|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

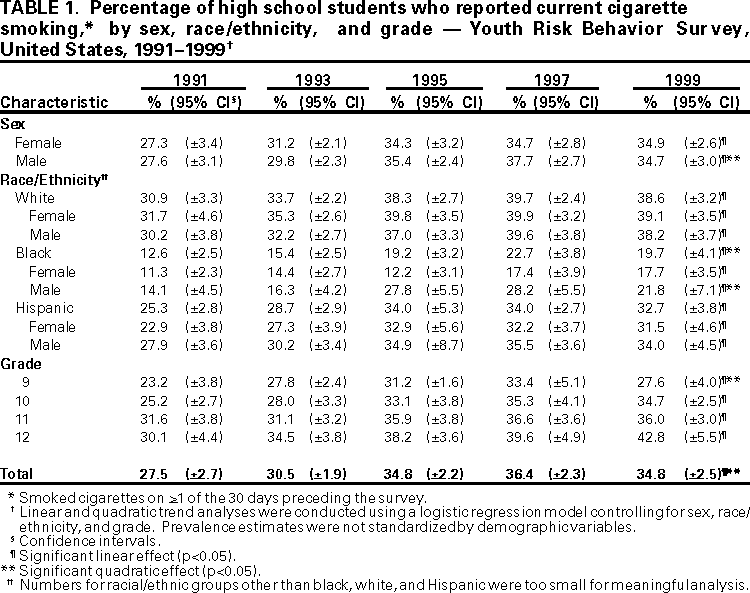

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Trends in Cigarette Smoking Among High School Students --- United States, 1991--1999One of the 10 Leading Health Indicators that reflect the major health concerns in the United States is cigarette smoking among adolescents (1). To examine changes in cigarette smoking among high school students in the United States from 1991 to 1999, CDC analyzed data from the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). This report summarizes the results of the analysis and indicates that current smoking among U.S. high school students increased significantly from 27.5% in 1991 to 34.8% in 1999; however, the analysis also suggested that, later in the decade, current smoking may have leveled or possibly begun to decline. YRBS measures the prevalence of health risk behaviors among adolescents through representative biennial national, state, and local surveys. The 1991, 1993, 1995, 1997, and 1999 national surveys used independent, three-stage cluster samples to obtain cross-sectional data representative of students in grades 9 through 12 in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. In 1991, 1993, 1995, 1997, and 1999, the respective sample sizes were 12,272, 16,296, 10,904, 16,262, and 15,349; school response rates were 75%, 78%, 70%, 79%, and 77%; student response rates were 90%, 90%, 86%, 87%, and 86%; and overall response rates were 68%, 70%, 60%, 69%, and 66%. For each cross-sectional survey, students completed an anonymous, self-administered questionnaire that included identically worded questions about cigarette smoking. Lifetime smoking was defined as having ever smoked cigarettes, even one or two puffs. Current smoking was defined as smoking on >1 of the 30 days preceding the survey. Frequent smoking was defined as smoking on >20 of the 30 days preceding the survey. Data are presented only for non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and Hispanic students because the numbers of students from other racial/ethnic groups were too small for meaningful analysis. Data were weighted to provide national estimates. SUDAAN was used for all data analysis. Secular trends were analyzed using logistic regression analyses that controlled for sex, race/ethnicity, and grade and that simultaneously assessed linear and quadratic time effects. Quadratic trends suggest a significant but nonlinear trend in the data over time. When a significant quadratic trend accompanies a significant linear trend, the data demonstrate some nonlinear variation (e.g., leveling or change in direction) in addition to a linear trend. The prevalence of lifetime smoking remained stable from 1991 to 1999 among high school students overall and among all sex, racial/ethnic, and grade subgroups except 10th-grade students. In 1999, 70.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]=±3.0) of all students reported lifetime smoking. Among 10th-grade students, lifetime smoking showed a significant linear trend from 1991 (68.3% [95% CI=±3.3]) to 1999 (73.9% [95% CI=±4.1]). From 1991 to 1999, current smoking exhibited a significant linear trend among students overall and among all sex, racial/ethnic, and grade subgroups (Table 1). The overall prevalence of current smoking was 27.5% in 1991 and 34.8% in 1999. A simultaneous quadratic trend was identified for students overall, suggesting a leveling or possible decline in current smoking. The male, black, black male, and 9th-grade student subgroups also showed this simultaneous quadratic trend. Each year, white students were significantly more likely than Hispanic students, who were significantly more likely than black students, to report current smoking (except in 1995 when white and Hispanic students were equally likely to report current smoking, but both were significantly more likely than black students to report this behavior). In 1991, white students were 2.5 times more likely than black students and 1.2 times more likely than Hispanic students to report current smoking. In 1999, white students were 2.0 times more likely than black students and 1.2 times more likely than Hispanic students to report current smoking. The prevalence of frequent smoking showed a significant linear trend from 1991 to 1999 among students overall and in all sex, racial/ethnic, and grade subgroups, except for Hispanic female students. The overall prevalence of frequent smoking was 12.7% (95% CI=±2.2) in 1991 and 16.8% (95% CI=±2.5) in 1999. Among Hispanic female students, the prevalence of frequent smoking remained stable from 1991 to 1999. For each of the five surveys, white students were significantly more likely than black and Hispanic students to report this behavior. Reported by: Office on Smoking and Health, and Div of Adolescent and School Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Editorial Note:Despite a leveling or possible decline in current smoking among youth overall during the late 1990s, this trend may have been limited to selected groups (i.e., male, black, black male, and 9th-grade students). In addition, frequent smoking rates overall and in all sex, racial/ethnic, and grade subgroups (except Hispanic females) were significantly higher in 1999 than in 1991 and showed no pattern of leveling or declining. Additional research is needed to understand how current smoking rates and secular changes in these rates vary among racial/ethnic groups. For example, throughout the decade, YRBS and other national surveys found that black high school students smoked at lower rates than white and Hispanic high school students (2,3); however, the 1999 National Youth Tobacco Survey (2) reported that current smoking rates among black middle school students were similar to rates among white and Hispanic middle school students. Among grade subgroups, data for 9th-grade students suggested a leveling or possible decline in current smoking. Current smoking among 12th-grade students continued to rise each year. A previous study suggested that current smoking peaked among 10th and 12th-grade students in 1996 and 1997, respectively (3). It is unclear whether future YRBS data will show a delayed peak among 10th and 12th-grade students. The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, these data apply only to adolescents who attend high school. In 1998, 5% of persons aged 16--17 years were not enrolled in a high school program and had not completed high school (4). Second, the extent of underreporting or overreporting in YRBS cannot be determined, although the survey questions demonstrate good test-retest reliability (5). Finally, using only five data points makes it possible to characterize trends over the decade but difficult to accurately characterize the direction current smoking will take during the next decade. Reducing the prevalence of current smoking among adolescents to 16% is one of the goals of the Leading Health Indicators. Achieving this goal by 2010 will require a 54% reduction in current smoking among adolescents nationwide. Data from Florida, where comprehensive tobacco-control programs have been initiated, suggest such declines are possible. From 1998 to 2000 in Florida, current smoking declined 40% among middle school students and 18% among high school students (6). CDC recommends that communities fully implement its "Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs" by establishing comprehensive, sustainable, and accountable tobacco-control programs (7). In addition, communities should follow CDC's "Guidelines for School Health Programs to Prevent Tobacco Use and Addiction," which recommend implementing school-based tobacco-use prevention programs in grades K--12 with intensive instruction in grades 6--8 and supporting cessation efforts for nicotine-dependant students (8,9). Finally, comprehensive tobacco-control programs also should reduce the appeal of tobacco products, implement mass media campaigns, increase tobacco excise taxes, implement policy and regulation of tobacco products, and reduce youth access to tobacco products (10). References

Table 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 8/24/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|