At a glance

The domestic medical screening guidance is for state public health departments and healthcare providers in the United States who conduct the initial medical screening for refugees. These screenings usually occur 30-90 days after the refugees arrive in the United States. This guidance aims to promote and improve refugee health, prevent disease, and familiarize refugees with the U.S. healthcare system.

Overview

This guidance briefly describes the required overseas tuberculosis (TB) medical screening process for refugees resettling in the United States and outlines the recommended evaluation of newly arrived refugees for TB during the domestic medical screening examination. This document supplements CDC guidelines for the general U.S. population and highlights specific needs among refugees to be used in conjunction with guidance from state TB control programs.

- All refugee applicants must undergo evaluation overseas for TB and are assigned one or more TB classifications prior to departure. Overseas TB screening results, treatment, and classifications are documented on the US Department of State (DS) forms.

- As part of the domestic screening, all overseas medical records should be reviewed, a thorough medical history obtained, and a physical examination completed.

Background

The United States has one of the lowest TB rates in the world and most U.S. residents are at minimal risk for TB1. However, the epidemiology of TB reflects persistent disparities by origin (country) of birth and race and ethnicity in the United States1. Origin of birth is a prominent risk factor for TB in the United States because of the substantially greater risk of exposure to TB outside the United States2. In 2023, 76% of cases in the United States occurred among non-U.S.-born persons1.

Studies have indicated that reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI), rather than recent transmission, is the primary driver of TB disease in the United States, accounting for approximately 85% of all TB cases12. Therefore, it is important that clinicians identify and offer treatment for LTBI soon after arrival to prevent development of TB disease in refugees, and evaluation has shown that the domestic medical screening examination can be a highly effective method to identify LTBI3. The risk for development of TB disease appears to remain high for many years after resettlement, so clinicians who serve refugees, immigrants, and other newcomers should maintain a high index of suspicion for TB diseases even long after arrival4. Living conditions and other factors may place refugees at continued risk of exposure to TB. The prevalence of drug-resistant TB and extrapulmonary TB are also higher among non-U.S.-born persons2. Clinicians should consider these conditions when caring for new arrivals.

Overview of Overseas Tuberculosis Screening for Refugees

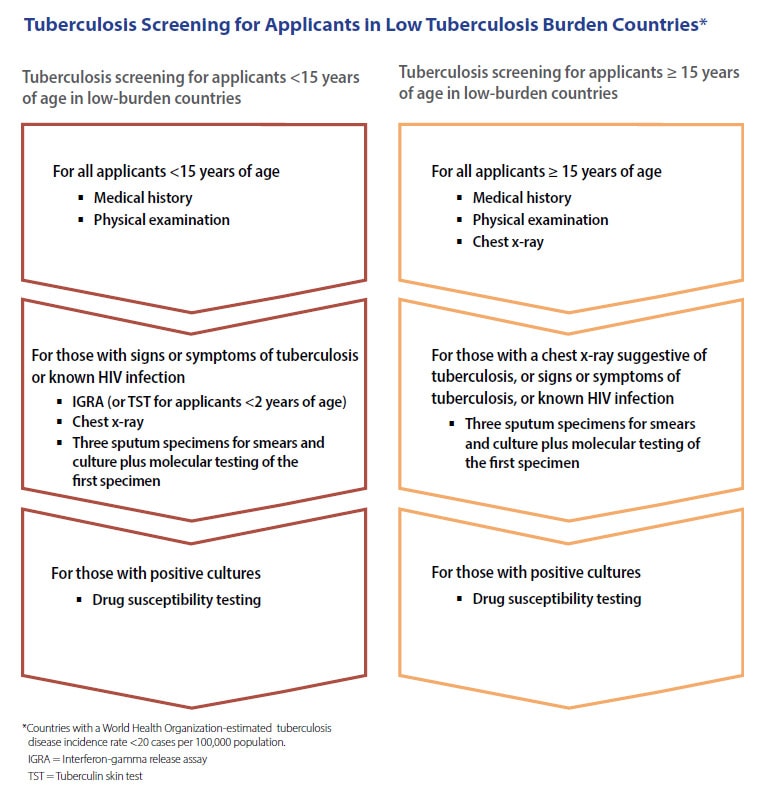

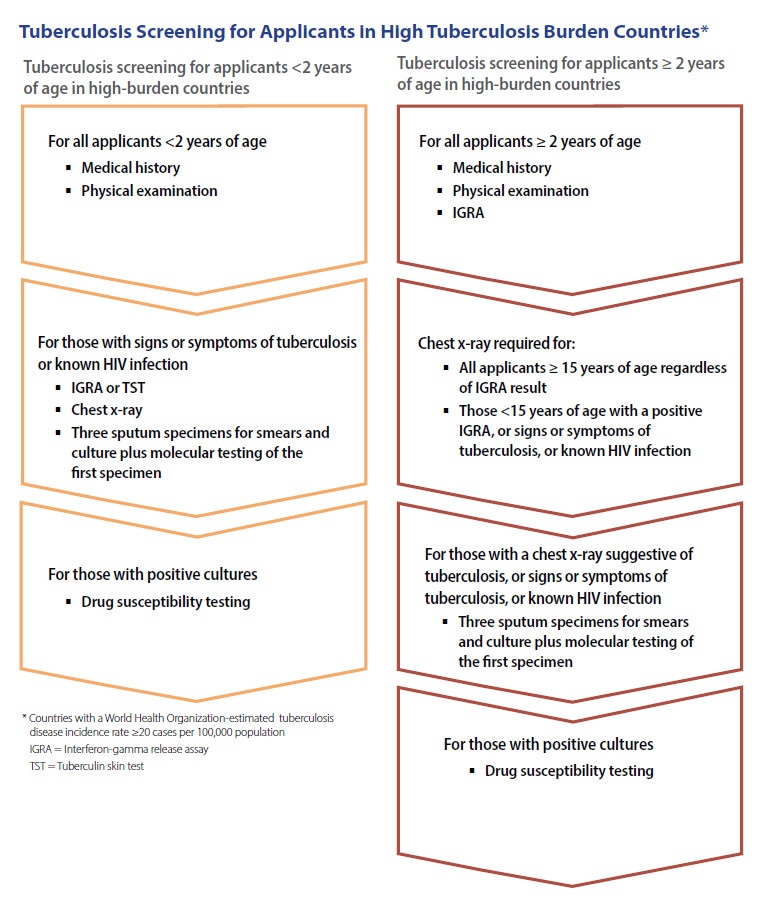

Before departure for the United States, all refugees must undergo an overseas medical examination that focuses on inadmissible conditions, including infectious TB disease. By law, refugees diagnosed with an inadmissible condition are not permitted to depart for the United States until the condition has been treated, unless they obtain a waiver from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services within the Department of Homeland Security. CDC stipulates the content of the overseas medical examination through Technical Instructions (TIs) issued to panel physicians and organizations that perform the medical screening examinations. Figure 1 outlines the required TB screening components for refugees being resettled to the United States from countries with a low or high burden of TB. For the purposes of screening, low burden is defined as any country with World Health Organization (WHO)-estimated TB disease incidence rate of < 20 cases per 100,000 population and high burden as any country with a WHO-estimated TB disease incidence rate of ≥ 20 cases per 100,000 population.

Figure 1. Overseas tuberculosis (TB) screening for applicants in low and high TB burden countries

Source: CDC Division of Global Migration Health, Tuberculosis Technical Instructions for Panel Physicians

Classifications and Travel Clearance

All refugee applicants must be assigned one or more TB classifications. TB classification is determined by screening results, and treatment, if required (see TB TI for panel physicians for the TB classifications and travel clearance for all refugee applicants).

Documentation of Overseas TB Evaluation

Panel physicians must document TB screening and treatment results on the DS 2054 (Medical Examination), DS 3030 (TB Worksheet), and DS 3026 (Medical History and Physical Examination Worksheet) forms. All medical documentation must be included with the required DS forms. Refugees receive copies of these documents and should provide them to the evaluating provider in the United States. In addition, the information is available through CDC's Electronic Disease Notification (EDN) system to state or local health departments at refugees' U.S. destinations. Evaluating providers in the United States who are not receiving this information should contact the state refugee coordinator or state refugee health program. Overseas medical documents include information pertinent to the TB evaluation, such as:

- Screening information

- Medical history and physical examination

- The interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) laboratory report or TB skin test (TST) documentation (including name of product, expiration date, amount administered), if either of these tests was conducted

- Radiology report of digital chest X-ray (CXR) findings for all applicants aged ≥15 years, and for younger applicants when conducted

- DICOM chest X-ray image, if CXR conducted

- Medical history and physical examination

- Diagnostic information

- Sputum acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear, molecular testing, and culture results for TB, if such testing was conducted

- Drug susceptibility test results for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolate

- Sputum acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear, molecular testing, and culture results for TB, if such testing was conducted

- Overseas treatment information for applicants with infectious TB disease

- Direct observed therapy regimen received, including does of all medications, start and completion dates, and periods of interruption

- Radiology reports of CXR findings before, during and at the end of treatment

- Sputum AFB smear reports obtained before, during, and at the end of treatment

- Reports of culture findings obtained before, during, and at the end of treatment, including reports of contamination

- Reports on clinical course, such as clinical improvement or lack of improvement, during and after treatment

- Direct observed therapy regimen received, including does of all medications, start and completion dates, and periods of interruption

Treatment for LTBI is not required as part of the overseas medical examination but may be offered by the panel physician on a voluntary basis if the panel physician is able to do so. CDC encourages applicants diagnosed with LTBI overseas to seek treatment. Panel physicians are instructed that they may offer voluntary LTBI therapy to contacts of tuberculosis cases, who are diagnosed with LTBI, if the panel physician is able to do so. In addition, directly observed preventive therapy is recommended overseas for applicants <4 years old or with impaired immunity (e.g., HIV infection) who are contacts of a person with known infectious TB disease and who have a negative evaluation for TB disease, regardless of IGRA results. If overseas treatment is provided, it should be documented on the DS forms and available in EDN. For more information, see the Technical Instructions.

Domestic Refugee Screening for Tuberculosis

All refugees should receive a comprehensive domestic medical screening within 90 days of arrival. The goal of the domestic screening for TB is to find persons with LTBI, and to find persons who may have developed TB disease since the overseas medical examination, to facilitate prompt treatment and prevent transmission.

Medical History and Physical Examination of Refugees for Tuberculosis during the Domestic Medical Screening Evaluation

TB disease should be encountered infrequently during the domestic medical screening examination because all new refugee arrivals have been screened for TB disease prior to departure. Clinicians should be aware that the overseas medical exam is aimed at diagnosing infectious TB disease and may fail to detect all forms of extrapulmonary disease. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to perform a thorough history and physical examination aimed at identifying any refugee who may have pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB disease. Some persons with TB disease have minimal symptoms, and a high index of suspicion should be maintained for those with any concerning history, such as household exposure to TB, or signs of active disease.

All predeparture medical records for the refugee should be closely reviewed. A thorough medical history should be obtained post arrival. In addition to current signs or symptoms of TB disease (e.g., weight loss, night sweats, fever, cough), specific information may be helpful in recognizing persons who might have TB disease or LTBI:

- Previous history of TB

- Prior treatment suggestive of TB treatment

- Prior diagnostic evaluation suggestive of TB

- Family or household contact with a person who has or had TB disease, treatment, or diagnostic evaluation suggestive of TB

In addition, in children, a history of recurrent pneumonias, paroxysmal wheezing, failure to thrive, or recurrent or persistent fevers should increase the index of suspicion.

Signs and symptoms of pulmonary TB are often indolent and nonspecific, and include malaise, weight loss, night sweats, cough, chest pain, fever, and hemoptysis. Symptoms of extrapulmonary TB disease generally reflect the organ involved (e.g., abdominal pain with gastrointestinal TB). Although extrapulmonary TB can be found in nearly any organ of the body, lymph nodes, including those in the thorax, are the most common extrapulmonary sites.

For general guidance on the physical examination, see History and Physical Examination Screening Guidance. The examination for TB should include inspection and palpation of all major palpable lymph node beds and a careful skin examination, as it may reveal cutaneous disease, erythema nodosum, scars from scrofula, or hints of prior chest surgery.

Testing Newly Arrived Refugees for TB Infection and Disease

Domestic TB testing recommendations are based on signs and symptoms of TB and the results of screenings refugees received overseas.

- Any new arrival with signs or symptoms of TB, regardless of country of origin, should undergo clinical evaluation for TB disease.

- For refugees aged <2 years with no clinical evidence of TB disease, and who have not previously received treatment for TB disease or LTBI:

- If no IGRA (or TST) was completed overseas (or result was indeterminate*), and there are no signs or symptoms of TB disease upon physical examination, conduct TST. Skin testing and interpretation should be completed in accordance with the ATS/CDC/IDSA Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children.

- If IGRA (or TST) was negative overseas (within the last 6 months), and there are no signs or symptoms of TB disease upon physical examination, no further domestic evaluation is needed.

- If the overseas IGRA (or TST) was negative but performed ≥6 months prior to the domestic examination, and there are no signs or symptoms of TB, conduct TST.

- Treatment for LTBI should be offered after TB disease is ruled out for those with positive IGRA (or TST) results (if there are no contraindications).

- If no IGRA (or TST) was completed overseas (or result was indeterminate*), and there are no signs or symptoms of TB disease upon physical examination, conduct TST. Skin testing and interpretation should be completed in accordance with the ATS/CDC/IDSA Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children.

- For refugees aged ≥2 years with no clinical evidence of TB disease, and who have not previously received treatment for TB disease or LTBI:

- If no IGRA (or TST) was completed overseas (or the IGRA result was indeterminate*), and there are no signs or symptoms of TB disease upon physical examination, conduct IGRA.

- If IGRA (or TST) was negative overseas (within the last 6 months), and there are no signs or symptoms of TB disease upon physical examination, no further domestic evaluation is needed.

- If the overseas IGRA (or TST) was negative but performed ≥6 months prior to the domestic examination, repeat IGRA (or TST).

- Treatment for LTBI should be offered after TB disease is ruled out for those with positive IGRA (or TST) results (if there are no contraindications).

- If no IGRA (or TST) was completed overseas (or the IGRA result was indeterminate*), and there are no signs or symptoms of TB disease upon physical examination, conduct IGRA.

*The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two TB blood tests that are commercially available in the United States: QuantiFERON®-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) and T-SPOT®.TB test (T-Spot). While QFT-Plus can provide a positive, negative, or indeterminate result, the T-spot test can provide a positive, negative, invalid, or borderline result. For this guidance, invalid or borderline results may be interpreted as indeterminate.

Additional Testing Considerations

- Refugees may be assigned Class B3 TB (i.e., a recent contact of a person with known infectious TB disease) regardless of overseas IGRA or TST results. Applicants can be both Class B3 and Class B1 (a contact who required sputum testing with negative cultures), or Class B3 and Class B2 (a contact with LTBI):

- If overseas evaluation occurred <8 weeks after contact ended and the IGRA (or TST) was negative or indeterminate, refugees assigned Class B3 TB should be evaluated domestically with IGRA (or TST) at least 8 - 10 weeks after contact ended.

- If overseas evaluation occurred <8 weeks after contact ended and the IGRA (or TST) was negative or indeterminate, refugees assigned Class B3 TB should be evaluated domestically with IGRA (or TST) at least 8 - 10 weeks after contact ended.

- Living conditions and other factors may place refugees at continued risk of exposure to TB after the overseas examination while still overseas or after arrival in the U.S. During the history and physical exam, clinicans should consider inquiring about risk factors for continued exposure and repeating LTBI screening if negative or indeterminate overseas, if necessary.

Testing for Infection

TB Blood Tests (Interferon Gamma Release Assay [IGRA])

An IGRA is a blood test used to determine if a person is infected with M. tuberculosis. IGRAs measure a component of cell-mediated immunity reactivity to M. tuberculosis in fresh whole blood. Food and Drug administration-approved IGRA tests are recommended for TB testing in the United States. It is important to note that IGRA should not be performed on a person who has written documentation of either a previous positive TB test result (IGRA or TST) or treatment for TB disease. For additional information on TB blood tests, refer to the Clinical Testing Guidance for Tuberculosis: Interferon Gamma Release Assay.

Mantoux Tuberculin Skin Test (TST)

The TST is performed by injecting a small amount of a standardized fluid (called tuberculin PPD solution) under the skin, usually on the volar surface of the forearm. A person given the tuberculin skin test must return within 48 to 72 hours to have a trained health care provider look for a reaction on the arm. In otherwise healthy refugees from areas of the world where TB is common, ≥10 mm of induration is considered a positive result. A cutoff of ≥5 mm of induration is considered a positive result in persons with HIV infection, those with recent close contact with a known case of infectious TB, persons with fibrotic changes on CXR consistent with prior TB, persons with organ transplants, and other immunosuppressed persons (see CDC’s Clinical Testing Guidance for Tuberculosis: Tuberculin Skin Test). Many refugees from TB-endemic areas have been vaccinated against TB with BCG vaccine. IGRA is preferred for testing persons who have been vaccinated with BCG. Although previous BCG vaccination may influence TST results, especially in infants, a history of vaccination with BCG should not influence interpretation of TST results in adults. Some refugees may believe their test is positive due to past BCG vaccination, but clinicians should be prepared to thoroughly explain the reasons for not considering BCG vaccination in the interpretation of TST or IGRA results (for more information, see CDC’s Tuberculosis Vaccine webpage). For additional information about performing a TST, visit the CDC Mantoux Tuberculin Skin Test Toolkit.

A summary of recommended uses, benefits, and limitations for IGRA and TST can be found in the ATS/CDC/IDSA Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. It should be noted that a negative IGRA or TST result does not exclude TB disease from the differential diagnosis in a person with signs or symptoms of TB disease. Additionally, a positive test result, from either IGRA or TST, should be accompanied by an evaluation for TB disease with a thorough history and examination for signs and symptoms and a CXR.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Chest Radiography (CXR)

Any patient with signs or symptoms of TB disease should have a CXR. If CXRs from the overseas medical exam are available and there has been no change in clinical status (no new signs or symptoms of pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB disease or new positive TB infection test), there is no need to repeat the CXR. However, clinical judgment should be used in each case. If documentation is not available at the initial screening visit, providers should contact their State Refugee Coordinator, or the CDC (MHINx@cdc.gov) to obtain overseas testing results. If overseas CXR results cannot be obtained, or the test was done >6 months prior and the result was negative, repeat CXR should be considered.

Confirmed LTBI

Some states require LTBI reporting. Asymptomatic refugees with positive IGRA or TST results and normal findings on CXR should be offered LTBI treatment in accordance with CDC guidelines5. Information on how to choose the most effective treatment regimen for each patient, adverse drug effects, monitoring, and assessing adherence is available on the CDC’s Treatment Regimens for LTBI webpage.

Suspected or Confirmed TB Disease

Screening results indicating TB disease may include a combination of positive results from IGRA or TST, abnormal findings on CXR, pathology findings consistent with TB disease (e.g., caseating granuloma), signs or symptoms consistent with TB disease, sputum or tissue smear positive for AFB, a positive nucleic acid amplification test, or a culture positive for M. tuberculosis complex. Prompt treatment should be initiated for presumptive or confirmed clinical TB disease. All presumptive or confirmed cases (pulmonary or extrapulmonary) should be reported to the local health authorities within 24 hours of determination so that appropriate public health measures can be implemented and management with an infectious disease or TB expert can be implemented. Culture confirmation is not needed before starting therapy for cases with a high index of suspicion. When pulmonary or laryngeal TB is suspected, the person should be isolated in an appropriate setting to prevent spread of infection until the patient is no longer considered infectious.

Tuberculosis Treatment

A complete discussion of treatment for TB disease and LTBI is beyond this scope of this guidance document; however, more information on treatment can be found at: Treatment for TB disease webpage and Treatment Regimens for Latent TB Infection webpage. The CDC recommends use of directly observed therapy (DOT) during TB treatment, and video DOT (vDOT) is recommended as an equivalent alternative to in-person DOT for patients on treatment for TB (see CDC Video Directly Observed Therapy During Tuberculosis Treatment).

Domestic Tuberculosis Screening for New Arrivals Other than Refugees

The introduction of alternative pathways to enter the United States has allowed parolees, asylees, and some migrants eligibility for financial assistance to cover the cost of the domestic medical exam. However, providers should be aware that the overseas medical screening provided to individuals in these groups may differ from the screening provided to refugees. Providers should review the past medical history for these individuals to fully understand the TB screening and treatment that was provided overseas. While this domestic TB guidance was written primarily to address the evaluation of refugees, it can also be used as a reference tool for completing the physical examination and TB screening for other new arrivals.

Additional Information

Additional information regarding tuberculosis can be found on the CDC’s Clinical Overview of Tuberculosis webpage.

- Williams P.M., et. al., Tuberculosis – United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73:265-270.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2021. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2022.

- Nuzzo, J.B., et. al., Postarrival Tuberculosis Screening of High-Risk Immigrants at a Local Health Department, American Journal of Public Health 105, no. 7 (July 1, 2015): pp. 1432-1438.

- Tsang, C.A., et al., Tuberculosis Among Foreign-Born Persons Diagnosed >/=10 Years After Arrival in the United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2017. 66(11): p. 295-298.

- Sterling, T.R., et al., Guidelines for the Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2020. 69(1): p. 1-11.