|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

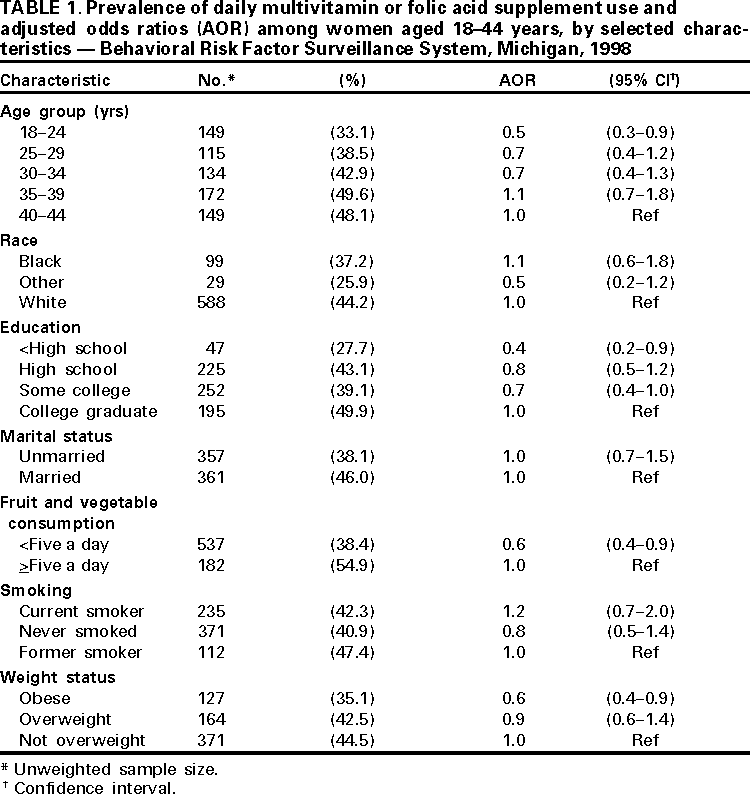

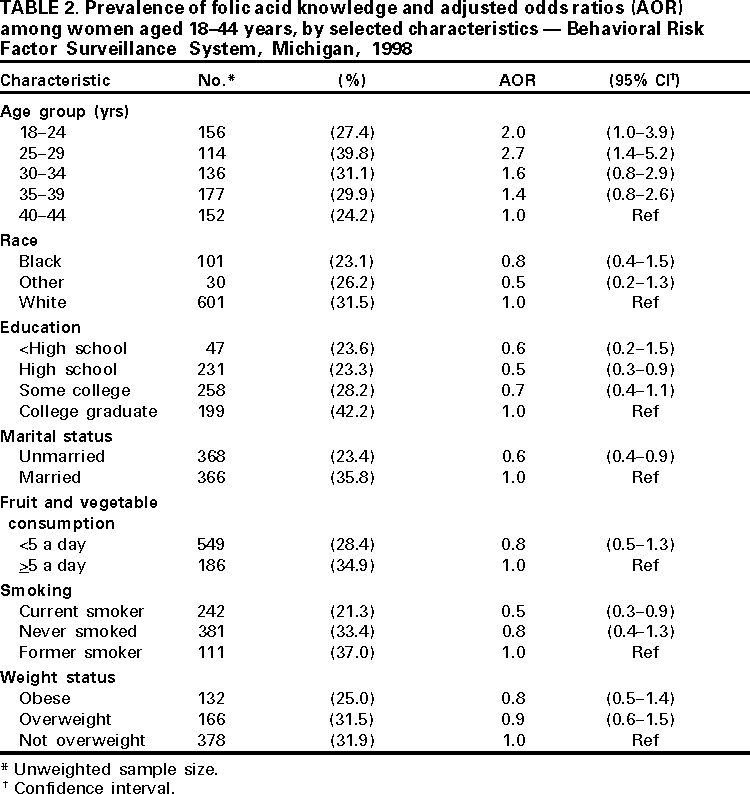

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Knowledge and Use of Folic Acid Among Women of Reproductive Age --- Michigan, 1998Neural tube defects (NTDs), which include spina bifida and anencephaly, are serious malformations that occur in the developing fetus during the first 17--30 days after conception (1). Consumption of supplements containing folic acid can reduce NTDs 50%--70% (2,3). In the United States, approximately 4000 pregnancies are affected by NTDs each year, including approximately 140 infants in Michigan. In 1992, the U.S. Public Health Service recommended that all women of childbearing age consume at least 400 µg of folic acid daily (4). In 1998, the Institute of Medicine reaffirmed that recommendation and added that women capable of becoming pregnant take 400 µg of synthetic folic acid daily from fortified foods and/or supplements and consume a balanced, healthy diet of folate-rich foods (5). This report summarizes findings from the 1998 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) about multivitamin use and folic acid knowledge among women of reproductive age in Michigan. The findings suggest that public health campaigns that promote the consumption of folic acid should target women who are young, unmarried, obese, smoke, eat few fruits and vegetables, and have a low level of education. BRFSS is an ongoing, state-based, random-digit--dialed telephone survey of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged >18 years (6). In 1998, 2613 persons were interviewed in Michigan. Analysis was restricted to 739 women of reproductive age (aged 18--44 years). Multivitamin use was defined as taking a folic acid-containing multivitamin or a folic acid supplement at least once a day. Knowledge of folic acid use was defined as having answered that the reason health experts recommend that women take folic acid was to prevent birth defects. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used to determine risk factors for multivitamin use and knowledge of folic acid. SUDAAN was used to account for the complex study design (6). Age, race, education, marital status, fruit and vegetable consumption, smoking, and weight status (overweight: body mass index [BMI] >25.0 kg/(height2)[in meters] <30.0 or obese: BMI >30.0 kg/[(height2]) were identified as variables of interest and included in the multivariable analysis. Overall, 42.4% of women reported taking a multivitamin or folic acid supplement daily. Multivitamin use increased with age, from 33.1% for women aged 18--24 years to 48.1% for women aged 40--44 years. The prevalence of women who used a multivitamin was highest among those who were consumers of five or more fruits and vegetables a day (54.9%), college educated (49.9%), aged 35--39 years (49.6%), former smokers (47.4%), married (46.0%), not overweight (44.5%), and white (44.2%) (Table 1). After multivariable analysis, the following groups were statistically significantly less likely than their respective comparison group to use a multivitamin daily: women aged 18--24 years, women who had a low level of education, women who ate less than five fruits and vegetables a day, and obese women. Overall, 30.0% of women had knowledge of folic acid use, defined as responding that the prevention of birth defects is the reason to take folic acid. The prevalence of women with folic acid knowledge was highest among women who were college graduates (42.2%), aged 25--29 years (39.8%), former smokers (37.0%), married (35.8%), ate five or more fruits and vegetables a day (34.9%), not overweight (31.9%), and white (31.5%) (Table 2). Multivariable analysis indicated that women who were high school graduates, current smokers, and unmarried were statistically significantly less likely than their respective comparison group to have correct knowledge of folic acid use. Women aged 18--29 were statistically significantly more likely than their respective comparison group to have correct knowledge. Reported by: M Reeves, A Rafferty, Bur of Epidemiology; JC Simmeron, J Bach, Michigan Birth Defects Registry, Michigan Dept of Community Health. State Br, Div of Applied Public Health Training, Epidemiology Program Office; Maternal and Child Health Br, Div of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; and an EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate that younger women, women with low education, women with low fruit and vegetable consumption, and obese women were associated with lower levels of reported multivitamin use. Being unmarried or a current smoker was associated with low folic acid knowledge, and having less education (an indicator of low socioeconomic status) was associated with both low levels of multivitamin use and low folic acid knowledge. Eating few fruits and vegetables and smoking also are correlated with socioeconomic status. Therefore, socioeconomic status is a marker for low folic acid knowledge and low multivitamin use in Michigan, as has been shown in previous studies (7). Because low education level was associated with low folic acid knowledge, a continued educational effort from medical and nutritional professionals is needed to increase knowledge and support behavior change (8). The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, because BRFSS excludes persons aged <18 years, folic acid knowledge and prevalence estimates do not represent the entire reproductive-aged population. Second, BRFSS excludes persons without telephones; therefore, data may underestimate the number of women of reproductive age from low socioeconomic groups. Third, the data are self-reported and the validity of the data is unknown. Finally, because the overall sample size is relatively small, some estimates are unreliable, as indicated by the wide confidence intervals. Through a 3-year cooperative agreement with CDC, the Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH) Division for Vital Records and Health Statistics and the Hereditary Disorders Program seek opportunities to increase awareness of NTD prevention through conferences, presentations, and the distribution of folic acid literature to public and professional audiences. The School Health Unit at MDCH also identifies opportunities for folic acid education in curricula developed for the Michigan Model for Comprehensive School Health Education, which reaches approximately 950,000 Michigan students and their families. Other organizations, such as the March of Dimes and the Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses are implementing folic acid campaigns and educational programs to help prevent NTDs in Michigan. The March of Dimes Greater Michigan Chapter has partnered with grocery stores in the Grand Rapids area to print folic acid messages on store grocery bags, and the Southeast Michigan Chapter has disseminated folic acid messages through public service announcements and partnerships with faith based organizations, corporations, representatives from the Arab and Hispanic communities, and professional medical groups. The public health community should continue to use multiple strategies to increase folic acid intake and consumption. The current level of folic acid in fortified food (140 µg per 100 g cereal grain product) is intended to increase a woman's intake by approximately 100 µg per day (9). Although the current levels of fortification may not be sufficient to provide the necessary dietary intake of folic acid for many women who become pregnant, fortification has had a substantial effect on increasing folate levels (10). Because approximately 50% of pregnancies are unplanned, all women of childbearing age should be encouraged to consume 400 µg of folic acid from fortified foods and/or supplements and to consume a balanced, healthy diet of folate-rich foods. References

Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 3/15/2001 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|