What to know

Antibiotic-resistant infections are a major public health threat and can lead to initial treatment failures, a lengthier illness, and limited treatment options. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) helps scientists rapidly predict whether bacteria are resistant to antibiotics based on genetic information. In 2018, this information helped make the important distinction between two outbreaks occurring at the same time so public health officials could respond to each more effectively.

Overview

You or someone you know probably got sick from something you ate in the last year. While foodborne infections are often mild, they can be dangerous and costly, especially for people with weakened immune systems, children age 5 and younger, and adults 65 and older. People who become severely ill may require antibiotics to get well. Yet some types of foodborne infections are increasingly resistant to antibiotics. One common type of foodborne bacteria, Salmonella, causes an estimated 212,500 antibiotic-resistant infections in the United States every year, and its resistance to some antibiotics is increasing. Antibiotic-resistant infections are a major public health threat and can lead to initial treatment failures, a lengthier illness, and limited treatment options.

The National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria (NARMS), a public health surveillance system, tracks antibiotic-resistant bacteria that cause gastrointestinal and foodborne illness. WGS, a new technology, has made this task easier. WGS lets scientists rapidly predict whether bacteria are resistant to antibiotics based on genetic information. In 2018, this information helped make the important distinction between two outbreaks occurring at the same time so public health officials could respond to each more effectively.

Salmonella Newport: A tale of two outbreaks and rare resistance

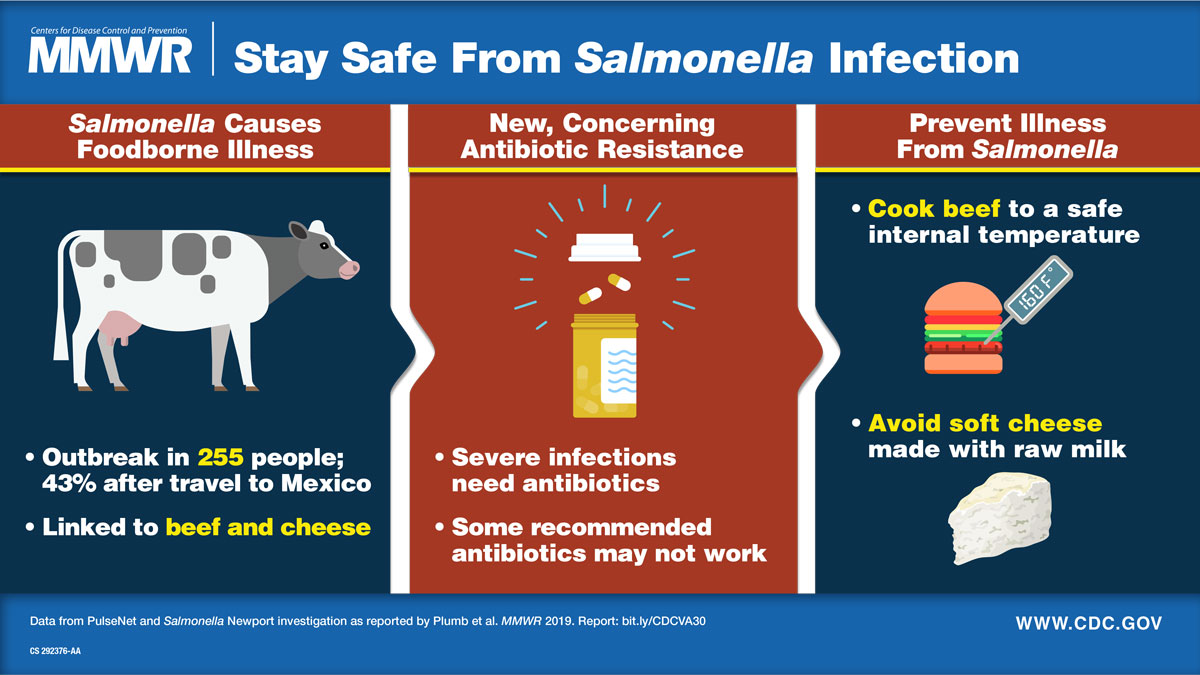

In October 2018, CDC and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food Safety and Inspection Service were investigating a large outbreak of Salmonella Newport infections linked to ground beef. When NARMS scientists used WGS to predict antibiotic resistance, they noticed that although most strains were susceptible to antibiotics, some were resistant to multiple antibiotics. This tipped off epidemiologists that two outbreaks were occurring simultaneously and led to the investigation of a distinct outbreak of multidrug-resistant Salmonella Newport with decreased susceptibility to azithromycin. Azithromycin is a recommended antibiotic for treatment of severe Salmonella infections. Salmonella with decreased susceptibility to azithromycin is a rare finding and occurs in fewer than 1 percent of Salmonella infections. State public health officials asked patients about recent food, animal, and travel exposures to find a common link for their infections. Illnesses were linked to beef consumed in the United States and Mexico and to soft cheese from Mexico, findings that suggested that cattle in both countries could be a source of this multidrug-resistant Salmonella. From June 2018 through March 2019, 255 people in 32 U.S. states became ill from this strain of Salmonella.

The future of resistance tracking

NARMS scientists can use WGS to predict antibiotic resistance in Salmonella and other pathogens much faster than with traditional methods. Combining this detailed genetic information with epidemiologic information helps scientists more precisely link illnesses to food or animal sources. In fact, every U.S. public health department is supported by CDC's Antibiotic Resistance Solutions Initiative to perform WGS on the enteric germs that NARMS tracks, including Salmonella, to rapidly identify and stop outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant infections.

Beyond its contributions to outbreak response, WGS helps scientists understand transmission, including how resistant strains get into the food supply. WGS strengthens the fight against the global health threat of antibiotic resistance.

Read more about the outbreak of multidrug-resistant Salmonella Newport in the August 2019 MMWR.