreak detection

- 2016 – CDC and select states expand the use of WGS for routine surveillance of Campylobacter, E.coli, and Salmonella

- 2019 – WGS is the new PulseNet gold standard for identifying foodborne pathogens

Beyond 2019

CDC and PulseNet are advancing laboratory and data analysis tools used for investigating, detecting, and solving outbreaks. Novel technologies such as metagenomics allow detection of foodborne bacterial DNA directly from patient samples.