Daily Screen Time Among Teenagers: United States, July 2021–December 2023

NCHS Data Brief No. 513, October 2024

PDF Version (489 KB)

Benjamin Zablotsky, Ph.D., Basilica Arockiaraj, M.P.H., Gelila Haile, M.P.H., and Amanda E. Ng, Ph.D., M.P.H.

- Key findings

- About one-half of teenagers had 4 hours or more of daily screen time.

- The percentage of teenagers with 4 hours or more of daily screen time varied by age and race and Hispanic origin.

- The percentage of teenagers with 4 hours or more of daily screen time varied by parental education and urbanization level.

- The percentage of teenagers who had symptoms of anxiety or depression in the past 2 weeks was higher among those with 4 hours or more of daily screen time.

Data from the National Health Interview Survey–Teen

- During July 2021 through December 2023, one-half of teenagers ages 12–17 had 4 hours or more of daily screen time (50.4%).

- Black non-Hispanic teenagers were most likely to have 4 hours or more of daily screen time (60.4%) compared with teenagers in other race and Hispanic-origin groups.

- Teenagers living in metropolitan areas were more likely to have 4 hours or more of daily screen time than teenagers living in nonmetropolitan areas.

- About 1 in 4 teenagers with 4 hours or more of daily screen time have experienced anxiety (27.1%) or depression symptoms (25.9%) in the past 2 weeks.

As technology has become more integrated into teenagers’ lives, the time spent in front of screens has continued to rise in the United States (1). High levels of screen time have been linked with adverse health outcomes, including poor sleep habits, fatigue, and symptoms of anxiety and depression (2–4). Using data from the July 2021–December 2023 National Health Interview Survey–Teen (NHIS–Teen), this report describes the prevalence of daily screen time among teenagers ages 12–17 by selected characteristics. Teenagers reported on their own screen time use during a typical weekday, excluding time spent doing schoolwork.

Keywords: adolescent health, prevalence, anxiety, depression, National Health Interview Survey–Teen (NHIS–Teen)

About one-half of teenagers had 4 hours or more of daily screen time.

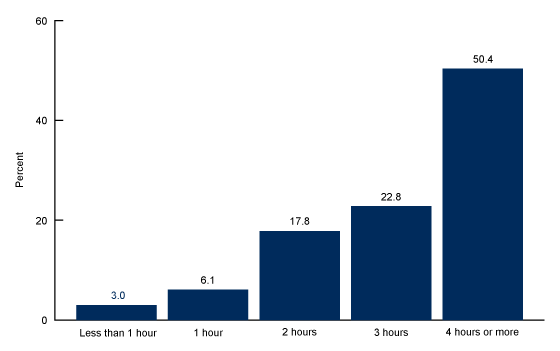

- During July 2021 through December 2023, 50.4% of teenagers ages 12–17 had 4 hours or more of daily screen time, 22.8% had 3 hours, 17.8% had 2 hours, 6.1% had 1 hour, and 3.0% had less than 1 hour of daily screen time (Figure 1, Table 1).

Figure 1. Percent distribution of teenagers ages 12–17, by hours of daily screen time: United States, July 2021–December 2023

NOTES: Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Total does not add up to 100 due to rounding.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey – Teen, July 2021–December 2023.

The percentage of teenagers with 4 hours or more of daily screen time varied by age and race and Hispanic origin.

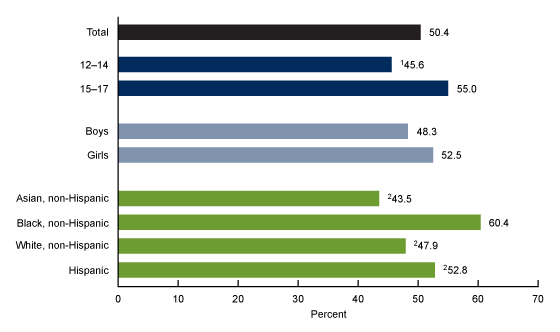

- Teenagers ages 15–17 (55.0%) were more likely than those ages 12–14 (45.6%) to have4 hours or more of daily screen time (Figure 2, Table 2).

- The observed difference in 4 hours or more of daily screen time between boys (48.3%) and girls (52.5%) was not significant.

- Black non-Hispanic (subsequently, Black) teenagers (60.4%) were more likely than Hispanic (52.8%), Asian non-Hispanic (subsequently, Asian) (43.5%), and White non-Hispanic (subsequently, White) (47.9%) teenagers to have 4 hours or more of daily screen time. Differences between other race and Hispanic-origin groups were not significant.

Figure 2. Percentage of teenagers ages 12–17 with 4 or more hours of daily screen time, by age, sex, and race and Hispanic origin: United States, July 2021–December 2023

1Significantly different from teenagers ages 15–17 (p < 0.05).

2Significantly different from Black non-Hispanic teenagers (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Teenagers of Hispanic origin may be of any race. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey–Teen, July 2021–December 2023.

The percentage of teenagers with 4 hours or more of daily screen time varied by parental education and urbanization level.

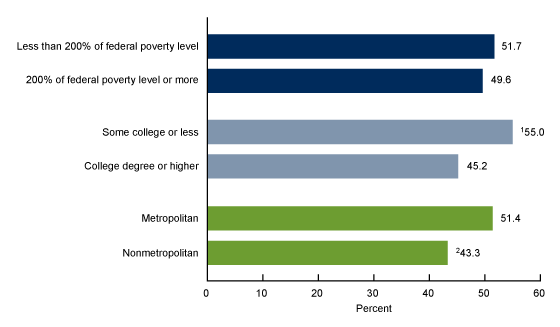

- The percentage of teenagers ages 12–17 living in families with incomes of less than 200% of the federal poverty level with 4 hours or more of daily screen time (51.7%) was comparable to the percentage of teenagers living in families with incomes of 200% of the federal poverty level or more (49.6%) (Figure 3, Table 3).

- Teenagers living in families where the highest parental education was some college or less were more likely to have 4 hours or more of daily screen time (55.0%) compared with teenagers living in families where the highest parental education was a college degree or higher (45.2%).

- Teenagers living in metropolitan areas were more likely to have 4 hours or more of daily screen time (51.4%) compared with teenagers living in nonmetropolitan areas (43.3%).

Figure 3. Percentage of teenagers ages 12–17 with 4 or more hours of daily screen time, by family income, highest parental education, and urbanization level: United States, July 2021–December 2023

1Significantly different from teenagers living in families where the highest educated parent had a college degree or higher (p < 0.05).

2Significantly different from teenagers living in metropolitan areas (p < 0.05).

NOTE: Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey–Teen, July 2021–December 2023.

The percentage of teenagers who had symptoms of anxiety or depression in the past 2 weeks was higher among those with 4 hours or more of daily screen time.

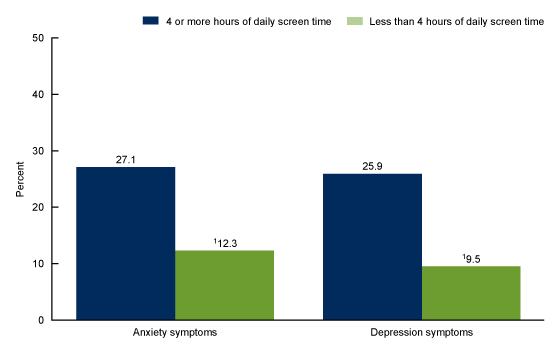

- During July 2021 through December 2023, about 1 in 4 teenagers ages 12–17 with 4 hours or more of daily screen time had experienced anxiety (27.1%) or depression (25.9%) symptoms in the past 2 weeks (Figure 4, Table 4).

- Teenagers who had 4 or more hours of daily screen time were more likely to have had anxiety symptoms in the past 2 weeks (27.1%) compared with teenagers with less than4 hours of daily screen time (12.3%).

- Teenagers who had 4 or more hours of daily screen time were more likely to have had depression symptoms in the past 2 weeks (25.9%) compared with teenagers with less than4 hours of daily screen time (9.5%).

Figure 4. Percentage of teenagers ages 12–17 who had symptoms of anxiety or depression in the past 2 weeks, by daily screen time: United States, July 2021–December 2023

1Significantly different from teenagers with 4 or more hours of daily screen time (p < 0.05).

NOTE: Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey–Teen, July 2021–December 2023.

Summary

During July 2021 through December 2023, 50.4% of teenagers self-reported 4 hours or more of daily screen time. Teenagers who were Black, older (ages 15–17), living in metropolitan areas, or living in families with lower parental education were most likely to have 4 hours or more of daily screen time. Teenagers with higher daily screen time were more likely to experience both anxiety and depression symptoms over the past 2 weeks, which is consistent with previous research (3,4).

As technology and screens continue to develop, their influence on the lives of children changes, making it increasingly important to expand our understanding of the patterns of screen time use overall and among selected subgroups (5).

Definitions

Anxiety symptoms: Measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–2 (GAD–2) scale (6). Teenagers were asked, “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge?” and “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by not being able to stop or control worrying?” Response options were “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day,” with scores assigned as zero, one, two, or three, respectively. Teenagers who scored three or more on the two questions combined were considered to have symptoms of anxiety per GAD–2 scoring guidelines. Teenagers who did not answer both questions were excluded.

Depression symptoms: Measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ–2) (7). Teenagers were asked, “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?” and “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?” Like the GAD–2, response options were “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day,” with scores assigned as zero, one, two, or three, respectively. Teenagers who scored three or more on the two questions combined were considered to have symptoms of depression per PHQ–2 scoring guidelines. Teenagers who did not answer both questions were excluded.

Family income as a percentage of the federal poverty level: Based on the federal poverty level, which was calculated from the family’s income in the previous calendar year and family size using the U.S. Census Bureau’s poverty thresholds (8). Family income was imputed when missing (9).

Parental education: Reflects the highest education level completed by the teenager’s parent or parents who lived in the household, regardless of the parent’s age. Information on parents not living in the household was not obtained. If both parents lived in the household but information on one parent’s education was unknown, the other parent’s education was used. If both parents lived in the household and education was coded as missing for both, or no parents lived in the household, parental education was unknown.

Race and Hispanic origin: Teenagers categorized as non-Hispanic indicated one race only; respondents had the option to select more than one racial group. Hispanic teenagers could be of any race or combination of races. Estimates for non-Hispanic children of races other than Asian, Black, and White are not shown due to the inability to make statistically reliable estimates for these groups, but they are included in total estimates.

Screen time: Based on the response to the question, “On most weekdays, how many hours do you spend a day in front of a TV, computer, cellphone or other electronic device watching programs, playing games, accessing the internet, or using social media?” Respondents were instructed not to include time spent for schoolwork. Response options were “Less than 1 hour; 1 hour; 2 hours; 3 hours; 4 or more hours.”

Urbanization level: Metropolitan size and status were determined using the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics urban–rural classification scheme for counties (10), by merging the geographic federal information processing standard codes for the county of household residence with the county-level federal information processing standard codes from the classification scheme’s data set. Metropolitan includes large central, large fringe, medium, and small metropolitan counties. Nonmetropolitan includes micropolitan and noncore counties.

Data source and methods

NHIS–Teen is a web-based, self-administered follow-back survey of adolescents sampled in NHIS as part of the Sample Child interview. It includes adolescents ages 12–17 whose parent completed the NHIS Sample Child interview and provided permission for their teenager to be invited to participate in NHIS–Teen. Eligible teenagers received an invitation letter and a series of planned reminders with instructions for completing a 15-minute online health survey. On average, teenagers completed the survey within 2 to 3 weeks of the parent interview.

NHIS–Teen covers topics such as physical activity, sedentary activity, use of social media and electronic devices, friendships, bullying, symptoms of poor mental health, and resilience as reported by teenagers themselves. The parent permission rate for NHIS–Teen was 60.4%, and the teen participation rate was 46.2%, resulting in an overall NHIS–Teen interview rate of 27.9%. More detailed information about NHIS–Teen, including its methodology and recruitment strategy, has been previously published (11).

Teen and family characteristics are based on data provided by the teenager’s parent as part of the NHIS Sample Child interview. Point estimates and the corresponding confidence intervals were calculated using SAS-callable SUDAAN software (12) to account for the complex sample design of NHIS–Teen. All estimates in this report meet National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions (13). Differences between percentages were evaluated using two-sided significance tests at the 0.05 level.

About the authors

Benjamin Zablotsky, Basilica Arockiaraj, Gelila Haile, and Amanda E. Ng are with the National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health Interview Statistics. At the time of this report, Basilica Arockiaraj and Gelila Haile were guest researchers at the National Center for Health Statistics through the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education fellowship program.

References

- Qi J, Yan Y, Yin H. Screen time among school-aged children of aged 6–14: A systematic review. Glob Health Res 8(12). 2023. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-023-00297-z.

- Alshoaibi Y, Bafil W, Rahim M. The effect of screen use on sleep quality among adolescents in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care 12(7):1379–88. 2023. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_159_23.

- Hmidan A, Seguin D, Duerden EG. Media screen time use and mental health in school aged children during the pandemic. BMC Psychol 11(1):202. 2023. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01240-0.

- Twenge JM, Campbell WK. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev Med Rep 12:271–83. 2018. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medr.2018.10.003.

- Zhu X, Griffiths H, Xiao Z, Ribeaud D, Eisner M, Yang Y, Murray AL. Trajectories of screen time across adolescence and their associations with adulthood mental health and behavioral outcomes. J Youth Adolesc 52(7):1433–47. 2023. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01782-x.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 146(5):317–25. 2007.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire–2: Validity of a

two-item depression screener. Med Care 41(11):1284–92. 2003. - U.S. Census Bureau. Poverty thresholds. 2021.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple imputation of family income in 2022 National Health Interview Survey: Methods. 2023.

- Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS urban–rural classification scheme for counties. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(166). 2014.

- Zablotsky B, Black LI, Ng AE, Bose J, Jones J, Maitland A, Blumberg SJ. Methodology report for the 2021–2023 National Health Interview Survey–Teen 30-month file. 2024.

- RTI International. SUDAAN (Release 11.0.3) [computer software]. 2018.

- Parker JD, Talih M, Malec DJ, Beresovsky V, Carroll M, Gonzalez JF Jr, et al. National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(175). 2017.

Suggested citation

Zablotsky B, Arockiaraj B, Haile G, Ng AE. Daily screen time among teenagers: United States, July 2021–December 2023. NCHS Data Brief, no 513. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2024. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc/168509.

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health Statistics

Brian C. Moyer, Ph.D., Director

Amy M. Branum, Ph.D., Associate Director for Science

Division of Health Interview Statistics

Stephen J. Blumberg, Ph.D., Director

Anjel Vahratian, Ph.D., M.P.H, Associate Director for Science