|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

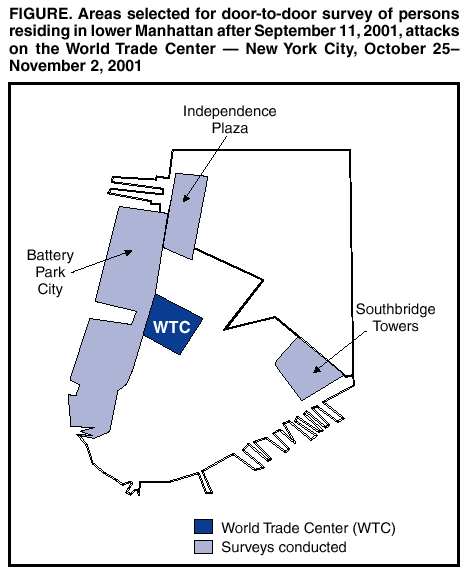

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Community Needs Assessment of Lower Manhattan Residents Following the World Trade Center Attacks --- Manhattan, New York City, 2001On September 11, 2001, terrorists attacked and destroyed the World Trade Center (WTC) in New York City (NYC). An estimated 2,819 persons were reported killed in the attacks; many others were injured (Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene [NYCDOHMH], unpublished data, 2002). An estimated 25,000 persons living nearby in lower Manhattan were affected both physically and emotionally. Many persons witnessed the attacks; lost family and friends; were exposed to smoke, dust, and debris; and evacuated their homes. To identify the health-related needs and concerns of persons residing near the attack site, NYCDOHMH, in collaboration with CDC, surveyed persons residing in areas immediately surrounding the WTC site. The primary purpose of the survey was to gather information to set priorities and direct public health interventions. This report summarizes findings from the assessment, which indicate that a large proportion of respondents had physical and psychological symptoms potentially associated with the exposure and needed information to address their health and safety concerns. On the basis of the results of the survey, NYCDOHMH responded to resident concerns, helped reduce exposure to dust and debris, and provided information about mental health resources. The survey was conducted door-to-door in three residential areas in lower Manhattan: Battery Park City, Southbridge Towers, and Independence Plaza (populations: approximately 8,000, 2,000, and 2,300, respectively) (Figure). These areas represented compact, well-defined neighborhoods comprising approximately 50% of the residential population of lower Manhattan. On the basis of data from the NYC Department of City Planning and on information provided by building managers, a representative random sample of households were selected, yielding a final sample size of >100 households per area. Survey teams composed of NYCDOHMH and CDC staff interviewed one adult (i.e., person aged >18 years) in each household selected. A standardized questionnaire was developed to obtain information about household demographics, exposure to the WTC attack, physical and mental health status, access to services, and urgent needs and concerns. The questionnaire included the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) checklist, a validated 17-item screening instrument for symptoms of PTSD based closely on DSM-IV criteria (1). Data were analyzed using Epi-Info 6.04 and SAS 8.2. Data from the three surveyed areas were combined and weighted on the basis of the total number of occupied households in each neighborhood. With the assistance of building managers and staff, tenant associations, and other community organizations, survey teams succeeded in contacting 485 of 990 households that had been selected randomly. Uncontacted households included those that were not yet reoccupied and those whose residents were unavailable when visited. A total of 71 persons declined to participate; the overall participation rate was 85.4%. During October 25--November 2, 2001, a total of 414 surveys were completed, including 145 in Battery Park City, 157 at Southbridge Towers, and 112 at Independence Plaza. Overall, an estimated 75.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]=71.8%--78.4%) of households were evacuated after the attacks. Respondents had a median age of 45 years (range: 18--92 years), and 16.4% (95% CI=12.7%--20.1%) had children aged <18 years. An estimated 55.2% (95% CI=50.1%--60.4%) of the population witnessed the collapse of the WTC towers, 29.0% (95% CI=24.2%--33.7%) witnessed persons being injured or killed, and 48.1% (95% CI=42.9%--53.2%) knew someone who died as a result of the attacks. Although many households lost utility services (i.e., water, electricity, and gas) after September 11, almost all had functional services at the time of interview; however, some households still did not have telephone service (15.5%; 95% CI=12.1%--18.8%). Approximately half of the population reported feeling safe in their homes; those not feeling safe were most concerned about air quality and surface dust. Information about proper cleaning procedures was received by 61.2% (95% CI=56.3%--66.2%), and 45.2% (95% CI=39.9%--50.6%) reported that their apartments had been cleaned according to recommended methods of wet mopping hard surfaces and using high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter vacuums on carpeting. Residents also indicated a need for further information regarding exposure to dust and debris from the WTC and its effect on health, recommendations for proper clean up, and availability of both mental health and relief services. Symptoms reported most frequently that developed or increased after September 11 were nose or throat irritations (65.8%; 95% CI=60.9%--70.7), eye irritation or infection (49.7%; 95% CI=44.6%--54.9%), and coughing (46.5%; 95% CI=41.3%--51.6%). At the time of the interviews, these symptoms continued to be a problem among approximately 82% of the adult population. Few respondents reported lack of access to medical care (6.6%; 95% CI=4.1%--9.2%), yet 13.6% (95% CI=9.6%--17.5%) reported problems filling prescriptions, primarily because of problems with phones and transportation. When asked about symptoms of PTSD, an estimated 38.9% (95% CI=33.9%--44.0%) of the adult population scored above the screening cutoff of 43, indicating a need for further mental health evaluation and a potential for PTSD. An estimated 36.8% (95% CI=28.9%--44.7%) of this population had received some type of supportive counseling, compared with 22.7% (95% CI=16.9%--28.4%) of the population with scores below the cutoff. Overall, an estimated 28.1% (95% CI=23.4%--32.8%) of the adult population had received some type of supportive counseling. A total of 38.7% (95% CI=33.6%--43.9%) thought they would benefit from any or additional supportive counseling; of these, 34.0% (95% CI=25.8%--42.3%) reported not having adequate access to this kind of support. When asked about alcohol use, 14.0% (95% CI=10.2%--17.7%) reported having used alcohol more than they meant to since the attack, and 6.5% (95% CI=3.7%--9.2%) felt that they needed to decrease their drinking since the attack. On the basis of the survey results, NYCDOHMH initiated focused outreach in lower Manhattan neighborhoods through presentations with tenant associations and community groups to share information and provide a forum for questions and concerns. Materials were developed and disseminated regarding environmental issues and related health problems, current air and dust testing results and their implications, recommendations for cleaning up and reducing further exposures, psychological effects, and availability of relief services. Materials were distributed to residential buildings and community organizations, and were made available at public places (e.g., libraries, stores, and restaurants) and on NYCDOHMH's website (http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/pdf/chw/needs1.pdf). NYCDOHMH monitored efforts to maintain dust suppression in the areas close to the WTC site and communicated closely with other agencies overseeing the cleanup process around the site. The assessment findings also were shared with Project Liberty, a disaster recovery program funded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency that provides outreach, crisis counseling, and public education services to persons affected by the WTC disaster. Reported by: R Kramer, ScD, R Hayes, MA, V Nolan, MPH, S Cotenoff, JD, A Goodman, MD, New York City Dept of Health and Mental Health. WR Daley, DVM, C Rubin, DVM, A Henderson, PhD, WD Flanders, MD, National Center for Environmental Health; N Smith, PhD, EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:This community assessment documented the public health impact of the WTC attacks on persons living nearby in lower Manhattan. Although basic community services were available 6 weeks after the attacks, persistent physical and psychological symptoms were reported among local residents. Residents also expressed concern about air quality and potential short- and long-term health effects, especially after Environmental Protection Agency reports of the presence of asbestos, particulate matter, and volatile organic compounds at the WTC site. The high proportion of the local population that reported experiencing health problems potentially related to respiratory irritants supported this concern. As with other needs assessments conducted soon after a disaster (2,3), this survey provided systematically collected information that could be used to respond to public concerns and to address the health and mental health needs of this population. Although the air quality in lower Manhattan improved with time, resulting in a reduction of some of the immediate physical impact from the attacks, the psychological impact remained. The estimated proportion of residents with increased potential for PTSD is consistent with estimates of PTSD following other disasters (4,5). These estimates suggest that thousands of persons residing in lower Manhattan might have been at risk for PTSD and could potentially benefit from receiving supportive mental health services. A central component to outreach in this community involved education about the benefits and availability of supportive counseling services available through Project Liberty. The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, the survey did not include persons who had not yet returned to their homes. Those who delayed returning might have had more serious psychological or physical symptoms. Second, because the survey did not include this population, the estimates for the mean time of evacuation also are underestimated. Third, no background or comparison data were available to validate the self-reported assessment of health effects, and these assessments were not verified by health-care providers. Finally, the indicator of potential for PTSD was not diagnostic. In response to the assessment, NYCDOHMH conducted extensive outreach, developed and disseminated informational materials, and provided referral services to meet community needs. This assessment and its follow-up activities also provided an opportunity for persons living near the WTC site to voice their concerns to government agencies in the aftermath of the disaster. NYCDOHMH was able to provide an important service for this community by giving local residents timely and comprehensive information. Feedback received from residents highlights the need to conduct a community assessment as soon as possible after a disaster. Because the needs and health effects following a disaster often vary over time, multiple community assessments might be necessary to monitor these changes and to reach different populations if evacuations have occurred. The availability of standardized assessment tools and local health professionals trained in rapid needs assessment procedures could facilitate understanding a community's post-disaster needs. Acknowledgments This report is based on data contributed by the New York City Dept of City Planning; Community HealthWorks, New York City Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene. Lower Manhattan Community Assessment Team, CDC. References

Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 9/9/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 9/9/2002

|