Prevalence of Tooth Loss Among Older Adults: United States, 2015–2018

- Key findings

- What was the prevalence of complete tooth loss among older adults in 2015–2018?

- What were the differences in the prevalence of complete tooth loss among older adults by race and Hispanic origin in 2015–2018?

- What were the differences in the prevalence of complete tooth loss among older adults by education level in 2015–2018?

- What were the age-adjusted trends in complete tooth loss among older adults from 1999–2000 through 2017–2018?

- Summary

- Definitions

- Data source and methods

- About the authors

- References

- Suggested citation

PDF Version (429 KB)

Key findings

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

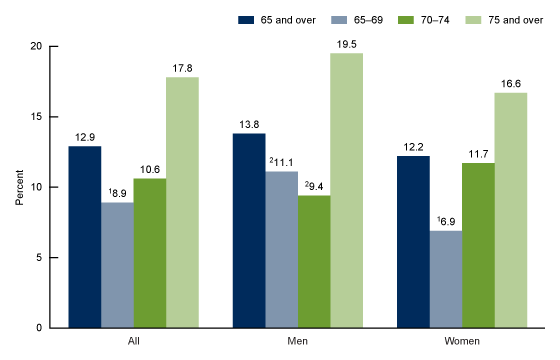

- Prevalence of complete tooth loss among adults aged 65 and over was 12.9% and increased with age: 8.9% (ages 65–69), 10.6% (ages 70–74), and 17.8% (ages 75 and over).

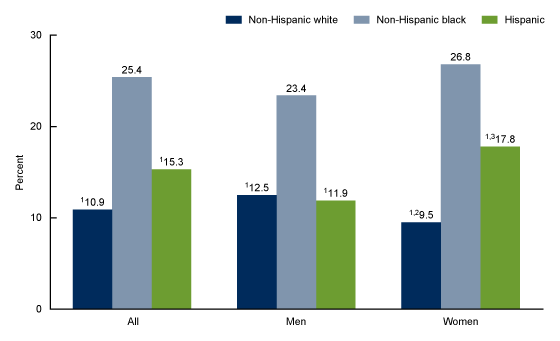

- Non-Hispanic black older adults (25.4%) had a higher prevalence of complete tooth loss than Hispanic (15.3%) and non-Hispanic white (10.9%) older adults.

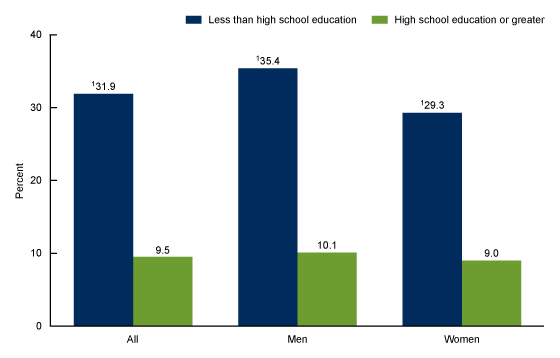

- Prevalence of complete tooth loss was higher for older adults with less than a high school education (31.9%) compared with those with a high school education or greater (9.5%).

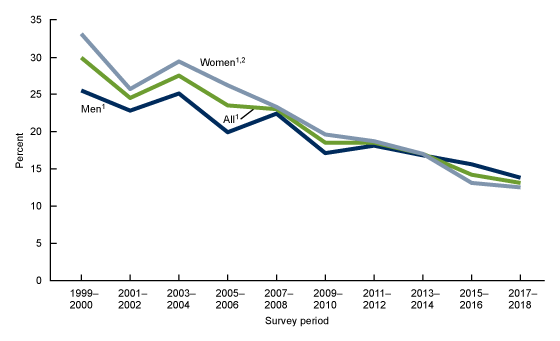

- From 1999–2000 through 2017–2018, the age-adjusted prevalence of complete tooth loss among all older adults declined significantly.

Complete tooth loss can diminish quality of life, limiting food choices and impeding social interaction (1). Reducing complete tooth loss is a national health goal monitored by Healthy People; although prevalence has decreased since the 1960s, disparities persist (2–4). Factors leading to complete tooth loss—untreated dental caries, periodontitis, and smoking—are preventable and differ by socioeconomic status and between men and women (5,6). This report examines disparities in complete tooth loss among U.S. adults aged 65 and over by sex, age, race and Hispanic origin, and education in 2015–2018 and trends from 1999–2000 through 2017–2018.

Keywords: oral health, NHANES

What was the prevalence of complete tooth loss among older adults in 2015–2018?

The prevalence of complete tooth loss among adults aged 65 and over was 12.9% in 2015–2018 (Figure 1). Prevalence increased with age, overall (8.9% for adults aged 65–69, 10.6% for ages 70–74, and 17.8% for ages 75 and over) and among women (6.9% for ages 65–69, 11.7% for ages 70–74, and 16.6% for ages 75 and over). Among men, complete tooth loss was higher in the oldest age group (19.5% for 75 and over) compared with the two younger groups (11.1% and 9.4%, respectively, for those aged 65–69 and 70–74). No significant differences in prevalence between men and women were observed.

Figure 1. Prevalence of complete tooth loss among adults aged 65 and over, by sex and age: United States, 2015–2018

1Significant linear trend with increasing age.

2Significant difference from men aged 75 and over.

NOTE: Access data table for Figure 1.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015–2018.

What were the differences in the prevalence of complete tooth loss among older adults by race and Hispanic origin in 2015–2018?

Overall, the prevalence of complete tooth loss was significantly higher among non-Hispanic black older adults (25.4%) compared with Hispanic (15.3%) and non-Hispanic white (10.9%) older adults (Figure 2).

Among men, prevalence was also higher among non-Hispanic black men (23.4%) compared with non-Hispanic white (12.5%) and Hispanic (11.9%) men. Among women, prevalence of complete tooth loss was higher in non-Hispanic black women (26.8%) compared with Hispanic (17.8%) and non-Hispanic white (9.5%) women. Prevalence was also higher among Hispanic women compared with non-Hispanic white women.

Among Hispanic older adults, prevalence of complete tooth loss was higher among women than in men.

Figure 2. Prevalence of complete tooth loss among adults aged 65 and over, by sex and race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2015–2018

1Significant difference from non-Hispanic black persons.

2Significant difference from Hispanic persons.

3Significant difference from Hispanic men.

NOTE: Access data table for Figure 2.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015–2018.

What were the differences in the prevalence of complete tooth loss among older adults by education level in 2015–2018?

In 2015–2018, the prevalence of complete tooth loss among older adults was higher among adults with less than a high school education (31.9%) compared with adults with a high school education or greater (9.5%) (Figure 3). Similarly, the prevalence of complete tooth loss was 35.4% among men with less than a high school education and 10.1% among men with a high school education or greater. For women, the prevalence of complete tooth loss was 29.3% among those with less than a high school education and 9.0% among those with a high school education or greater. No significant differences were noted by education level between men and women.

Figure 3. Prevalence of complete tooth loss among adults aged 65 and over, by education level: United States, 2015–2018

1Significant difference from adults with a high school education or greater.

NOTE: Access data table for Figure 3.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015–2018.

What were the age-adjusted trends in complete tooth loss among older adults from 1999–2000 through 2017–2018?

From 1999–2000 through 2017–2018, the age-adjusted prevalence of complete tooth loss decreased from 29.9% to 13.1% (Figure 4). Prevalence also decreased among men from 25.5% to 13.8% and among women from 33.1% to 12.5%. In 1999–2000, 2003–2004, and 2005–2006 the prevalence was higher among women than men, while in later years, no significant differences were seen between men and women.

Figure 4. Trends in prevalence of complete tooth loss among adults aged 65 and over, by sex: United States, 1999–2000 through 2017–2018

1Significant, decreasing linear trend from 1999–2000 to 2017–2018.

2Significant difference from men for 1999–2000, 2003–2004, and 2005–2006.

NOTES: Estimates were age adjusted by the direct method to the 2000 U.S. Census population using the age groups 65–69, 70–74, and 75 and over. Access data table for Figure 4.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2018.

Summary

In 2015–2018, the prevalence of complete tooth loss was 12.9% among adults aged 65 and over and increased with age. Non-Hispanic black older adults had the highest prevalence of complete tooth loss (25.4%) compared with other race and Hispanic-origin groups. The only statistically significant difference between men and women was among Hispanic adults, where the prevalence was higher among women compared with men. The prevalence of complete tooth loss among older adults was higher among adults with less education.

From 1999–2000 through 2017–2018, the age-adjusted prevalence of complete tooth loss declined. This pattern is consistent with previous reports of greater percentages of older adults retaining their natural teeth (7). Improved diagnostic tools and restorative treatment modalities like fillings and fixed restorations along with prevention efforts may have resulted in a lower prevalence of complete tooth loss among adults aged 65 and over (1,7).

Definitions

Complete tooth loss: The loss of all natural, permanent teeth..

Education level: Based on an individual’s highest level of education, categorized as less than a high school education and a high school education or greater.

Data source and methods

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a cross-sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) designed to monitor the health and nutritional status of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population (8). The survey consists of home interviews, followed by standardized physical examinations in mobile examination centers. NHANES includes an oral health examination that involves a tooth count assessment. Trained, licensed dentists conduct the oral health examination, assessing the presence of a tooth, whether it is a permanent or primary tooth, and if a root tip is present (9). Tooth count assessments were used in this analysis. Dental examiners followed the same protocol for 1999–2004 and 2011–2018 (9). A basic screening examination methodology was used to conduct the oral health examination in 2005–2010; health technologists conducted the oral health examination in 2005–2008, and licensed dental hygienists conducted the examination in 2009–2010 (10).

The NHANES sample is selected through a complex, multistage probability design. In 2015–2018, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic persons were oversampled; for more information, visit the NHANES website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

Examination weights were used to account for the differential probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and noncoverage. Taylor series linearization was used to compute variance estimates. Differences between groups were evaluated using a univariate t statistic at the p less than 0.05 significance level. All reported estimates meet NCHS presentation standards (11). Linear regression modeling was used to determine the significance of linear trends. Age-adjusted prevalence estimates were used in the time trend analysis. Age-adjustments were done using the direct method to the 2000 projected U.S. Census population using the age groups 65–69, 70–74, and 75 and over. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS for Windows version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C.) and SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, N.C.).

About the authors

Eleanor Fleming is with NCHS’ Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Joseph Afful is with Peraton Corporation. Susan O. Griffin is with the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Oral Health.

References

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health. Oral health in America: A report of the Surgeon General. 2000.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020: Oral health. 2019.

- Gooch BF, Eke PI, Malvitz DM. Public health and aging: Retention of natural teeth among older adults—United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 52(50):1226–9. 2003.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral health surveillance report: Trends in dental caries and sealants, tooth retention, and edentulism, United States, 1999–2004 to 2011–2016. 2019.

- Eke PI, Dya BA, Wei L, Slade GD, Thornton-Evans GO, Borgnakke WS, et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol 86(5):611–22. 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current cigarette smoking among adults in the United States. 2019.

- Griffin SO, Griffin PM, Li CH, Bailey WD, Brunson D, Jones JA. Changes in older adults’ oral health and disparities: 1999 to 2004 and 2011 to 2016. J Am Geriatr Soc 67(6):1152–7. 2019.

- Johnson CL, Dohrmann SM, Burt VL, Mohadjer LK. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Sample design, 2011–2014. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(162). 2014.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Continuous NHANES: 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Continuous NHANES: 2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010.

- Parker JD, Talih M, Malec DJ, Beresovksy V, Carroll M, Gonzalez JF Jr, et al. National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(175). 2017.

Suggested citation

Fleming E, Afful J, Griffin SO. Prevalence of tooth loss among older adults: United States, 2015–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 368. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020.

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health Statistics

Brian C. Moyer, Ph.D., Director

Amy M. Branum, Ph.D., Acting Associate Director for Science

Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys

Ryne Paulose-Ram, M.A., Ph.D., Acting Director

Lara J. Akinbami, M.D., Acting Associate Director for Science