Key points

- Atrioventricular septal defect (pronounced EY-tree-oh-ven-TRIC-u-lar SEP-tal DEE-fekt) or AVSD is a congenital heart defect. Congenital means present at birth.

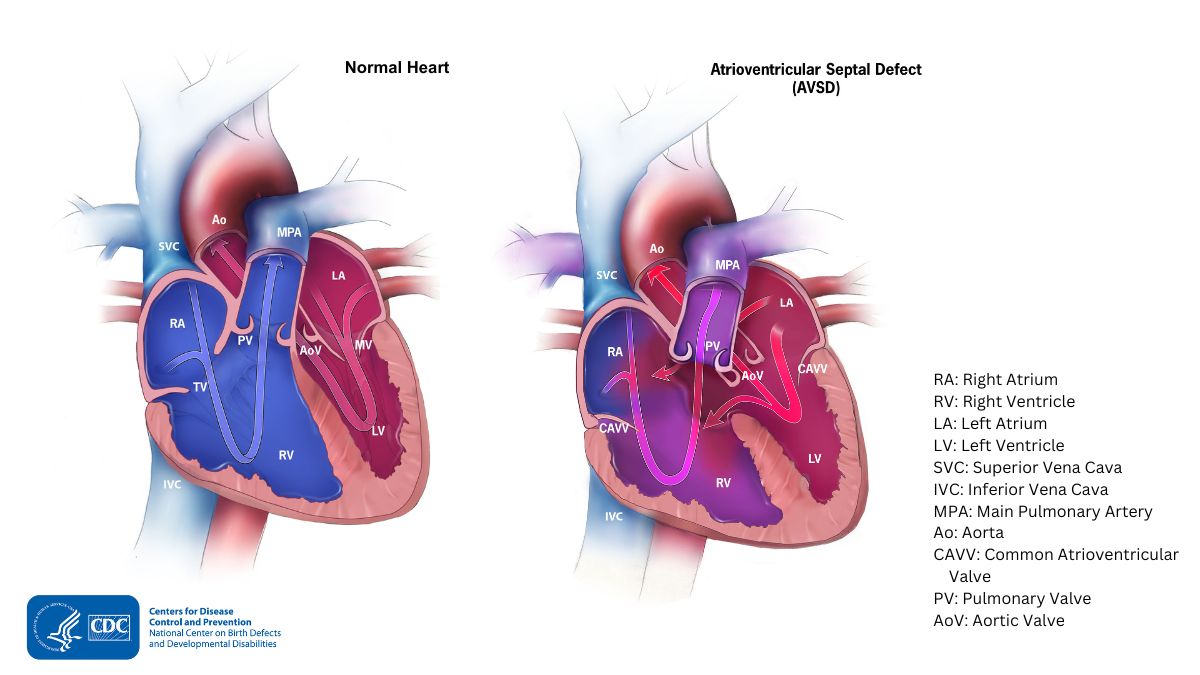

- An AVSD affects the valves and walls between the heart's upper and lower chambers.

- Surgical repairs for AVSD are not a cure.

- People with AVSD should have routine checkups with a heart doctor to stay as healthy as possible.

What it is

An AVSD occurs when there are holes between the chambers of the right and left sides of the heart. This condition is also called atrioventricular canal (AV canal) defect or endocardial cushion defect. In people with AVSD, the valves that control blood flow between these chambers may not form correctly.

In AVSD, blood flows where it normally should not go. The blood may also have a lower-than-normal amount of oxygen, and extra blood can flow to the lungs. This extra blood being pumped into the lungs forces the heart and lungs to work harder than usual. This may lead to heart failure.

Occurrence

About 1 in 1,712 (about 2,154) babies in the United States are born with an AVSD each year.[1]

Types

There are two general types of AVSD that can occur. The types depend on which structures are not formed correctly.

Complete AVSD

A complete AVSD occurs when there is a large hole in the center of the heart. This allows blood to flow between all four chambers of the heart. This hole occurs where the septa (walls) separating the two top chambers (atria) and two bottom chambers (ventricles) normally meet. There is also one common valve in the center of the heart instead of two separate valves. This common valve often has leaflets (flaps) that may not be formed correctly or do not close tightly. A complete AVSD arises during pregnancy when:

- The common valve fails to separate into the two distinct valves, the tricuspid valve on the right side of the heart and the mitral valve on the left side, and

- The walls that split the upper and lower chambers of the heart do not grow all they way to meet in the center of the heart.

Partial or incomplete AVSD

A partial or incomplete AVSD occurs when the heart has some, but not all of the defects of a complete AVSD. There is usually a hole in the atrial wall or in the ventricular wall near the center of the heart. A partial AVSD usually has both mitral and tricuspid valves, but one of the valves (usually mitral) may not close completely. This allows blood to leak backward from the left ventricle into the left atrium.

Signs and symptoms

Babies with a complete AVSD usually have symptoms within the first few weeks after birth. When symptoms occur, they may include:

- Breathing problems

- Weak pulse

- Ashen or bluish skin color

- Poor feeding, slow weight gain

- Tiring easily

- Swelling of the legs or belly

Certain symptoms may indicate that a baby's complete AVSD or partial AVSD is getting worse. These symptoms include:

- Arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm). An arrhythmia can cause the heart to beat too fast, too slow, or irregularly. When the heart does not beat properly, it can't pump blood effectively.

- Heart failure. When the heart cannot pump enough blood and oxygen to meet the needs of the body.

- Pulmonary hypertension, a type of high blood pressure that affects the arteries in the lungs and the right side of the heart.

For partial AVSDs, the holes between the chambers of the heart may not be large. Therefore, signs and symptoms may not occur in the newborn or infancy periods. In these cases, people with a partial AVSD might not be diagnosed for years.

Complications

Infants who have surgical repairs for AVSD are not cured and may have lifelong complications. The most common complication is a leaky mitral valve. This is when the mitral valve does not close fully, allowing blood to flow backwards through the valve. A leaky mitral valve can cause the heart to work harder to get enough blood to the rest of the body. A leaky mitral valve might have to be surgically repaired.

Risk factors

The causes of AVSDs among most babies are unknown. Some babies have heart defects because of changes in their genes or chromosomes. A combination of genes and other risk factors may increase the risk for AVSD. These factors can include things in a mother's environment, what she eats or drinks, or the medications she uses during pregnancy.

AVSD is common in babies with Down syndrome

Diagnosis

AVSD may be diagnosed during pregnancy or soon after the baby is born.

During pregnancy

During pregnancy, screening tests (prenatal tests) check for birth defects and other conditions. An ultrasound, a tool that creates pictures of the baby, may detect an AVSD. However, it usually depends on the size or type (partial or complete) of the AVSD.

The healthcare provider can request a fetal echocardiogram to confirm the diagnosis if AVSD is suspected. A fetal echocardiogram is an ultrasound of the unborn baby's heart and shows more detail than the routine prenatal ultrasound test. The fetal echocardiogram can show problems with the structure of the heart and how well the heart is working.

After the baby is born

During a physical exam of an infant, a complete AVSD may be suspected. Using a stethoscope, a doctor may hear a heart murmur (a "whooshing" sound caused by irregular blood flow through the heart). However, not all heart murmurs are present at birth.

A healthcare provider may request additional tests to confirm the diagnosis of AVSD. These tests include:

- Echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart)

- Electrocardiogram (EKG) (measures electrical activity of the heart)

- Chest X-ray

- Other medical tests

Treatments

All AVSD types usually require surgery. During surgery, any holes in the chambers are closed using patches. If the mitral valve does not close completely, it is repaired or replaced. For complete AVSD, the common valve is separated into two valves—one on the right side and one on the left.

The age for surgical repair depends on the child’s health and the specific structure of the AVSD. If possible, surgery should occur before there is permanent damage to the lungs from too much blood pumping to the lungs. Medication may be used to treat heart failure. However, this is only a short-term measure until the infant can grow large enough for surgery.

Even if their AVSD is surgically repaired, a child or adult with an AVSD needs regular visits with a cardiologist to:

- Monitor his or her progress

- Avoid complications

- Check for other health conditions that might develop as the child ages

With proper treatment, most babies with AVSD grow up to lead healthy, productive lives.

- Stallings EB, Isenburg JL, Rutkowski RE et al; for the National Birth Defects Prevention Network. National population-based estimates for major birth defects, 2016–2020. Birth Defects Res. 2024;116(1):https://doi.org/10.1002/bdr2.2301