|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Health Information Privacy and Syndromic Surveillance SystemsDaniel Drociuk,1 J.

Gibson,1 J. Hodge, Jr.,2

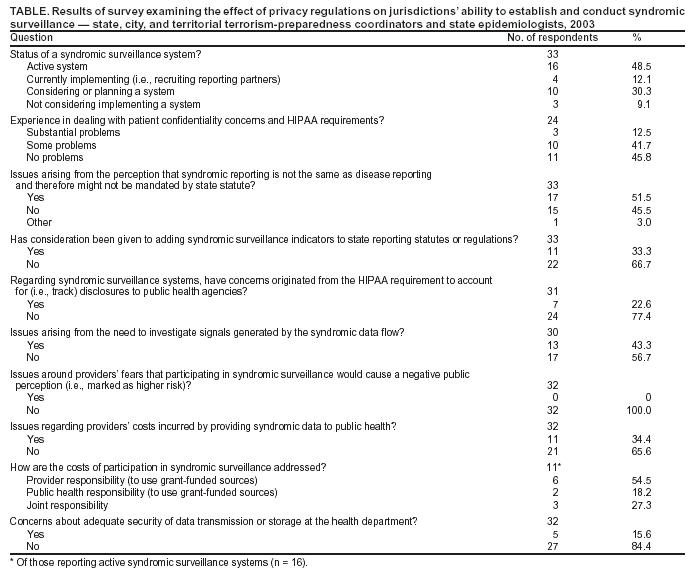

Corresponding author: Daniel Drociuk, 1751 Calhoun Street, Columbia, SC 29201. Telephone: 803-898-0289; Fax: 803-898-0897; E-mail: drociukd@dhec.sc.gov. AbstractThe development of syndromic surveillance systems to detect potential terrorist-related outbreaks has the potential to be a useful public health surveillance activity. However, the perception of how the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy Rule applies to the disclosure of certain public health information might affect the ability of state and local health departments to implement syndromic surveillance systems within their jurisdictions. To assess this effect, a multiple-question survey asked respondents to share their experiences regarding patient confidentiality and HIPAA Privacy Rule requirements when implementing syndromic surveillance systems. This assessment summarizes the results of a national survey of state terrorism-preparedness coordinators and state epidemiologists and reflects the authors' and others' experiences with implementation. IntroductionState and local public health authorities use reports of diagnosed diseases or clinical syndromes to monitor disease or condition patterns (1). Syndromic surveillance refers to the systematic gathering and analysis of prediagnostic health data to rapidly detect clusters of symptoms and health complaints that might indicate an infectious-disease outbreak or other public health threat (2). Examples include electronic monitoring of routinely collected syndromic data (e.g., fever, gastrointestinal illness, or respiratory complaints in emergency departments) and time-sensitive data collection at regional hospitals before, during, or after major public events (e.g., Super Bowl, Salt Lake Winter Olympic Games, or political conventions). Although certain syndromic surveillance activities use nonidentifiable data, the majority of systems require individually identifiable health data to permit rapid and efficient investigation of signals and follow-up with affected persons. As a result, syndromic surveillance systems often require medical providers or others to disclose identifiable health information to state, tribal, or local public health agencies; these data are typically shared with federal public health authorities in a nonidentifiable format. Multiple legal concerns arise from such data practices, including questions about systems' underlying legal authority and the relevance of health information privacy regulations pursuant to the HIPAA Privacy Rule or other health information privacy laws. These legal concerns include the questions of 1) whether state statutory authorization for disease reporting applies to syndromic data; 2) the perceived effect of HIPAA's requirement that covered entities account for disclosures to public health agencies; 3) the effect of HIPAA requirements on investigating signals of possible outbreaks; and 4) the cost to reporting organizations or public health agencies of establishing a flow of syndromic data (3). In particular, public health professionals are concerned about whether potential reporting organizations might be incorrectly citing the HIPAA Privacy Rule to justify their refusal to disclose syndromic health data to public health agencies. To examine these concerns, researchers e-mailed a survey to state epidemiologists and terrorism-preparedness coordinators, asking about the effect of privacy concerns on their ability to establish and conduct syndromic surveillance. Because little has been published on this topic, the survey instrument was designed to be exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than hypothesis-testing. After asking initial questions to determine the status of a state's or city's syndromic surveillance system, the instrument used open-ended questions to capture anecdotal remarks and perceptions regarding barriers to the implementation of syndromic surveillance systems. The survey targeted the 50 states, four localities, and eight territories that are current recipients of CDC cooperative agreements on public health response and terrorism preparedness (4). Responses from county-level entities with syndromic surveillance systems were also accepted and incorporated into respective state-level responses. MethodsData SourcesA survey instrument was developed to assess the impact of the HIPAA Privacy Rule on syndromic surveillance within states. After hypothesis-generating conversations with representatives from two states and one city (Connecticut, Kentucky, and New York City) that have implemented syndromic surveillance systems and with staff of the CDC Division of Public Health Surveillance and Informatics, a multiple-question survey was designed. With funding from CDC cooperative agreements for terrorism preparedness and response, multiple states have explored the implementation of syndromic surveillance systems under the surveillance and epidemiology capacity section (Focus Area B) of these cooperative agreements (4). All states, the District of Columbia, the three largest U.S. municipalities (Los Angeles County, New York City, and Chicago), and eight U.S. territories have received Focus Area B funding. Persons identified as Focus Area B leaders are tasked with operational oversight and implementation of critical capacities and benchmarks pertaining to surveillance and epidemiologic initiatives. The survey was distributed electronically on October 15, 2003, to each identified Focus Area B leader (N = 58) in each jurisdiction awarded resources under this cooperative agreement. The survey was also e-mailed to all 50 state epidemiologists to gather information from the four states without an identified Focus Area B leader, as well as to gain additional perspectives from others who might be involved in state-level syndromic surveillance activities. Responses were requested by October 21, 2003, to provide preliminary data for the National Syndromic Surveillance Conference at the New York Academy of Medicine on October 24, 2003. Statistical AnalysisThe survey design provided nine categorical questions with open-ended response options allowing for anecdotal remarks. Two investigators coded each response. If classification of a given response was questionable, the investigators evaluated the response separately and then compared results. In the event of a disparity, a third party evaluated the response and determined its final category. All analyses were performed by using data exported to S-PLUS® 2000 statistical software (5). Because the sampling frame was primarily intended to be the recipients of CDC terrorism-preparedness cooperative agreements (50 states, four localities, and eight territories), the most relevant response rate seemed to be the percentage of grantees who had a syndromic surveillance system either under development or in operation. However, the denominator for that rate was unknown, because the total number of CDC terrorism-preparedness grantees that already had or were developing a syndromic system was not known. To estimate that denominator, knowledgeable consultants (two terrorism consultants from the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists and a CDC surveillance program staff member) were asked to help generate a list of known states with such systems. The resulting estimate of 40 states, localities, and territories with syndromic surveillance systems (either under development or in operation) provided the denominator used to determine the survey coverage rate. ResultsOf the 48 Focus Area B leaders who received the survey, as verified by documented successful transmission of the e-mail, 33 responses were received from 32 states, cities, and counties and one territory (Table). Of the 32 responses from states, cities, and counties, two states reported a state-level perspective along with a city-level perspective from a jurisdiction performing a pilot project. One state provided three separate county-level perspectives reflecting three distinct syndromic surveillance projects; these were combined with the state response to form a single response for each state when tabulating the coverage rate. Thus, total responses from the 62 states, localities, and territories with CDC terrorism-preparedness cooperative agreements were 29. Because not all states, localities, or territories have active syndromic surveillance systems, the consensus estimate of the total state, locality, and territory grantees with active syndromic systems was 40, which yields a coverage rate for this survey of 74.4%. Each respondent was given the option to report anonymously or be identified by jurisdiction. Of the 33 responses received, a majority of respondents (54.6%) requested anonymity in reporting. To capture the nature of the responses to each question, examples are provided here. Responses to specific questions often addressed additional concerns to those raised by that question; to avoid subjectively imposing the investigators' views, such responses are reported here in conjunction with the question with which they initially appeared, even if the response seemed more relevant to another question. When compared with those respondents who identified "no problems" in the implementation of a syndromic surveillance system, more than one half (54.2%) reported either "some" or "substantial" problems caused by real or perceived patient-confidentiality concerns and HIPAA Privacy Rule requirements. For example, one respondent stated, "Even our routine investigations encounter roadblocks. Many people in the trenches don't know enough about HIPAA and do not give information beyond the minimum necessary. This hampers all disease surveillance activities." Another reported, "Almost every hospital we approached raised issues of compliance with HIPAA. Discussions led to what is a minimum data set." Of those respondents who indicated "no problems" in the implementation, responses included the following: "Our syndromic surveillance system collects aggregate data, so this has not been as much of an issue for us as it has been for many other states. In fact, of the more than 600 sites participating in our syndromic surveillance system last year, less than two dozen commented or asked about confidentiality concerns and HIPAA requirements." One survey question asked whether any concerns had arisen from the perception that syndromic reporting is not the same as disease reporting and might not be mandated by state statute. A similar percentage of respondents reported that such concerns were present (51.5%) or nonexistent (45.5%). Concerns included the following: "As we create more and more notifiable disease conditions, the medical community is increasingly resistant to accept without question." The question of whether syndromic surveillance was legally mandated yielded such responses as, "Reporting of diseases was both mandated and considered to be a more accurate surveillance tool, which caused many to feel it was unnecessary to ask people to also report syndromic information." Respondents were then asked whether they had considered adding syndromic surveillance indicators to state reporting statutes. A majority (66.7%) indicated this was not being considered. Among the rationales given was that adding syndromic surveillance to a mandated reporting list would be problematic because generally accepted methods and content for syndromic surveillance systems have not yet been established and because its effectiveness is still in question. Of respondents who reported that adding syndromic surveillance indicators was not being considered, 33% indicated that until clearer indicators are identified, the use of currently mandated reporting of clinical criteria (e.g., "clusters of extraordinary occurrence of illness" and "clusters of unusual illness") could apply to syndromic surveillance indicators. In addition, 54% of state-level respondents noted that, in the event of a recognized threat, their state health director is authorized to request that syndromic surveillance be conducted for a renewable period of time on the basis of an identified clinical presentation (e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS]). The survey also asked whether the HIPAA Privacy Rule requirement to account for disclosures to public health agencies was an obstacle to conducting syndromic surveillance. Of those responding, 22.6% reported concerns originating from this requirement. A majority of respondents indicated that their data were exchanged in limited data sets or aggregate form (e.g., emergency department [ED] visits or admission numbers), which do not require an accounting of disclosures. Twenty-three percent of respondents replied that the accounting requirement would be a concern if more detailed data were to be obtained. One respondent's jurisdiction had decided to collect only a limited data set, partly because of patient confidentiality concerns, and partly because the jurisdiction "rarely identified notifiable conditions via syndromic surveillance, and would end up having to call the hospital back for patient follow-up." Respondents expressed concerns about their syndromic surveillance system's ability to provide meaningful data when using only a limited data set. "Providers are cautious and it is not clear what we could provide to reassure them that a general accounting rather than transaction-specific accounting would work." The burden on local health departments of investigating signals generated by syndromic surveillance systems was also explored. A majority of respondents (56.7%) indicated that, in cases where signals were identified, facility staff did not raise concerns about cost or feasibility. However, 43.3% of respondents reported concerns regarding the investigation of a signal. Responses included the following: "Since we are no longer collecting patient identifiers, the only way we can follow up with hospitals is by asking them to trace back the patient(s) who were seen at the date(s) and time(s) of interest. Perhaps because we rarely make such requests, we have not had problems with compliance." The benefit of collecting individual patient records was evident from five respondents, who reported that the investigation of signals quickly showed that individually identifiable patient records are needed to trace information. As one respondent indicated, "We now have these and it is an immense improvement, saving considerable time for both investigators and providers." The survey also asked whether providers feared participation in syndromic surveillance would harm their public perception or increase their vulnerability to a terrorist attack. All respondents indicated that providers had a positive outlook towards participating in syndromic surveillance. A total of 30% noted that they enhance community security by looking for unusual patterns that might not normally be observed. The majority of states reported that their hospital staff view participation in syndromic surveillance positively and as an indication of readiness. One state respondent indicated that staff at certain health-care facilities view syndromic surveillance as helping them meet internal requirements. One respondent reported, "Most of our hospitals want to participate and say it is helpful for them to see a summary of who has been to the ED the previous day." Two survey questions examined concerns regarding the costs of syndromic surveillance. In the first question, a majority of respondents (65.6%) reported no issues associated with providers' costs of providing data. Thirty-seven percent of respondents identified initial problems regarding cost and have taken steps to reduce the burden on health-care facilities, including applying for federal grants for rural facilities and providing computers and Internet service by contracting with the facilities for data access and programmer time. Twenty-one percent reported using resources from the CDC terrorism-preparedness cooperative agreements and the Health Resource Services Administration (HRSA) Bioterrorism Hospital Preparedness Program for these activities. However, 14% expressed concern about setting a precedent of paying hospitals for their participation in the syndromic surveillance system. Certain respondents also acknowledged that not assisting hospitals with implementation might place an undue burden on facilities that do not have the information technology (IT) capacity to provide needed data. A total of 21% are establishing stipends to compensate hospital's IT departments for expenses incurred on behalf of their participation. Of those states that reported an active syndromic surveillance system (n = 16), 54% require the hospital to cover the costs of participation, whereas 45% either pay for initial costs outright or share costs with health-care facilities. The majority of respondents recommended federal sources for covering the costs of program initiation. The survey's final question addressed concerns about the security of data once they arrive at the health department. A substantial majority (84.4%) of respondents reported no security concerns from syndromic surveillance system participants, in part because of measures taken to ensure secure transmission (e.g., virtual private networks from a secure state file transfer protocol (FTP) site to the data sources) and off-system data-archiving protocols. For those collecting data without name-specific or identifiable data, security was of little concern to source participants. DiscussionThis was the first known survey on this topic targeted to state terrorism-preparedness managers and state epidemiologists. The survey attempted to assess the effect of the HIPAA Privacy Rule on the implementation of syndromic surveillance systems. Weaknesses of this survey include the limited response rate, the uncertain representativeness of the 33 responding jurisdictions (28 state or city and one territory cooperative-agreement recipients), and the limited time allotted for respondents to poll staff about problems with confidentiality or data access. Denominator data to account for all syndromic surveillance systems in the United States are difficult to quantify; therefore, the denominator estimate might not be accurate. The study is based on qualitative judgments of senior managers responsible for syndromic surveillance systems, many of which were initiated by using CDC funding. However, substantial attempts were made to notify Focus Area B leaders and state epidemiologists for all states and terrorism-preparedness--funded localities to act as an information-gathering conduit for this survey. The state points-of-contact are likely to be closely involved with development of syndromic surveillance systems, on the basis of their involvement in implementing routine disease surveillance systems and the initiatives supported by CDC terrorism-preparedness grants. Accordingly, the authors believe that few managers of large syndromic surveillance systems were unaware of the survey. As the only known attempt to gather representative data on these issues, this study provided new information on matters of importance and identified areas for future research. Ten percent of survey respondents also indicated that they request only limited data sets to more easily obtain permission and participation from covered entities. This can result in delays in investigating signals and, in certain cases, outright refusals of access to data on patient visits generating the signals. When signal investigations are substantially delayed, the syndromic surveillance system's value decreases. The added burden of retracing data to determine a signal's origin might hinder a timely response to an emerging situation. One source of covered entities' reported reluctance to provide data appears to be the perceived requirement that they account for all disclosures for public health purposes under the Privacy Rule; this concern was reported by 22.6% of respondents. This problem persists despite favorable interpretations on the use of simplified "routine accounting" processes under the Rule, as discussed in CDC guidance and through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Civil Rights (OCR). Respondents from two states indicated that attorneys or risk managers for health departments and certain covered entities do not deem OCR authoritative enough to require a change in their data-release policies. In addition, perception about the scope of HIPAA was reported to be a substantial source of concern to state and local participants at the National Center for Vital and Health Statistics Privacy Subcommittee's hearings on the impact of the HIPAA Privacy Rule on public health (6). Incorrect interpretations of health departments' existing legal authority and the HIPAA Privacy Rule might cause substantial delays, extra work, and obstacles to obtaining necessary data for various surveillance systems, including syndromic surveillance. OCR should disseminate clearer statements detailing how covered entities can use simplified accounting methods for routine disclosures to public health agencies and their contractual partners, pursuant to syndromic surveillance reporting requirements. The narrow perception of the accounting requirement and the view that it places an intolerable burden on covered entities might negatively impact the performance of syndromic surveillance systems within the United States, while accomplishing little to protect individual privacy where the existence of the disclosures underlying these public health practices are readily known. References

Table  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 9/14/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 9/14/2004

|