|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

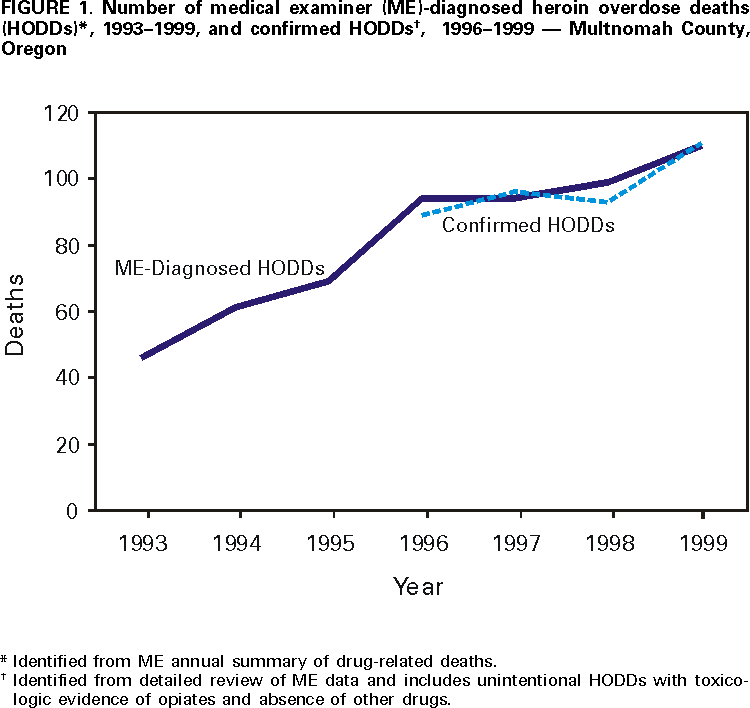

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Heroin Overdose Deaths --- Multnomah County, Oregon, 1993--1999In the United States, heroin use is increasing and was implicated in 3805 deaths in 1993 (1). Multnomah County is Oregon's most populous county (1998 estimated population: 641,900); three fourths of county residents live in Portland. In 1999, in response to community concerns, the Multnomah County Health Department analyzed medical examiner (ME) data for 1993--1999 and interviewed heroin users to characterize heroin overdose deaths (HODDs) in the county. This report summarizes the findings of these studies, which indicate that HODDs in the county more than doubled from 1993 to 1999 (from 46 to 111), and that interviews with users helped identify possible public health interventions. For 1993--1999, ME-diagnosed HODDs were identified using the ME annual summary of drug-related deaths. For 1996--1999, the Multnomah County Health Department conducted a detailed review of ME records of drug-related deaths, which included those resulting from overdose and other drug-related causes (e.g., injury and disease deaths in which drugs played a role). ME-diagnosed HODDs for 1996--1999 were within 6.5% of those identified in the detailed case review. During 1993--1999, 573 ME-diagnosed HODDs were identified. During 1996--1999, 517 drug-related deaths occurred in Multnomah County; 85 attributed to causes other than unintentional overdose (e.g., homicide and suicide) were excluded. Of the remaining 432 deaths, 389 (90.0%) were classified as unintentional HODDs based on laboratory evidence of opiates in blood or other specimens and absence of historic, scene, or toxicologic evidence of poisoning with other drugs, including other opiates. Of the 389 HODDs, 337 (86.6%) were in Multnomah County residents. HODDs more than doubled from 1993 (n=46) to 1999 (n=111) (Figure 1). In 1999, the cause-specific death rate from HODDs among all county residents was 15.1 per 100,000 population. Of the 389 HODDs, 333 (85.6%) were in males. Almost half (46.8%) were in persons aged 45--54 years; 23.1%, aged 35--44 years; 22.9%, aged 25--34 years; and 4.9%, aged <25 years. The median ages for males (40.0 years) and females (37.5 years) were similar. The race/ethnicity of persons who died of heroin overdose reflected the county population. Approximately half (47.6%) of HODDs occurred in users' homes, 13.4% occurred in friends' homes, and 13.4% in hotels/motels. Only 18.8% of the HODDs occurred in public settings where a passerby might have found the person who had overdosed. Toxicology results were analyzed for 115 consecutive HODDs during October 1998--December 1999; for 58.3% of these HODDs, alcohol and/or drugs in addition to heroin were detected. The substances most commonly identified along with heroin were cocaine (26.1%), benzodiazepines (15.7%), and alcohol (10.4%). To gather data on circumstances of overdose and identify intervention opportunities, investigators interviewed heroin users with a history of overdose. Ten current users were recruited through posters in hotels and referrals from needle-exchange programs. Eight former users early in recovery (i.e., abstinent from heroin for <14 weeks) were recruited through a drug-free housing program. Respondents were asked about 1) drug availability, sources, cost, and potency; 2) drug use patterns; 3) personal experience with heroin overdose; and 4) response to companion's overdose. Respondents reported that "black tar" heroin from Mexico or South America was the primary type used in the community and that heroin and other drugs are readily available and inexpensive. Users reported great variability in the potency of heroin sold in Multnomah County. Users also reported that injection was the primary route of administration. Regular heroin users develop tolerance to higher doses. When heroin use is interrupted, heroin doses that were previously well-tolerated can cause overdose. Heroin users described several situations in which heroin use was interrupted: involuntarily, when incarcerated or lacking money to purchase heroin, and voluntarily, during attempts to stop using heroin. Regardless of the reason for the interruption, users reported they tended to resume injecting heroin at their usual dose and sometimes overdosed. Users believed that risk for overdose was greater when they used alcohol and other drugs with heroin, injected heroin without companions, and had another person inject drugs for them. Heroin users' responses to a companion's overdose reflected a strong desire to avoid contact with law enforcement and medical systems. Three fourths of respondents reported that they hesitated to call for emergency assistance for fear of being arrested. Many attempted to resuscitate overdosed companions on their own. Users also described leaving overdose victims in public places, hoping that they would be discovered and helped by others. Reported by: GL Oxman, MD, Multnomah County Health Dept; S Kowalski, PhD, L Drapela, PhD/ABD, Evaluation and Research Unit, Multnomah County Dept of Support Svcs; ES Gray, N Hartshorne, MD, Oregon State Medical Examiner Program; S Fafara, H Lyons, E Blackburn, Recovery Association Project, Portland, Oregon. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate that HODDs are a major and increasing public health problem in Multnomah County. In 1999, it was a leading cause of death among men aged 25--54 years, with a cause-specific death rate of 47.8 per 100,000 population. The ethnographic interviews provide some data about the circumstances and risk factors for heroin overdose in Multnomah County. Variations in heroin potency (2,3), intermittent and interrupted heroin use (4), use of other drugs and alcohol (5), and variable heroin tolerance (6) can increase the risk for overdose and death. Failure to use emergency medical services has been associated with fatal heroin overdose (7). The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, surveillance for HODD is difficult because ME classification of overdose deaths is inconsistent (8). Second, this study probably underestimated the impact of heroin overdose on the county. Thirty-two HODDs were excluded from the analysis because they were not clearly unintentional overdoses, and 52 were excluded from death rate calculations because they did not occur in county residents. Third, the difficulty in reconstructing the social and behavioral context of overdose deaths complicates both surveillance of HODDs and identification of prevention opportunities. Finally, ethnographic data may not be representative of injecting-drug users in Multnomah County because those interviewed were from a convenience sample. Several approaches may help to prevent HODDs. Improved public health surveillance should enable identification of risks and protective factors and help monitor the impact of interventions. Heroin use can be reduced by primary prevention of the initiation of drug use and substance abuse treatment (particularly methadone maintenance) for active users. Other steps can be considered to reduce HODDs among users who cannot or will not stop injecting. Improving use and quality of emergency medical response and treatment can improve outcomes. Working with police to establish policies that persons reporting or suffering drug overdose are not subject to arrest could increase users' willingness to seek emergency assistance (9). Users can be counseled about the risks for heroin overdose and how to avoid them (1,9,10). Some programs train injecting-drug users and their partners in the use of naloxone, an opiate antagonist highly effective in reversing the effects of opiate overdose but that can induce withdrawal and requires medical supervision (1,9). Implementing interventions to decrease heroin and other fatal drug overdoses will require partnerships among a range of groups and programs, including public health, substance abuse treatment, syringe exchange/community outreach programs, emergency medical services, and police and criminal justice departments. Planning and implementation should involve heroin users because their knowledge, skills, and social networks can help identify interventions and achieve acceptance of interventions among the drug users at risk for drug overdose. References

Figure 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: 7/20/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|