Key points

- A blood clot that occurs as a result of hospitalization, surgery, or other healthcare treatment or procedure is called healthcare-associated venous thromboembolism (HA-VTE)

- As many as 70% of cases of HA-VTE could be prevented but fewer than half of hospitalized patients receive appropriate prevention measures

- CDC has several activities aiming to reduce the impact of HA-VTE

What Is healthcare-associated venous thromboembolism?

People who are currently or recently hospitalized or recovering from surgery are at increased risk of developing serious and potentially deadly blood clots in the form of venous thromboembolism (VTE). A blood clot that occurs as a result of hospitalization, surgery, or other healthcare treatment or procedure is called healthcare-associated venous thromboembolism (HA-VTE).

Who's at risk for HA-VTE?

Several specific healthcare-associated factors increase the risk of developing DVT/PE. These include:

Injury to a vein, often caused by:

- Fractures

- Severe muscle injury

- Major surgery (particularly involving the abdomen, pelvis, hip, or legs)

Slow blood flow, often caused by:

- Confinement to bed

- Limited movement (e.g., a cast on a leg to help heal an injured bone)

Other healthcare associated factors:

- Such as a catheter located in a central vein

Additionally, certain factors put you at even greater risk of HA-VTE when combined with hospitalization, surgery, and/or immobility (limited movement):

- A previous blood clot

- An inherited clotting disorder

- A family history of blood clots

- Overweight or obesity

- Age 55 or older

- Taking hormonal medications

- Currently or recently pregnant (within 3 months of giving birth)

- Currently being treated for cancer

- Having other medical conditions like AIDS, anemia, arthritis, diabetes, high blood pressure, or heart disease

Times of increased risk

Recent studies have found:

- Among patients who developed a blood clot after surgery: 40% of blood clots occurred while they were still in the hospital, while 60% occurred up to 90 days after having left the hospital

- More than half of blood clots first identified in an outpatient setting are directly linked to a recent hospitalization or surgery

- A majority of healthcare providers do not reassess the risk of VTE at hospital discharge

Why is HA-VTE a public health problem?

Although anyone can develop a blood clot, more than a third of blood clots diagnosed each year are related to a recent hospitalization and most of these do not occur until after discharge.

- VTE is a leading cause of preventable hospital death in the United States.

- VTE is the fifth most frequent reason for unplanned hospital readmissions after surgery, overall, and the third most frequent among patients undergoing total hip or knee joint replacement. Patients with HA-VTE are 3 times more likely to be readmitted to the hospital than patients without HA-VTE.

- As many as 70% of cases of HA-VTE are preventable through prevention measures, such as use of blood thinning medications called anticoagulants, which help prevent blood from clotting, or use of compression stockings. Yet fewer than half of hospital patients receive these measures.

Protecting yourself from blood clots after hospitalization or surgery

Know the signs and symptoms of blood clots. Discuss your risks with your healthcare providers.

A blood clot occurring in the legs or arms is called deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Signs and symptoms of a DVT include:

- Swelling of the affected limb

- Pain or tenderness not caused by injury

- Skin that is warm to the touch, red, or discolored

If you have the signs or symptoms of a DVT, alert your healthcare provider as soon as possible.

A blood clot in the legs or arms can break off and travel to the lungs. This is called a pulmonary embolism (PE) and can be life threatening. Signs and symptoms of a PE include:

- Difficulty breathing

- Chest pain that usually worsens with a deep breath or cough

- Cough or coughing up blood

- Faster than normal or irregular heartbeat

Seek immediate medical attention if you experience any of the signs or symptoms of a possible PE.

Talk with your healthcare providers about factors that might increase your risk for a blood clot. Let them know if you or anyone else in your family has ever had a blood clot.

What is being done to reduce HA-VTE?

CDC recognizes the need to improve, advance, and guide prevention efforts to ensure that VTE prevention is a priority across the nation's healthcare settings. This topic was the focus of the January 15, 2013, CDC Public Health Grand Rounds and the information presented was summarized in a subsequent Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Nationally, CDC's work has guided and fostered VTE research and informed efforts throughout the country, including the Surgeon General's Call to Action on preventing VTE.

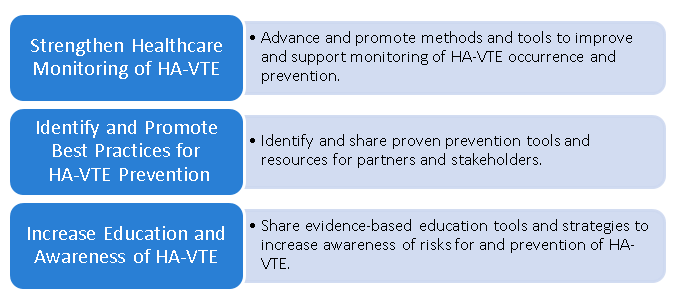

Currently, CDC is focusing on three main areas to promote, translate and implement strategies to prevent HA-VTE.

CDC has worked with two pilot programs at Duke University Medical Center and University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center to assess and better understand VTE occurrence. These two pilot programs will help CDC:

- Develop and evaluate methods and electronic tools to monitor the occurrence of VTE including those that are healthcare-associated

- Provide a more accurate picture of the health and economic impact of VTE (and HA-VTE), which will include identifying high-risk groups and settings

- Inform the development of improved healthcare monitoring tools to measure the success of prevention activities by tracking and monitoring trends in HA-VTE occurrence over time

CDC has worked with partners to develop and share information for patients, healthcare providers, and the public at large to improve both awareness of VTE and methods of preventing or managing blood clots.

The National Blood Clot Alliance (NBCA) in collaboration with CDC developed a digital public health education campaign called Stop the Clot, Spread the Word® to help address the lack of information on blood clots.

Stop the Clot, Spread the Word® was one of many CDC resources recognized in 2017 as an important asset in a collection of VTE educational resources published by The Joint Commission [PDF – 3.24 MB] The Commission accredits and certifies nearly 21,000 healthcare organizations in the United States.

The campaign web portal provides people with lifesaving information about blood clots, including the factors that increase the risk for blood clots, as well as their signs, symptoms, and prevention.

Resources

Preventing Hospital-Acquired Venous Thromboembolism: Based on quality improvement projects undertaken at the University of California, San Diego Medical Center and Emory University Hospitals, this guide assists quality improvement professionals in leading an effort to improve prevention of one of the most important problems facing hospitalized patients, venous thromboembolism.

- Kahn S, Morrison D, Cohen J, Emed J, Tagalakis V, Roussin A, Geerts W. Interventions for implementation of thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical and surgical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD008201-CD.

- Lam BD, Dodge LE, Datta S, Rosovsky RP, Robertson W, Lake L, Reyes N, Adamski A, Abe K, Panoff S, Pinson A, Elavalakanar P, Vlachos IS, Zwicker JI, Patell R. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for hospitalized adult patients: a survey of US health care providers on attitudes and practices. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2023 Aug 7;7(6):102168. doi: 10.1016/j.rpth.2023.102168. PMID: 37767063; PMCID: PMC10520566.

- Merkow RP, Ju MH, Chung JW, Hall BL, Cohen ME, Williams MV, Tsai TC, Ko CY, Bilimoria KY. Underlying reasons associated with hospital readmission following surgery in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(5):483-95.

- Neeman E, Liu V, Mishra P, et al. Trends and Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism Among Hospitalized Medical Patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2240373. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.40373

- Nelson RE, Grosse SD, Waitzman NJ, Lin J, DuVall SL, Patterson O, Tsai J, Reyes N. Using multiple sources of data for surveillance of postoperative venous thromboembolism among surgical patients treated in Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals. Thromb Res. 2015;135(4):636-42.

- Saber I, Adamski A, Kuchibhatla M, Abe K, Beckman M, Reyes N, Schulteis R, Pendurthi Singh B, Sitlinger A, Thames EH, Ortel TL. Racial differences in venous thromboembolism: A surveillance program in Durham County, North Carolina. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022 Jul 21;6(5):e12769. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12769. eCollection 2022 Jul.PMID: 35873215

- Society of Hospital Medicine, Maynard GA, Stein JM, US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Preventing hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2008.

- Tsai J, Grant AM, Beckman MG, Grosse SD, Yusuf HR, Richardson LC. Determinants of venous thromboembolism among hospitalizations of US adults: a multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0123842. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123842.

- Wendelboe AM, Campbell J, Ding K, Bratzler DW, Beckman MG, Reyes NL, Raskob GE. Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism in a Racially Diverse Population of Oklahoma County, Oklahoma. Thromb Haemost. 2021 Jun;121(6):816-825. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1722189. Epub 2021 Jan 10.PMID: 33423245

- Zeidan AM, Streiff MB, Lau BD, Ahmed SR, Kraus PS, Hobson DB, Carolan H, Lambrianidi C, Horn PB, Shermock KM, Tinoco G, Siddiqui S, Haut ER. Impact of a venous thromboembolism prophylaxis "smart order set": Improved compliance, fewer events. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:545-9.