|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Community Interventions to Promote Healthy Social Environments: Early Childhood Development and Family HousingA Report on Recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive ServicesPrepared by Laurie M. Anderson, Ph.D., M.P.H., Carolynne Shinn, M.S., Joseph St. Charles,

M.P.A. in collaboration with Mindy T. Fullilove, M.D. Summary The sociocultural environment exerts a fundamental influence on health. Interventions to improve education, housing, employment, and access to health care contribute to healthy and safe environments and improved community health. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services (the Task Force) has conducted systematic reviews of early childhood development interventions and family housing interventions. The topics selected provide a unique, albeit small, beginning of the review of evidence that interventions do effectively address sociocultural factors that influence health. Based on these reviews, the Task Force strongly recommends publicly funded, center-based, comprehensive early childhood development programs for low-income children aged 3--5 years. The basis for the recommendation is evidence of effectiveness in preventing developmental delay, assessed by improvements in grade retention and placement in special education. The Task Force also recommends housing subsidy programs for low-income families, which provide rental vouchers for use in the private housing market and allow families choice in residential location. This recommendation is based on outcomes of improved neighborhood safety and families' reduced exposure to violence. The Task Force concludes that insufficient evidence is available on which to base a recommendation for or against creation of mixed-income housing developments that provide safe and affordable housing in neighborhoods with adequate goods and services. This report provides additional information regarding these recommendations, briefly describes how the reviews were conducted, and discusses implications for applying the interventions locally. BackgroundSociocultural factors are important determinants of health (1--3). Sociocultural determinants of health include societal resources (e.g., social institutions, economic systems, political structures), physical surroundings (e.g., neighborhoods, workplaces, built environments), and social relationships (4). Recognition that health is a product of social conditions facilitates identification of social determinants that might be amenable to community interventions that can lead to improved health outcomes. These interventions might also reduce the persistent disparities in health related to socioeconomic status, education, and housing. Early Childhood DevelopmentChild development is a powerful determinant of health in adult life as indicated by the strong relationship between measures of educational attainment and adult disease (5). The period of child development from birth to age 5 years is critical for normal brain development and establishment of a foundation for adult cognitive and emotional function (6). In addition to frequently cited risk factors for developmental dysfunction (e.g., premature birth, low birth weight, sequelae of childhood infections, and lead poisoning), exposure to an impoverished environment is recognized as a sociocultural risk factor (6,7). Because access to resources mediates the effects of adverse sociocultural conditions, children in poverty are especially vulnerable (7). Poverty in the United States is highest among children. Despite periodic declines in child poverty during the last 40 years, the rate increased from 17.6% to 19.7% during 1966--1997 (8). Low socioeconomic status during childhood interferes with cognitive and behavioral development and is a modifiable risk factor for lack of readiness for school (9). Head Start (a national preschool education program designed to prepare children from disadvantaged backgrounds for entrance into formal education in the primary grades) is an example of a feasible program that could diminish harm to young children from disadvantaged environments (10). Housing and HealthThe social, physical, and economic characteristics of neighborhoods also are increasingly recognized as having both short- and long-term consequences for residents' quality and years of healthy life (11,12). Among the most prevalent community health concerns related to family housing are the inadequate supply of affordable housing for low-income persons and the increasing spatial segregation of households by income, race, ethnicity, or social class into unsafe neighborhoods (13). The increasing concentration of poverty can result in physical and social deterioration of neighborhoods as indicated by housing disinvestment and deteriorated physical conditions and a reduction in the ability of formal and informal institutions to maintain public order. The ability of informal networks to disseminate information regarding employment opportunities and available health resources and promote healthy behaviors and positive life choices might decline as well (14). When affordable housing is unavailable to low-income households, family resources needed for food, medical or dental care, and other necessities are diverted to housing costs. Residential instability results, as families are forced to move frequently, live with other families in overcrowded conditions, or experience periods of homelessness. Residential instability is associated with children's poor attendance and performance in school, no primary source of medical care, lack of preventive health services (e.g., child immunizations), various acute and chronic medical conditions, sexual assault, and violence (15,16). Various policies and programs are available to improve community health outcomes. Two such programs were reviewed: the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Section 8 Housing Voucher Program and the creation of mixed-income housing developments. IntroductionThis MMWR report is one in a series of topics to be completed for the Guide to Community Preventive Services (the Community Guide), a resource that will include multiple chapters, each focusing on a preventive health topic. This report provides an overview of the process used by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services (the Task Force) to select and review evidence and summarizes the recommendations of the Task Force regarding community interventions that promote healthy social environments. A full report of the recommendations, supporting evidence (i.e., applicability, additional benefits, potential harms, barriers to implementation), cost-effectiveness of the interventions (where available), and remaining research questions will be published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine later this year. The independent, nonfederal Task Force is developing the Community Guide with the support of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) in collaboration with public and private partners. CDC provides staff support to the Task Force for development of the Community Guide. However, the recommendations presented in this report were developed by the Task Force and are not necessarily the recommendations of CDC or DHHS. MethodsThe Community Guide's methods for conducting systematic reviews and linking evidence to recommendations have been described elsewhere (17). In brief, for each Community Guide topic, a multidisciplinary team conducts reviews by

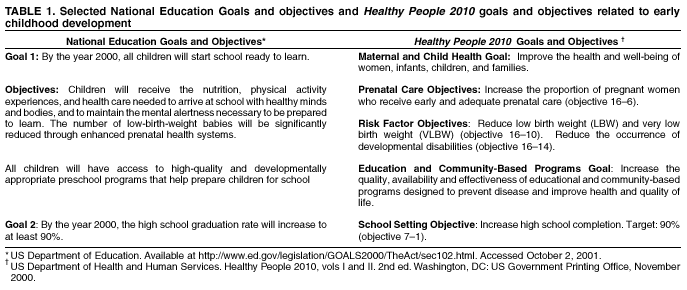

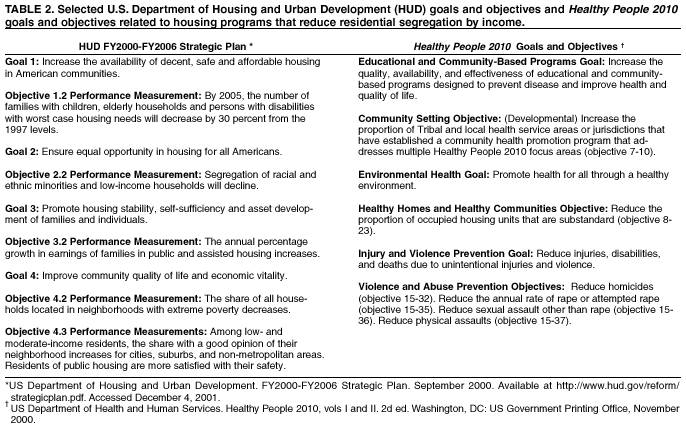

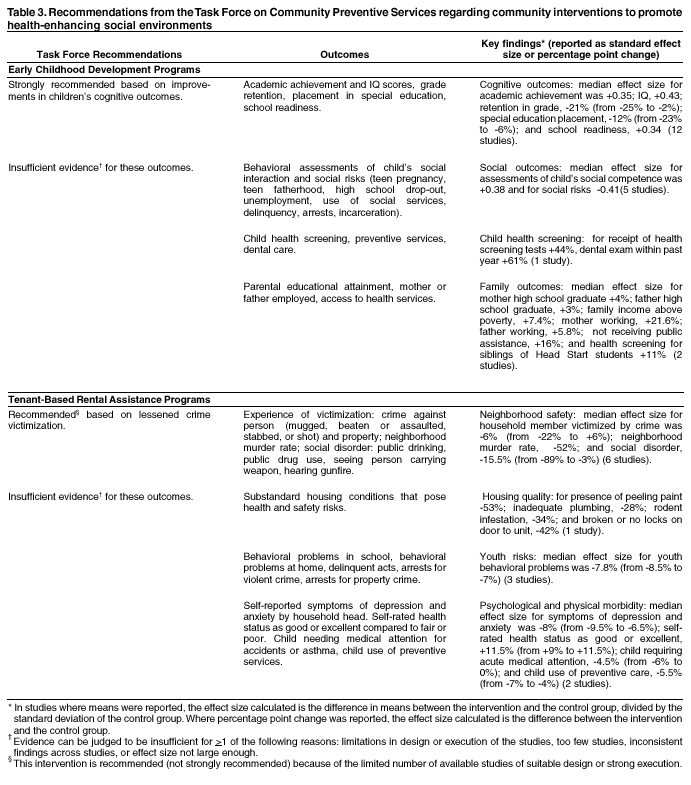

For this report, a multidisciplinary review team (the team) consisting of a coordination team (the authors) and a consultation team* developed a conceptual framework that identifies determinants of health in the social environment, health outcomes influenced by those determinants, and points between determinants and outcomes where community interventions might have positive effects. After polling consultants and other specialists in the field regarding the importance of various interventions for improving the health of communities, the review team created an extensive list of interventions and subsequently created a priority list of interventions for review. For early childhood development, the team focused on publicly funded, center-based, comprehensive preschool programs designed to promote the cognitive and social development of children aged 3--5 years at risk because of poverty. To be included in the reviews of effectiveness, studies had to a) document an evaluation of an early childhood development program within the United States; b) be published in English since 1965; c) compare outcomes among groups of persons exposed to the intervention with outcomes among groups of persons not exposed to the intervention (whether the comparison was concurrent between groups or before-after within groups); and d) report a relevant outcome measure. Relevant outcomes were a) cognitive (academic achievement, IQ scores, grade retention rates, placement in special education, and school readiness); b) social (child behavioral assessments, teen parenting, high school graduation, employment, use of social services, delinquency, arrests, and incarceration); c) health (health screening, preventive services, and dental care); d) family (parental educational attainment, employment of parents, family incomes above poverty level, receipt of public assistance, and siblings' use of preventive care). Included in this report are selected National Education Goals and Healthy People 2010 goals and objectives that highlight the intersection of health and cognitive outcomes related to early childhood development (Table 1). Selected goals and objectives from HUD and Healthy People 2010 related to housing programs that reduce residential segregation by income, race, or ethnicity are also included (Table 2). Among programs that provide families with affordable housing, the team selected for review, based on the priority-setting exercise described above, two that are intended to decrease residential segregation by socioeconomic status. The creation of mixed-income housing developments has potential as an effective method for increasing local socioeconomic heterogeneity and preventing or reversing neighborhood physical and social deterioration while expanding the supply of decent, affordable housing. Tenant-based rental assistance was selected as a method for providing housing assistance to low-income households by allowing assisted households choice in selecting private-market rental units in higher-income neighborhoods. To be included in the reviews of effectiveness, studies had to a) document an evaluation of a mixed-income housing development or a tenant-based rental voucher program for families within the United States; b) be published in English since 1965; c) compare outcomes among groups of persons exposed to the intervention with outcomes among groups of persons not exposed to the intervention (whether the comparison was concurrent between groups or before-after within groups); and d) report a relevant outcome measure. Relevant outcomes were a) housing hazards (substandard housing conditions that pose health and safety risks); b) neighborhood safety (intentional injuries, victimization from crime, crime against person and property, and social disorder); c) youth risk behaviors (behavioral problems in school and at home, dropping out of school, delinquency, and arrests); d) mental or physical health status (physical or psychological morbidity and unintentional injury). To ascertain implementation of the program, data were also collected regarding the percentage of household income spent on housing and on socioeconomic heterogeneity of housing development residents (for mixed-income housing developments) or of neighborhood (for rental voucher programs). For each intervention reviewed, the team developed an analytic framework indicating possible causal links between the intervention studied and the predetermined outcomes of interest. Outcomes of interest for early childhood development programs were gains in intellectual ability, social cognition, social and health risk behaviors (e.g., disruptive behavior in school, school drop-out, substance abuse, teen pregnancy), use of preventative services (e.g., immunizations, health screenings, and dental exams), and family's use of health promotion programs. Outcomes of interest for housing interventions were housing hazards (e.g., peeling lead paint, mold, rodent infestation), neighborhood safety and physical disorder (e.g., crime, victimization, public drinking or drug use, abandoned buildings, trash), social isolation, and social and health risks (e.g., unemployment, school drop-out rates, measures of mental and physical health status). To make a recommendation, the Task Force required a sufficient number of studies, a consistent effect, and a sufficient effect size for at least one outcome (either a health outcome or a more proximal outcome closely linked to a health outcome) (17). For early childhood development programs, searches were conducted in five computerized databases --- PsychInfo, Educational Resource Information Center (ERIC), Medline, Social Science Search, and the Head Start Bureau research database.† Published annotated bibliographies on Head Start and other early childhood development research, reference lists of reviewed articles, meta-analyses, and Internet resources were also examined, as were referrals from specialists in the field. For family housing programs, searches were conducted in ten computerized databases --- Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals, EBSCO Information Services' Academic Search™ Elite, HUD User Bibliographic Database, MarciveWeb Catalogue of U.S. Government Publications, ProQuest Dissertations, ProQuest General Research Databases, PsychInfo, Public Affairs Information Services, Social Sciences Citation Index, and Sociological Abstracts.§ Internet resources were examined, as were reference lists of reviewed articles and referrals from specialists in the field. Each study that met the inclusion criteria was evaluated using a standardized abstraction form and assessed for suitability of the study design and threats to validity (18). On the basis of the number of threats to validity, studies were characterized as having good, fair, or limited execution. Results on each outcome of interest were obtained from each study that met the minimum quality criteria. Where possible, for studies that reported multiple measures of a given outcome, the "best" measure with respect to validity and reliability was chosen according to consistently applied rules. Measures that were adjusted for the effects of potential confounders were used in preference to crude effect measures. For studies in which adjusted results were not provided, net effects were derived when possible by calculating the difference between the changes observed in the intervention and comparison groups. Among similar effect measures, the median was calculated as a summary measure. The strength of the body of evidence of effectiveness was characterized as strong, sufficient, or insufficient on the basis of the number of available studies, the suitability of study designs for evaluating effectiveness, the quality of execution of the studies, the consistency of the results, and the effect size (17). The Task Force recognizes that a body of relevant social science literature was excluded from the reviews of effectiveness reported here because it lacked relevant comparisons. The excluded literature is rich and valuable for several purposes, such as assessing the need for programs, generating hypotheses, describing programs, assessing the fidelity with which programs were implemented, and many others. However, the Task Force thought this literature was less reliable for attributing effects to programmatic efforts and it was therefore not the primary focus of this review. Nonetheless, considerable use of the excluded literature in choosing topics, developing logic and analytic frameworks, and providing implementation advice has been made. The Task Force makes recommendations based on the findings of the systematic reviews. The strength of each recommendation is based on the strength of the evidence of effectiveness (e.g., an intervention is strongly recommended when strong evidence of effectiveness exists, and an intervention is recommended when sufficient evidence exists) (17). Other types of evidence can also affect a recommendation. For example, evidence of harms resulting from an intervention might lead to a recommendation that the intervention not be used if adverse effects outweigh improved outcomes. A finding of insufficient evidence of effectiveness does not result in recommendations for or against an intervention's use, but is important for identifying areas of uncertainty and research needs. In contrast, sufficient or strong evidence of ineffectiveness leads to a recommendation that the intervention not be used. ResultsFor early childhood development, the literature search yielded a list of 2,100 articles, of which 350 were assessed for inclusion. A total of 57 articles meeting the inclusion criteria (i.e., studied a relevant intervention, had a comparative study design, and reported on one or more outcomes relevant to the early childhood development analytic framework) was obtained and evaluated. Of these, 40 were excluded on the basis of threats to validity or because they duplicated information provided in another included study. The remaining 17 studies were considered qualifying studies on which the Task Force recommendation is based. All of the qualifying studies had good or fair quality of execution. The Task Force strongly recommends publicly funded, center-based, comprehensive early childhood development programs for children aged 3--5 years, at risk because of poverty, on the basis of the strong evidence of effectiveness for improving cognitive outcomes of grade retention and placement in special education (Table 3). Although the Task Force made no recommendation based on other outcomes, members noted the remarkable and positive long-term effects (e.g., reduced teen pregnancy, completion of high school, employment, home ownership, and reduced arrests and incarceration) from the High/Scope Perry Preschool Program (19). However, this intervention differed from other early childhood development programs in terms of quality and implementation support, and results could not be generalized to other programs such as Head Start. For the review of mixed-income housing developments, the review team examined 312 citations (titles and abstracts) identified through the database search, review of pertinent reference lists, and consultation with housing specialists. A total of 41 articles, reports, and dissertations were obtained, but none met the inclusion criteria (i.e., studied a relevant intervention, had a comparative study design, and reported on one or more outcomes relevant to the analytic framework). As a result, insufficient evidence existed on which the Task Force could base a recommendation for or against the use of this intervention. This lack of evidence does not mean that this intervention is ineffective, but does indicate the need for well-designed evaluations of such interventions, which would allow assessment of their effectiveness. For the review of tenant-based rental voucher programs, the literature searches yielded 509 citations, of which 56 were obtained and evaluated for inclusion based on a relevant intervention, a comparative study design, and a report of relevant outcomes. A total of 23 articles and reports qualified for evidence review. Based on consistency of effect and sufficient effect size, the Task Force recommends the use of rental voucher programs to improve household safety by providing families choice in moving to neighborhoods with reduced exposure to violence (Table 3). Use of the Recommendations in CommunitiesInterventions that improve children's opportunities to learn and develop capacity should be relevant to all communities. These interventions are particularly important for children in communities with high rates of poverty, violence, substance abuse, and physical and social disorder. Children with multiple risks benefit most from early childhood development interventions (20). Communities can assess the quality and availability of center-based early childhood development programs in terms of local needs and resources and can use the Task Force recommendation to advocate for continued or expanded funding of early childhood development programs. Current levels of federal and state funding are not adequate to support accessible quality services for the number of children at risk who would benefit from participation (21). The Task Force recommendation can be used as the evidence of effectiveness for those making policy and funding decisions. Health-care providers can use the recommendation to promote participation in an early childhood development program as part of well-child care. Public health agencies can use the Task Force recommendation to inform the community regarding the importance of early childhood development opportunities and their long-lasting effects on a child's well-being and ability to learn. It is beyond the scope of this report to provide "how to" advice on implementing these programs. However, such advice is available through other early childhood development studies and entities (22). Given the complexities of human development, no single intervention is likely to protect a child completely or permanently from the effects of harmful exposures, preintervention or postintervention. We expect that these interventions will be most useful and effective as part of a coordinated system of supportive services for families (e.g., child care, housing and transportation assistance, nutritional support, employment opportunities, and health care) (23). Grassroots organizations, community advocacy groups, and resident stakeholders are in key positions to assess affordable housing needs within their own communities. Public housing assistance does not reach a large proportion of low-income families (24). An ongoing statewide assessment of housing affordability, availability, and quality can provide data for community organizations, elected officials, policy makers, and public agencies to stimulate the development of resources to meet local needs. The Task Force recommendation can be used by public health agencies in conjunction with local housing authorities to inform policy makers of the effectiveness of rental voucher programs for increasing family safety in the neighborhood environment. The recommendations could serve as an impetus for local health departments, which provide families with comprehensive services, to assess and monitor the effects of housing conditions on health. Working with public health and local housing agencies, community-based housing advocates and urban planning and community development groups can advocate for continued and expanded funding for housing resources adequate to sustain family safety and residential stability and thus support a healthy community. Additional Information Regarding the Community GuideCommunity Guide topics are prepared and released as each is completed. Previously released reviews and recommendations cover population-based interventions to improve vaccination coverage and oral health, reduce tobacco use, reduce injuries to motor-vehicle occupants, improve the health and longevity of persons with diabetes, and increase physical activity. A compilation of systematic reviews will be published in book form. Additional information regarding the Task Force, the Community Guide, and a list of published articles is available on the Internet at http://www.thecommunityguide.org. References

* Members of the consultation team were Regina M. Benjamin, M.D., M.B.A., Bayou La Batre Rural Health Clinic, Bayou La Batre, Alabama; David Chavis, Ph.D., Association for the Study and Development of Community, Gaithersburg, Maryland; Shelly Cooper-Ashford, Center for Multicultural Health, Seattle, Washington; Leonard J. Duhl, M.D., School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, California; Ruth Enid-Zambrana, Ph.D., Department of Women's Studies, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland; Stephen B. Fawcette, Ph.D., Work Group on Health Promotion and Community Development, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas; Nicholas Freudenberg, Dr.P.H., Urban Public Health, Hunter College, City University of New York, New York, New York; Douglas Greenwell, Ph.D., The Atlanta Project, Atlanta, Georgia; Robert A. Hahn, Ph.D., M.P.H., Epidemiology Program Office, CDC, Atlanta, Georgia; Camara P. Jones, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, Atlanta, Georgia; Joan Kraft, Ph.D., National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, Atlanta, Georgia; Nancy Krieger, Ph.D., School of Public Health, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Robert S. Lawrence, M.D., Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; David V. McQueen, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, Atlanta, Georgia; Jesus Ramirez-Valles, Ph.D., M.P.H., School of Public Health, University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois; Robert Sampson, Ph.D., Social Sciences Division, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois; Leonard S. Syme, Ph.D., School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, California; David R. Williams, Ph.D., Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. † These databases can be accessed as follows: PsychInfo: DIALOG, http://dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://www.apa.org/psycinfo/products/psycinfo.html; ERIC: http://www.askeric.org/Eric/; Medline: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed/; SocSci Search: DIALOG http://dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account); http://www.isinet.com/isi/products/citation/ssci/index.html; Head Start Bureau: http://www2.acf.dhhs.gov/programs/hsb/. § These databases can be accessed as follows: Avery Index: DIALOG http://dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://www.columbia.edu/cu/libraries/indexes/avery-index.html; EBSCO: GALILEO http://galileo.gsu.edu (requires id/password), http://www.epnet.com/database.html#af; HUD User Bibliographic Database: http://www.huduser.org/bibliodb/pdrbibdb.html; MarciveWeb Catalogue: http://www.marcive.com/HOMEPAGE/web7.htm; ProQuest Dissertations: http://wwwlib.umi.com/dissertations/; ProQuest General Research: http://www.proquest.com/proquest/; PsychInfo: DIALOG, http://dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://www.apa.org/psycinfo/products/psycinfo.html; Public Affairs Information Services: DIALOG, http://dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://www.pais.org/products/index.stm; Social Sciences Citation Index: DIALOG http://dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://www.isinet.com/isi/products/citation/ssci/index.html; Sociological Abstracts: DIALOG http://dialogclassic.com (requires id/password account), http://www.csa.com/detailsV5/socioabs.html. Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Table 3  Return to top. Task Force On Community Preventive Services* Chair: Jonathan E. Fielding, M.D., M.P.H, M.B.A., Los Angeles Department of Health Services, Los Angeles, California Vice-Chair: Patricia Dolan Mullen, Dr.P.H., University of Texas-Houston, School of Public Health, Houston, Texas Members: Ross C. Brownson, Ph.D., St. Louis University School of Public Health, St. Louis, Missouri; Mindy Thompson Fullilove, M.D., New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University, New York, New York; Fernando A. Guerra, M.D., M.P.H., San Antonio Metropolitan Health District, San Antonio, Texas; Alan R. Hinman, M.D., M.P.H., Task Force for Child Survival and Development, Atlanta, Georgia; George J. Isham, M.D., HealthPartners, Minneapolis, Minnesota; Garland H. Land, M.P.H., Center for Health Information Management and Epidemiology, Missouri Department of Health, Jefferson City, Missouri; Charles S. Mahan, M.D., College of Public Health, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida; Patricia A. Nolan, M.D., M.P.H., Rhode Island Department of Health, Providence, Rhode Island; Susan C. Scrimshaw, Ph.D., School of Public Health, University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois; Steven M. Teutsch, M.D., M.P.H., Merck & Company, Inc., West Point, Pennsylvania; Robert S. Thompson, M.D., Department of Preventive Care, Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Seattle, Washington Consultants: Robert S. Lawrence, M.D., Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; J. Michael McGinnis, M.D., Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, New Jersey; Lloyd F. Novick, M.D., M.P.H., Onondaga County Department of Health, Syracuse, New York * Patricia A. Buffler, PhD., M.P.H., University of California, Berkeley; Mary Jane England, M.D., Regis College, Weston, Massachusetts; Caswell A. Evans, Jr., D.D.S., M.P.H., National Oral Health Initiative, Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, Rockville, Maryland; and David W. Fleming, M.D., CDC, Atlanta, Georgia, also served on the Task Force while the recommendations were being developed.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 1/30/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 1/30/2002

|