What to know

The SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 changes constantly as it replicates, and sometimes these mutations produce new variants. CDC collaborates with national and global public health partners to monitor the spread of variants and examine the changes in their genetic code through genomic sequencing. Here in the United States, CDC has vastly expanded the national capacity for genomic sequencing through supplemental support to state, local, and territorial public health laboratories and strategic investments in academic research projects.

A new variant identified

In fall 2021, while the world was still grappling with the Delta variant of the virus, scientists in Botswana detected a new COVID-19 variant, B.1.1.529. A few days later, scientists in South Africa encountered the same variant. South Africa reported the identification to the World Health Organization (WHO) and, on November 26, WHO classified B.1.1.529 as a variant of concern (VOC) and named it Omicron. Epidemiological and genetic data suggested this new variant would spread more easily than either the original virus that causes COVID-19 or the Delta variant.

Just five days later, on December 1, scientists in San Francisco identified the first case of infection caused by the Omicron variant in the United States. The patient had returned from South Africa in late November. The next day, scientists in Minnesota identified a second case in a person with no international travel history but who had attended a fan convention in New York City before having symptoms. By the end of December 2021, Omicron had become the most common SARS-CoV-2 variant in the United States.

Support for national surveillance

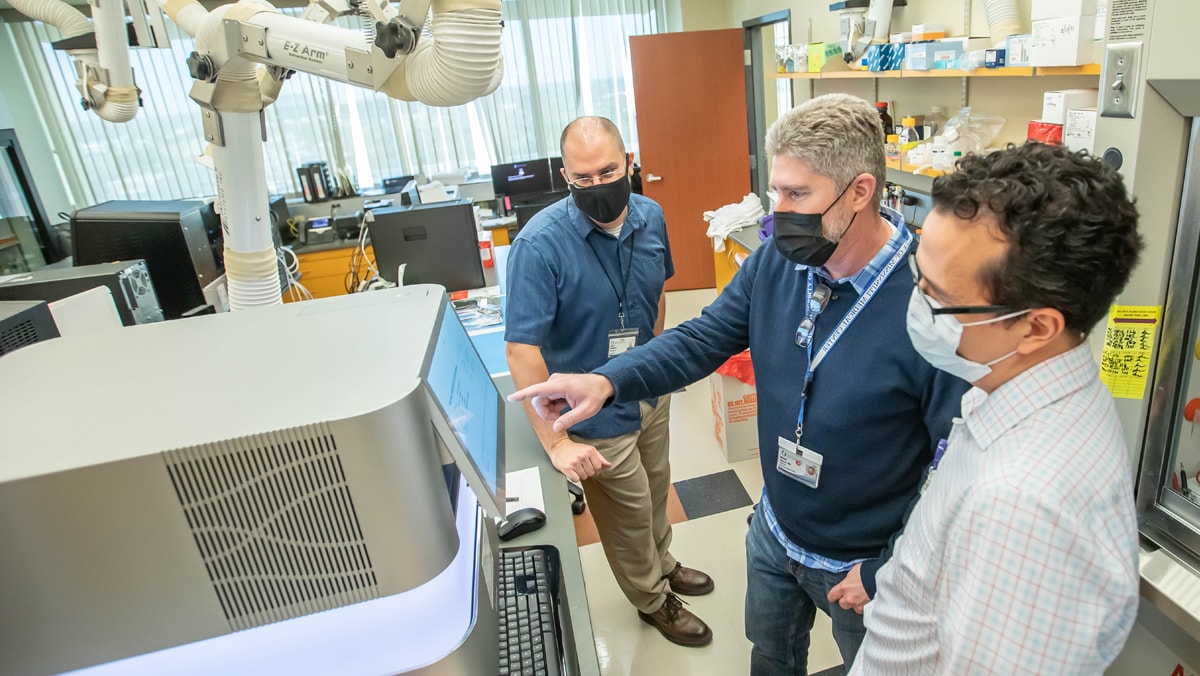

In May 2021, the Infectious Disease Division at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), received funding to track the evolution and spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the state. Leading the lab was physician and microbiologist Dr. Charles Chiu. "CDC's Broad Agency Announcement (BAA) award made it possible for us to sequence and identify variants in real-time, leading to the detection of the first case of Omicron variant infection in the United States," said Chiu. "This support was critical in establishing a highly productive 3-way collaboration between an academic health center (UCSF), testing company (Color Genomics), and local public health agency (San Francisco Department of Public Health) to monitor for the emergence of new variants and thus provide actionable information to guide public health interventions to limit spread of the virus in the community."

That award was one of 29 research projects CDC funded to provide more resources to laboratories in parts of the United States that might otherwise be "blind spots" for detecting new variants. "In the AMD program, we're genuinely excited about the opportunities that these research awards offer to support partnerships with universities and the private sector," said AMD Director, Dr. Gregory Armstrong. "We're making increasing use of this mechanism to fund initiatives with potential to improve public health." In addition to these research awards, CDC has already distributed over $430 million to state and local public health laboratories to increase their capacity for sequencing, with plans for additional funding from the American Rescue Plan in future years to continue tracking COVID-19 and other emerging pathogens of concern. The viral genomic data from public health laboratories and academic laboratories are combined with data from commercial diagnostic laboratories and CDC's National SARS-CoV-2 Strain Surveillance (NS3) Program for detailed analysis. All of these efforts represent a remarkable collaboration between academia, public health, and the private sector to present a more detailed picture of how the virus circulates.

Director of the Molecular Virology Laboratory at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Dr. Heba Mostafa, recognized the value of real-time genomic surveillance data on day one. "With the significant support of the BAA funding from the CDC, we were able to establish a unique pipeline of, not only real-time SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance, but also real-time clinical analysis, viral isolations, and cell culture-based variants' characterizations." Mostafa said, "We expanded our research team, accelerated our research, and were able to answer many questions, in real-time, with every wave of evolution of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern, from Alpha, to Delta, to Omicron."

The national surveillance program for SARS-CoV-2 is unprecedented in terms of scale. From the logistics of moving hundreds of thousands of samples across the nation to assembling the data being generated in hundreds of laboratories, there have been challenges to solve. To address some of the short-term and long-term challenges, CDC's AMD program launched the Pathogen Genomic Centers of Excellence (PGCoEs). The PGCoE network is improving connections between academia and public health and will support future genomic surveillance at the national and community levels.

"The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly had a devastating impact on the health of Americans. Unfortunately, due to significant racial health disparities in Mississippi, it has experienced one of the highest numbers of COVID-19 deaths per capita in the US," said Dr. Michael R. Garrett, Professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology with the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC). "Our recent work with the CDC has provided an immediate impact by allowing us to increase sequencing capacity to include geographically diverse regions, which at the peak of Omicron included 73/82 counties throughout Mississippi. Through support from the CDC and the Mississippi State Department of Health (MSDH), the UMMC's Molecular and Genomics Core Facility has played a major role in the state's SARS-CoV-2 variant surveillance."

Because it is the nature of viruses to change, new variants of SARS-CoV-2 are expected. There is a continuous and critical need to understand, track, and analyze the virus in real time and use the collected data to create effective public health strategies. Due to the partnerships formed in this response, the national surveillance program can better identify future challenges and respond to changing needs.