|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

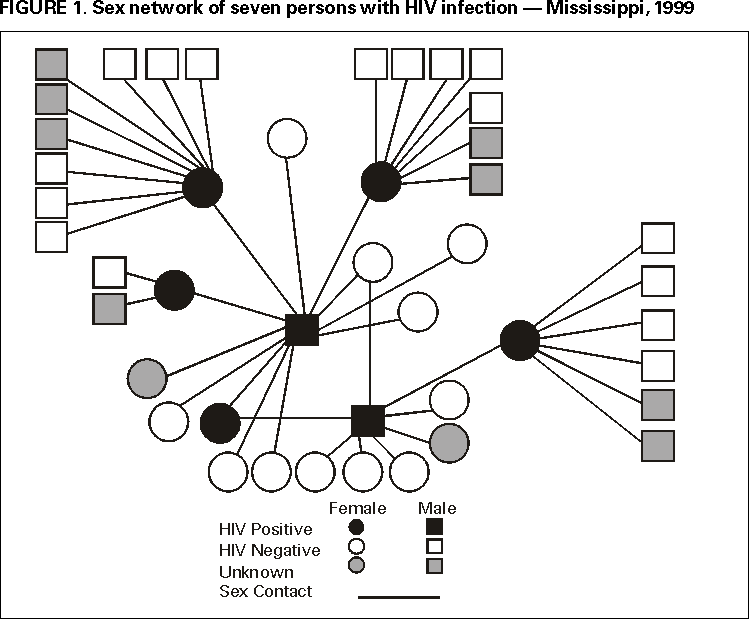

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Cluster of HIV-Infected Adolescents and Young Adults --- Mississippi, 1999From February through June 1999, seven human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected young persons were identified in a small town in rural Mississippi. Two persons were identified through routine voluntary HIV testing during sexually transmitted disease (STD) evaluations, and five were identified subsequently through contact investigation by the local health department. Contact investigation identified sex partners and social contacts (i.e., persons who shared social surroundings) and defined a social network of 122 sex and social contacts. Seven (9%) of 78 persons tested from the social network were HIV-infected. Within the social network, a sexual contact network of 44 persons (the seven HIV-infected persons and their sex partners) was identified. The Mississippi State Department of Health asked CDC to join the investigation to describe further the cluster and help direct prevention efforts. This report summarizes the investigation of this cluster and underscores the need for HIV prevention and treatment in rural areas. HIV-infected persons and uninfected sex partners were interviewed, and a case-control analysis was performed to assess risk factors for infection. Uninfected female social contacts who had not had sex with the infected men also were interviewed and compared with the HIV-infected women to assess risk factors for exposure. Kruskal-Wallis (KW) and Fischer exact (FE) statistical tests were used. For HIV-infected persons, sensitive-less sensitive detuned assays (1) were performed to identify persons probably infected within 180 days of diagnosis, and CD4+ cell counts and plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were measured to identify need for treatment. Questionnaires were mailed to local internists and family practitioners to establish HIV care patterns and practices in the area. Persons in the sex network (Figure 1) had a median age of 21 years (range: 13--45 years), and all were black. The network was located in an economically depressed neighborhood with few organized social activities. Interviews with the seven HIV-infected persons (five women) and 22 uninfected sex partners (10 women) indicated that HIV was acquired locally through heterosexual contact. Of the 29 persons, 15 (52%, [four infected and 11 uninfected]) had a history of other STDs, and 28 (97%) reported multiple lifetime sex partners. Three of five infected women had STD co-infection when HIV was diagnosed. Factors associated with HIV infection in the five women were young age (median: 16 years, compared with 25 years for the infected men [KW p=0.05] and 20.5 years for the uninfected women [KW p=0.04]); a stated preference for "much older" sex partners (three of five infected women compared with one of 10 uninfected women [FE p=0.08]); and having had a sex partner who was at least 10 years older (three of four responding infected women compared with two of 10 uninfected women [FE p=0.09]). Infected persons also began engaging in sex at a younger age (median: 13 years; range: 11--14 years compared with uninfected persons, median: 14.5 years, range: 12--17 years; [KW p=0.08]). Alcohol use, drug use, and exchange of sex for alcohol, drugs, or money were not associated with HIV infection in this cluster. Interviews with seven uninfected female social contacts indicated they were similar to the infected women in age (median: 18 years for the social contacts). Common characteristics of infected women and social contacts included low socioeconomic status (seven of 12 women received federal aid), absentee fathers (nine of 12 persons), truancy (six of nine persons in school), and school failure (six of 12 persons having repeated at least 1 year in school). No social contacts reported having had sex partners that were >10 years older than themselves compared with three of the four infected women who responded. Laboratory results and medical histories indicated that antiretroviral therapy was recommended in all infected persons (2). Two persons had seen a doctor since HIV infection was diagnosed. Five of seven persons did not know treatment for HIV infection existed. Of five persons who remembered being referred to care on diagnosis, all were referred to a facility >2 hours away, and one had been seen at that facility. The six remaining persons were willing to be linked to care once they knew HIV care was avail able locally. Survey responses were received from five of six internists and two of six family practitioners. Of the seven responding physicians, one cared for approximately 60 HIV-infected persons and was the only one who reported practices consistent with guidelines for monitoring and treating asymptomatic persons. The others had provided ongoing care to <10 HIV-infected persons; most reported referring persons for care because they lacked experience in HIV treatment. Reported by: State health officers, state epidemiologist, district health officers, and disease intervention specialists, Mississippi State Dept of Health. Div of Applied Public Health Training, Epidemiology Program Office; Div of HIV/AIDS Prevention--Intervention Research and Support, and Div of HIV/AIDS--Surveillance and Epidemiology, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention; and EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report suggest that STDs and multiple sex partners in small town sex networks provide a setting for the transmission of HIV among adolescents in the rural South. HIV infection can spread rapidly through sex networks in low-prevalence rural areas (3). Among adolescents, disadvantaged black women in the South have some of the highest HIV infection rates in the United States and must be a high priority for prevention activities (4). The method by which persons in this cluster were identified underscores the importance of providing routine voluntary HIV counseling and testing services during STD evaluations. In addition, partner counseling and referral services can be especially useful for identifying partners in need of prevention services and for identifying the extent of the HIV-infection network. This cluster also highlights the challenges of service delivery in a rural area with limited HIV prevention and treatment resources. The age-discrepant relations in this cluster have implications for both HIV transmission and primary prevention programs. Adult partners contribute substantially to STDs and pregnancies among teenagers (5). Young women are at risk for HIV infection at an earlier age than are heterosexual men, probably because the women are infected by older sex partners (6). Age difference also may affect adolescents' abilities to negotiate safer sex and condom use. Prevention efforts should address age-discrepant relationships. Secondary prevention measures, such as links to ongoing HIV care and antiretroviral therapy, can improve health and survival and potentially decrease, although not eliminate, infectivity. Following this investigation, efforts to link HIV-infected persons to care have been extended in this health district. Challenges to secondary prevention in rural areas include awareness of treatment options and identification and training of appropriate local HIV care providers. In this cluster, identification of a qualified local care provider facilitated linkage to care and provided a potential point of coordination for social work, mental health care, and case-management services by the local health department. Where no experienced HIV care provider exists, identifying a practitioner willing to accept this role and to develop an ongoing relationship with a remote consultant would be an alternative. References

Figure 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 9/28/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|