About

The Evidence to Recommendations (EtR) frameworks describe information considered in moving from evidence to ACIP vaccine recommendations.

Summary

Question:

Should vaccination with Moderna COVID-19 vaccine (2-doses, 25µg, IM) be recommended for children 6 months – 5 years of age, under an Emergency Use Authorization?

Should vaccination with Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (3-doses, 3µg, IM) be recommended for children 6 months – 4 years of age, under an Emergency Use Authorization?

Population:

Children ages 6 months – 4 years or 5 years

Intervention:

Moderna COVID-19 vaccine (mRNA-1273) 2-doses, 25µg, IM

-or-

Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) 3-doses, 3µg, IM

Comparison: No vaccine

Outcomes:

- Symptomatic laboratory confirmed COVID-19

- Hospitalization due to COVID-19

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

- Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection

- Serious adverse events

- Reactogenicity grade ≥3

Background

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has led to a global pandemic with substantial societal and economic impacts on individual persons and communities. In the United States, more than 85 million cases and more than 1,000,000 COVID-19-associated deaths have been reported as of June 14, 2022. Persons of all ages are at risk for infection and severe disease. While children <18 years of age infected with SARS-CoV-2 are less likely to develop severe illness compared with adults, children are still at risk of developing severe illness and complications from COVID-19 and contribute to transmission in households and communities. A disproportionate burden of COVID-19 infections and deaths occur among racial and ethnic minority communities, including among children. Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic/Latino and American Indian/American Native persons have experienced higher rates of disease, hospitalization and death compared with non-Hispanic Whites. This is likely related to inequities in social determinants of health that put racial and ethnic minority groups at increased risk for COVID-19, including income disparities, reduced access to healthcare, or higher rates of comorbid conditions.

On June 17, 2022, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for a 2-dose Moderna COVID-19 vaccine primary series for administration to children ages 6 months through 5 years. The FDA also authorized a 3rd primary series dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine to children ages 6 months through 5 years with certain kinds of immunocompromise. Furthermore, the FDA authorized an EUA for a 3-dose Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine primary series for administration to children ages 6 months through 4 years. Following FDA’s regulatory action, CDC expanded eligibly of COVID-19 vaccines to everyone ages 6 months and older on June 18, 2022.

Additional background information supporting the ACIP recommendation on the use of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for children ages 6 months through 4 years and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for children ages 6 months through 5 years can be found in the relevant publication of the recommendation referenced on the ACIP website.

Problem

| Criteria | Work Group Judgements | Evidence | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is the problem of public health importance? | Yes | Incidence:

As of June 14, 2022, there were more than 85 million total recorded cases of COVID-19 in the United States.1 Additionally, as of June 14, 2022, over 578,000 cases occurred among infants and more than 1.9 million cases occurred among children ages 1-4 years.2

Hospitalization:

Hospitalization rates increased during the Omicron surge to the highest rates yet seen during the pandemic. During 2022, hospitalization rates were higher among children ages 6 months to 4 years, than among children ages 5 – 11 years and adolescents ages 12 – 17 years.3

To further illustrate this point, during the Omicron surge, cumulative hospitalization rates increased more among children ages 6 months – 4 years than among older children and adolescents; and by March 2022 was higher among children 6 months to 4 years than among adolescents. Of course, during the Omicron surge, children ages 5-11 years and 12 – 17 years were eligible for COVID-19 vaccination.3

Mortality:

As of May 11, 2022, there were 202 COVID-19 related deaths reported to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) among children ages 6 months to 4 years, which made up 1.7% of all deaths among children in this age group.4

COVID-19 was a leading cause of death among children ages 0 to 4 years during the pandemic. From April 1, 2021 – March 31, 2022, COVID-19 would be in the top 10 leading causes of death overall and a leading cause of infectious disease deaths among infants less than 1 year and children ages 1 through 4 years when compared to causes of deaths during 2019 (i.e., pre-pandemic) (Reference and data updated with September 20, 2022 article version).5

Additionally, COVID-19-associated deaths were similar to or exceed the pre-vaccine-era burden of other now pediatric vaccine preventable diseases.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

|

Seroprevalence of infection-induced SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among children ages 6 months – 17 years:

Seroprevalence in all age groups increased substantially during the Omicron surge and children ages 6 months through 4 years who were not yet eligible for vaccination, had a larger increase in seroprevalence since December 2021 than children ages 5 – 11 years and adolescents ages 12 – 17 years. The rate of rise in seroprevalence was less steep between February 2022 and the combined March/April time point, when seroprevalence was estimated at 71%.12

Effectiveness of primary SARS-CoV-2 (non-Omicron) infection against Omicron re-infection:

In relation to the effectiveness of primary SARS-CoV-2 (non-Omicron) infection against Omicron re-infection, by time since primary infection or vaccination among Quebec residents Dec 2021-March 2022 in those ages 12 and older, those with prior infection, but not vaccinated, had the lowest effectiveness.13 Similar data were found for effectiveness of mRNA vaccination against COVID-19 hospitalization among adults previously infected. Risk of reinfection increases over time but is thought to be low in the early weeks to months following infection.14

Improved antibody response after vaccination:

Among children, COVID-19 vaccine induces a broader neutralizing antibody response compared with infection induced immunity. From a U.S. multicenter cohort, antibody profiles of unvaccinated pediatric patients hospitalized for COVID-19 were compared to profiles of vaccinated children. In contrast to those with SARS-CoV-2 infection, children vaccinated with two doses demonstrated higher titers against Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta and Omicron. The findings suggest that antibodies produced by prior SARS-CoV-2 infection (pre-Omicron) may not neutralize the currently circulating Omicron variant. This builds on evidence among adults that previous infection provides poor protection from infection with Omicron. Therefore, it is important to vaccinate children with prior infection to prevent both severe disease and future infections.15

|

Benefits and Harms

| Criteria | Work Group Judgements | Evidence | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| How substantial are the desirable anticipated effects? | Large | Moderna COVID-19 vaccine

Risk of symptomatic COVID-19 was reduced among persons ages 6 months – 5 years receiving two doses of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine compared to placebo, which was further supported by evidence from immunobridging (GRADE Tables 3a and 3b). Risk of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection was not statistically different between the vaccine and placebo groups (Grade Table 3c).

The phase 2/3 randomized controlled trial (RCT) for the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine demonstrated efficacy of the 2-dose regimen against symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed, COVID-19.1,2 The pooled efficacy among participants ages 6 months – 5 years with or without evidence of prior infection was 37.8% (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 20.9%, 51.1%). Efficacy was assessed a median of 2.5 months after receipt of a second dose.

Immunobridging data comparing geometric mean antibody titers (GMT) in children ages 6—23 months and 2—5 years to adults ages 18 – 25 years, for whom clinical efficacy was previously established, were provided in support of efficacy. In both age groups, 6—23 months and 2—5 years, the immune response to vaccine was noninferior to that observed in those ages 18 – 25 years, with a GMR of 1.28 (95% CI: 1.12, 1.47) in 6—23 months and 1.01 (95% CI: 0.88, 1.17) in 2 – 5 years.

Asymptomatic SAR-CoV-2 infection was defined as absence of symptoms and at least 1 of following among participants who were PCR negative at baseline: 1) Binding antibody level against SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein negative at Day 1 that becomes positive post-baseline or 2) positive RT-PCR test post-baseline at scheduled or unscheduled visit. Note that antibody levels were taken only on the immunogenicity subset in this trial.

Among children ages 6 months to 5 years, the vaccine efficacy (VE) against asymptomatic infection was 16% (95% CI:-18.5, 40.5).

Pfizer-BioNTech:

Risk of symptomatic COVID-19 was reduced among persons ages 6 months – 4 years receiving three doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine compared to placebo, which was further supported by evidence from immunobridging (GRADE Tables 3a and 3b).

The clinical trial for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine demonstrated efficacy of the three-dose regimen against symptomatic lab-confirmed COVID-19. 3,4 The pooled efficacy among participants ages 6 months – 4 years with or without evidence of prior infection was 80.0% (95% CI: 22.8%, 94.8%). Efficacy was assessed a median of 1.3 months after receipt of a third dose. Immunobridging data comparing geometric mean antibody titers (GMT) in children ages 6 – 23 months and 2 – 4 years to adults ages 16 – 25 years, for whom clinical efficacy was previously established, were provided in support of efficacy. The immune response to vaccine in children ages 6 – 23 months and those 2 – 4 years was noninferior to that observed in young adults ages 16 – 25 years, with a geometric mean ratio of 1.19 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.19) in children ages 6 – 23 months and a geometric mean ratio of 1.30 (95% CI: 1.13, 1.50) in children ages 2 – 4 years.

|

Direct evidence of efficacy against severe outcomes is not expected from early results from phase 3 studies. Vaccine efficacy in preventing hospitalizations and MIS-C may be inferred from observed efficacy against symptomatic COVID-19.

COVID-19 vaccines and seropositivity:

Omicron-wave surges of pediatric COVID-19 hospitalizations occurred even with high seroprevalence, suggesting previous infection alone is not sufficient to provide broad protection. There were no concerns identified in safety surveillance with vaccination of seropositive individuals. A recent update to Clinical Considerations states that people who recently had SARS-CoV-2 infection may consider delaying their COVID-19 vaccine primary series dose or booster by 3 months from symptom onset or positive test.5 A longer interval between infection and vaccination may result in an improved immune response to vaccination and risk of reinfection is low in the weeks to months following infection.

Numbers needed to vaccinate analysis:

The number needed to vaccinate was estimated based on vaccine benefits calculated per 1 million fully vaccinated with mRNA vaccine focusing on the age group: 6 months – 4 years. Pandemic average age-specific incidence rates were used with hospitalization rates from COVID-NET and case rates from case-based surveillance. 6,7 VE against hospitalization was assumed, ranging from 42 to 84%, based on the ratio of infection to severe disease seen in 5–11-year-olds applied to the VE against infection seen in 6 months – 4 years. The assumed VE against symptomatic infection ranged from 30%-60%, based on estimates from the clinical trials.2,4 A 120-day time horizon was used.

Among children ages 6 months through 4 years, 670 to 1,300 vaccinations are needed to prevent 1 case and 6,150 -12,300 vaccinations are needed to prevent 1 hospitalization over a 120-day period.

|

| How substantial are the undesirable anticipated effects? | Small | Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine:

Risk of serious adverse events was low but more common in the vaccine than the placebo group. Grade 3 reactogenicity was increased among persons receiving 2 doses of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine compared to placebo (GRADE table 3d and 3e).

Solicited injection-site reactions and systemic events within 7 days after vaccination were frequent and mostly mild to moderate. Systemic reactions were generally more frequent and severe after dose 2 compared with dose 1. Median onset of systemic reactions was 1 to 2 days post-vaccine receipt and they resolved in a median duration of 1 to 2 days.

Severe adverse reactions (grade ≥3, defined as interfering with daily activity) occurred more commonly after the vaccine (7.7%) compared with placebo (4.1%). The most common grade 3 local symptom reported by vaccine recipients was pain at the injection site (0.4%). The most commonly reported systemic reactions of grade 3 or higher after dose 2 were fever (2.6%) and irritability/crying (1.2%) among vaccine recipients ages 6–36 months and fever (3.1%) and fatigue (2.3%) among vaccine recipients ages 37 months–5 years. Generally, grade ≥3 reactions were more commonly reported after the second dose than after the first dose.

Adverse events classified as serious† were reported in more recipients of vaccine than placebo, overall (0.5% vs. 0.2%) and by system organ class; they represented medical events that occur in the pediatric population at a frequency similar to that observed in the study. No specific safety concerns were identified.

Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine:

Risk of serious adverse events was low and more common in the placebo than the vaccine group. Grade 3 reactogenicity was slightly higher among persons receiving 3 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine rather than placebo, but the difference was not significant (GRADE table 3d and 3e).

Solicited injection-site reactions and systemic events within 7 days after vaccination were frequent (47.8% reported any local reaction, and 63.8% reported any systemic reaction); the vast majority of reactions were mild to moderate. Median onset of systemic reactions was 1 to 2 days post-vaccine receipt and they resolved in a median duration of 1 to 2 days.

Severe adverse reactions (grade ≥3, defined as interfering with daily activity) occurred more commonly with the vaccine (4.3%) compared with placebo (3.6%). The most common grade 3 symptoms reported by vaccine recipients were fever (4.0%) and irritability (1.3%) among vaccine recipients ages 6–23 months and fatigue (0.8%) and fever (2.2%) among vaccine recipients ages 2–4 years.

Adverse events classified as serious† were reported in more recipients of placebo than vaccine, overall (1.5% vs. 1.0%) and by system organ class; they represented medical events that occur in the pediatric population at a frequency similar to that observed in the study. No specific safety concerns were identified.

|

Safety data showed an acceptable safety profile.

Post-marketing surveillance will be critical to detect any rare serious adverse events, which were not identified in the clinical trial.

Myocarditis in young children:

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, peaks in myocarditis hospitalizations were seen in infants (many cases can represent cardiomyopathy with genetic component) and adolescents (typically viral in etiology). In children, the annual incidence of myocarditis was 0.8 per 100,000 (66% were male and the median length of stay [LOS] was 6.1 days). However, in adolescents ages 15-18 years, the annual incidence was 1.8 per 100,000 in 2015 – 2016.8

Cardiac complications after SARS-CoV-2 infections:

Cardiac complications in the setting of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection in young children are uncommon. Most cardiac complications post-SARS-CoV-2 infection in infants are related to MIS-C, as 1.8% of MIS-C cases are found in children ages 6-11 months. Infants <1 year of age with MIS-C have severe cardiovascular involvement in ~55-65% of cases.9

Vaccine-associated myocarditis in children and adolescents:

Rates of myocarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination, if any, in young children is unknown. No cases occurred during clinical trials (n=7,804 with at least 7 days of follow-up). Based on the epidemiology of classic myocarditis and safety monitoring in children ages 5-11 years, myocarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in young children is anticipated to be rare. Underlying epidemiology of myocarditis is fundamentally different in infants. The dose used in young children is lower than the dose used in older children.

|

| Do the desirable effects outweigh the undesirable effects? | Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine:

The Work Group decided that the desirable effects of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine outweigh the undesirable effects.

Pfizer-BioNTech Vaccine:

The Work Group decided that the desirable effects of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine outweigh the undesirable effects.

|

||

| What is the overall certainty of this evidence for the critical outcomes? | Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine:

For the critical outcomes, the certainty of evidence was High for prevention of symptomatic COVID-19 assessed using direct efficacy, Moderate for symptomatic COVID-19 assessed using immunobridging, and Very Low for serious adverse events. For important outcomes, the certainty of evidence was Low for asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and High for reactogenicity.

Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine:

For the critical outcomes, the certainty of evidence was Very Low for prevention of symptomatic COVID-19 assessed using direct efficacy, Moderate for symptomatic COVID-19 assessed using immunobridging, and Very Low for serious adverse events. For important outcomes, the certainty of evidence was Moderate for reactogenicity.

|

Values

| Criteria | Work Group Judgements | Evidence | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Does the target population feel that the desirable effects are large relative to undesirable effects? | Varies | A survey designed by the CDC and University of Iowa/RAND Corporation to assess parental beliefs and attitudes toward pediatric COVID-19 vaccinations among children ages 6 months to 4 years collected data from February 2 – February 10, 2022, with a sample size of 2,048 respondents. Half of the parents of children ages 6 months – 4 years said they definitely or probably would vaccinate their child, once they become eligible. Only a fifth of all respondents said they would get their child ages 6 months through 4 years vaccinated within 3 months after becoming eligible. Furthermore, parents did not have a strong preference for a 2-dose or 3-dose series, with 20% of parents preferring a 3-dose series and 28% preferring a 2-dose series. Moreover, the percentage of parents of children ages 6 months through 4 years who definitely or probably will vaccinate their child, when eligible, significantly varied by gender (51% males vs. 44% females), race and ethnicity (53% Hispanic/Latino vs. 46% Non-Hispanic Black and 43% Non-Hispanic White) and education (60% ≥ Bachelor’s degree vs. 40% Some college/Trade school and 42% ≤ High school degree).1

The National Immunization Survey-Child COVID Module (NIS-CCM) is a random-digit-dial cellular telephone survey of households with children that began on July 22, 2021. This survey assessed parental intent for vaccination of children ages 6 months – 4 years. In May 2022, one-third (33.5%) of parents reported they definitely will get their child 6 months–4 years vaccinated. Additionally, in May, a smaller percentage (29.6%) of parents of children 6-23 months reported definite intent to vaccinate their child compared to parents of children 2-4 years (35.4%).2

Additional survey data reports, one in five parents of children under 5 (18%) are eager to vaccinate their child and say they will do so right away once a COVID-19 vaccine is authorized for their age group.3

Reflecting vaccine intentions among parents of children from different age groups, a survey conducted prior to safety and efficacy information were available on COVID-19 vaccines in young children found that most parents of older children feel better informed, with three-fourths of parents of adolescents ages 12 -17 years and two-thirds of parents of children ages 5-11 years saying they have enough information about vaccine safety and effectiveness for their age group.4

|

|

| Is there important uncertainty about or variability in how much people value the main outcomes? | Probably important uncertainty or variability | Considering parental attitudes and intentions toward pediatric COVID-19 vaccinations, a third of parents of children ages 6 months through 4 years said they definitely or probably would not vaccinate their child, once eligible.1

In relation to the National Immunization Survey-Child COVID-Module (NIS-CCM), 17.2% of parents report they definitely will not get their child vaccinated. There was no difference in the percentage reporting definitely/probably will not get their child vaccinated between parents of children ages 6 – 23 months and 2 – 4 years.2

In relation to vaccination intentions, almost four in ten parents of children under 5 say they want to “wait and see” before getting their young child vaccinated (38%). Another four in ten parents are more reluctant to get their young child vaccinated with 11% saying they will only do so if they are required and 27% saying they will “definitely not” get their child under 5 vaccinated for COVID-19.3

Lack of available information may be a factor in parents’ reluctance to get their youngest children vaccinated right away. A survey conducted prior to safety and efficacy information were available on COVID-19 vaccines in young children found that a majority of parents of children under five say they don’t have enough information about the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines for children in this age group (56%).4

|

Acceptability

| Criteria | Work Group Judgements | Evidence | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is the intervention acceptable to key stakeholders? | Yes | Pediatricians are the top trusted source for information about COVID-19 vaccines for children among parents across community types, with around three-quarters of each group saying they trust their child’s pediatricians a great deal or a fair amount. While majorities of urban and suburban parents also trust their local health department and the CDC, rural parents are somewhat less trusting of some of these sources (50% trust their local public health department and 45% trust the CDC). Fewer parents say they trust their child’s school or daycare or other parents they know for reliable information on the COVID-19 vaccine for children.1

As of early May 2022, more than two-thirds of Vaccines for Children (VFC) program providers were enrolled as COVID-19 vaccine providers. For young children, encouraging VFC providers to enroll as COVID-19 vaccine providers and encouraging enrolled providers to administer the COVID-19 vaccine becomes even more critical to ensure access to COVID-19 vaccine as well as all other routine childhood vaccines. Additionally, continued coordination through jurisdictions will be needed for the Indian Health Services (IHS), Tribal and Urban Indian Health Programs, and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) programs. Similar to the COVID-19 vaccine rollout for 5 – 11-year-olds, jurisdictions should plan their ordering strategy and identify priority locations to vaccinate children ages 6 months – 4 years or 6 months – 5 years. The goal is an efficient rollout resulting in equitable vaccine access for young children in the initial weeks when demand is likely to be higher.2

Nearly 18,000 non-pharmacy providers have administered the COVID-19 vaccine to children ages 5-11 years and approximately 4,000 pharmacies have expressed interest in administering the COVID-19 vaccine to children ages 5 years and younger, which indicates that approximately 85% of children ages 5 years and younger will live within 5 miles of a vaccine provider for COVID-19 vaccines.

|

Feasibility

| Criteria | Work Group Judgements | Evidence | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|

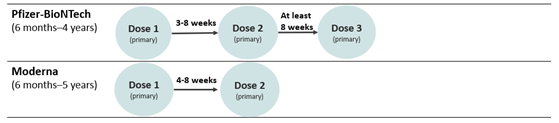

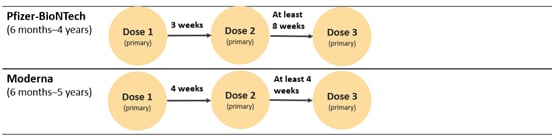

| Is the intervention feasible to implement? | Probably yes | The Moderna vaccine for children ages 6 months – 5 years:

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for children ages 6 months – 4 years:

The packaging configuration for both vaccine products is expected to be 10-dose vials in cartons of 10 vials each (100 doses total) with a minimum order quantity of 100 doses per product. Ancillary supplies will be provided for both vaccine products, including 1- inch needles and syringes to support 100 doses of vaccine. Diluent will be provided with ancillary supplies to support 100 doses per kit for the Pfizer vaccine.1 |

Resource Use

| Criteria | Work Group Judgements | Evidence | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is the intervention a reasonable and efficient allocation of resources? | Yes | No studies were found that evaluated cost-effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination among children. Studies in adults have shown COVID-19 related healthcare costs could be billions or trillions of dollars.1,2 Given this, COVID-19 vaccines overall are likely cost-saving.3-5 In a study conducted by Pfizer, they estimated that Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine use in individuals ages ≥12 years averted 9 million symptomatic cases, almost 700,000 hospitalizations and over 110,00 deaths resulting in $30.4 billion direct healthcare cost savings.6 At this time, vaccines will be available at no cost to the recipient. Cost-effectiveness is not a primary driver for decision making during a pandemic but will be reassessed in the future. |

Equity

| Criteria | Work Group Judgements | Evidence | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| What would be the impact of the intervention on health equity? | Probably no impact | In relation to COVID-19 weekly cases per 100,000 population by race and ethnicity among children ages 0 – 4 years from March 1, 2020 – May 8, 2022, there was an increase among all children during the Omicron surge, but there was a considerable increase among American Indian/Alaska Native children.1

In relation to the National Immunization Survey-Child COVID-Module (NIS-CCM) conducted in May 2022, parental intent to vaccinate children ages 6 months – 4 years varied by race and ethnicity, household income, metropolitan statistical area with lower intent among parents residing in rural areas, and receipt of influenza vaccination status with a much higher intent among those who previously received a flu vaccine.2

There were also HHS/ASPA focus groups that were conducted from March – April 2022 to assess vaccination intentions among parents of children under 5 as part of the COVID-19 Public Education Campaign. There were 18 focus groups with 4-6 participants in each group and demographics of parents varied by Black, Hispanic/Latino, and the overall population without a specific race and ethnicity focus. Some groups were composed of parents ‘Ready to Vaccinate’ and others ‘Waiting to Vaccinate.’ Participants shared thoughts and opinions about the COVID-19 pandemic regarding their child as well as thoughts and opinions about getting their child a COVID-19 vaccine when it is authorized and available.

Black parents of children ages 6 months – under 2 years:

Hispanic parents of children ages 6 months – under 2 years:

Overall population of parents of children ages 6 months – under 4 years:

Black parents of children ages 2 years – under 5 years:

Hispanic parents of children ages 2 years – under 5 years:

Overall population of parents of children ages 2 years – under 5 years:

Summarizing the major themes that were seen in the focus groups, parents personal experience with COVID (for themselves and for their children) informs how they view the importance of the vaccine. If their children already had COVID, and it was mild, they aren’t worried about immediately vaccinating. However, if they or their child had severe COVID, they are more amenable to getting vaccinated to avoid that experience from recurring. Additionally, the pervasive idea that kids are not at high risk of getting COVID or having severe outcomes from COVID also informed vaccination intentions among parents. Moreover, time is a major barrier for most parents, such as the amount of time the vaccines have been in production, myth of the vaccines being rushed, wanting time for their children to grow and develop and taking time after approval to see how things go for other people before making a final decision.

CDC and doctors are trusted sources for providing information regarding vaccination and COVID-19. Although, some participants have been told mixed information by providers about whether to vaccinate their children under 5 years of age. Parents want to discuss both pros and cons of vaccination and avoid ads or messages that are overly simplistic or positive, such as incorporating more information into communications that provide reassurance about possible side effects. Additionally, ads need to include imagery that is representative of the specific age group. It is important to include diversity in racial and ethnic groups, gender, parents (moms and dads should be shown). Furthermore, public health and clinical trial research must be inclusive of historically marginalized populations, from before research initiation through completion and dissemination.3

Communities can play an integral role in improving equity in childhood vaccination. Pediatricians are often the providers who vaccinate children, and many do this through the federally funded Vaccines for Children (VFC) program. However, pediatricians are not the only providers who can vaccinate children. In many areas, pharmacies and community clinics, such as Federally Qualified Health Centers, rural health clinics, and community health centers also administer vaccines for children, and some of these are also VFC providers. Many schools and school districts partner with health departments, pharmacies, other healthcare providers and trusted community representatives to hold vaccine clinics in schools to vaccinate children who may not otherwise have access. Community organizations, including faith-based organizations, can serve as vaccination sites or as informational resources to help families find community-based vaccination sites.4

|

Work Group Interpretation Summary

The Work Group discussed each mRNA COVID-19 vaccine primary series compared to no vaccine. Both mRNA COVID-19 vaccine primary series in young children met the non-inferiority endpoints, provide protection against symptomatic COVID-19 disease, and are expected to provide higher protection against severe disease. Two vaccine options in this population may allow parents and providers a choice, which may increase uptake and acceptability.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, among U.S. children ages 6 months–4 years of age, there have been over 2 million cases, over 20,000 hospitalizations and over 200 deaths. COVID-19 can cause severe disease and death among children, including children without underlying medical conditions. Future surges will continue to impact children, with unvaccinated children remaining at higher risk of severe outcomes. As with all other age groups, priority is vaccination of unvaccinated individuals. Expansion of vaccine recommendations down to children 6 months of age now allows 18.7 million children to receive primary COVID-19 vaccine series.

Below is an image of the new pediatric schedule for children ages 6 months–5 years:

Children who are NOT moderately or severely immunocompromised

Children who ARE moderately or severely immunocompromised

The current data are for a 2-dose (Moderna) or 3-dose (Pfizer-BioNTech) primary series. As with all other age groups, it is likely that a booster dose will eventually be needed for both mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in young children. CDC will monitor post-authorization vaccine effectiveness studies to help determine this timing and subsequent need for boosters with an acknowledgement that immunocompromised children may also need additional doses for optimal protection. CDC will watch this data very closely and can update recommendations as needed. As with all ages, post-authorization safety and effectiveness monitoring will be critical. Platforms are in place to monitor vaccine effectiveness and results will be communicated publicly as soon as possible. Timing will depend on vaccine uptake, as well as COVID-19 incidence. Additionally, COVID-19 vaccines are being administered under the most intensive vaccine safety effort in U.S. history. Smartphone-based safety monitoring or v-safe is a CDC smartphone-based monitoring program for COVID-19 vaccine safety in the U.S. V-safe uses text messages and web surveys, which allows parents to complete surveys on behalf of their child. Surveys solicit how the child feels after COVID-19 vaccination, including local injection site reactions (i.e., pain, redness, and swelling), systemic reactions (i.e., fatigue, headache, and joint pain) and health impacts (unable to perform normal daily activities, missed school or work, or received care). Surveys have specific questions for young, non-verbal children as well. Healthcare providers can also help by promoting v-safe in their practice through information sheets, posters and QR codes. To register or access your account go to https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/v-safe/index.html.

For more information, the Interim Clinical Considerations guidance for use of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine primary series in children ages 6 months–5 years and the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine primary series in children ages 6 months–4 years is linked here: Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines | CDC

Balance of consequences (Moderna)

Desirable consequences clearly outweigh undesirable consequences in most settings

Is there sufficient information to move forward with a recommendation? Yes

Balance of consequences (Pfizer-BioNTech)

Desirable consequences clearly outweigh undesirable consequences in most settings

Is there sufficient information to move forward with a recommendation? Yes

Draft recommendation (text)

On June 18, 2022, ACIP voted (12-0) in favor of recommending:

A two-dose Moderna COVID-19 vaccine series (25µg) for children ages 6 months through 5 years, under the EUA issued by FDA

On June 18, 2022, ACIP voted (12-0) in favor of recommending:

A three-dose Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine series (3µg each) for children ages 6 months through 4 years, under the EUA issued by FDA

Final deliberation and decision by ACIP

Final ACIP recommendation

ACIP recommends the intervention.

The Moderna COVID-19 vaccine is recommended for children 6 months through 5 years of age under an Emergency Use Authorization.

ACIP recommends the intervention.

The Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine is recommended for children 6 months through 4 years of age under an Emergency Use Authorization.

References

Problem

- COVID Data Tracker, https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailytrendscases. Accessed 6/16/2022

- COVID Data Tracker, https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographicsovertime. Accessed 6/14/2022

- COVID-NET, https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/COVIDNet/COVID19_3.html. Accessed 5/21/2022

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/index.htm. Accessed 5/14/22

- Preprint: Flaxman, S., et al. (2022). "Covid-19 is a leading cause of death in children and young people ages 0-19 years in the United States." medRxiv: 2022.2005.2023.22275458. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.23.22275458v4 Note: Preprint was updated after ACIP meeting

- Vogt TM , Wise ME, Bell BP, Finelli L. Declining hepatitis A mortality in the United States during the era of hepatitis A vaccination. J Infect Dis2008; 197:1282–8.

- National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System with additional serogroup and outcome data from Enhanced Meningococcal Disease Surveillance for 2015-2019.

- Meyer PA, Seward JF, Jumaan AO, Wharton M. Varicella mortality: trends before vaccine licensure in the United States, 1970-1994. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(2):383-390. doi:10.1086/315714

- Roush SW , Murphy TV; Historical comparisons of morbidity and mortality for vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298:2155–63.

- Glass RI, Kilgore PE, Holman RC, et al. The epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea in the United States: surveillance and estimates of disease burden. J Infect Dis. 1996 Sep;174 Suppl 1:S5-11.

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/index.htm. Accessed 5/14/22

- Clarke K, Kim Y, Jones J et al. Pediatric Infection-Induced SARS-CoV-2 Seroprevalence Estimation Using Commercial Laboratory Specimens: How Representative Is It of the General U.S. Pediatric Population? (April 26, 2022). SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4092074 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4092074

- Carazo S, Skowronski DM, Brisson M, et al. "Protection against Omicron re-infection conferred by prior heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection, with and without mRNA vaccination" medRxiv, May 2022. Protection against Omicron re-infection conferred by prior heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection, with and without mRNA vaccination | medRxiv

- Plumb ID, Feldstein LR, Barkley E, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination in Preventing COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Among Adults with Previous SARS-CoV-2 Infection — United States, June 2021–February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:549-555. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7115e2

- Tang J, Novak T, Hecker J, et al. "Cross-reactive immunity against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is low in pediatrics patients with prior COVID-19 or MIS-C." Nature Communications. (2022) 13:2979. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30649-1

Benefits and harms

- Food and Drug Administration. Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.fda.gov/media/144636/download

- Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE): Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine for Children Aged 6 Months–5 Years https://wcms-wp.cdc.gov/acip/grade-evidence-tables-recommendations-in-mmwr/grading-recommendations-covid-19-moderna-vaccine-6-months-5-years.html

- Food and Drug Administration. Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.fda.gov/media/150386/download

- Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE): Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine for Children Aged 6 Months–4 Years https://wcms-wp.cdc.gov/acip/grade-evidence-tables-recommendations-in-mmwr/grading-recommendations-covid-19-pfizer-biontech-vaccine-6-months-4-years.html

- Clinical Guidance for COVID-19 Vaccination | CDC

- https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#covidnet-hospitalization-network

- https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographicsovertime

- Vasudeva et al. Am J Cardiology 2021 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002914921002617

- MIS-C National Surveillance Data, provided by Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome Unit, Epidemiology & Surveillance Task Force, CDC

Values

- CDC and University of Iowa/RAND survey, unpublished

- NIS-CCM estimates (5-17 years) available on COVIDVaxView at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/covidvaxview/interactive.html

- KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/dashboard/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-dashboard/#parents Accessed May 25, 2022

- KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: April 2022. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-april-2022 Accessed May 25, 2022

Acceptability

- KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Winter Update on Parents' Views (November 8-23, 2021). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-vaccine-attitudes-rural-suburban-urban/ Accessed March 7, 2022

- CDC. Updated Pediatric COVID-19 Vaccination Operational Planning Guide – Information for the COVID-19 Vaccine for Children 6 Months through 4 years old and/or COVID-19 Vaccine for Children 6 Months through 5 Years Old. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/Pediatric-Planning-Guide.pdf Accessed June 1, 2022

Feasibility

- Updated Pediatric COVID-19 Vaccination Operational Planning Guide – Information for the COVID-19 Vaccine for Children 6 Months through 4 Years Old and/or COVID-19 Vaccine for Children 6 Months through 5 Years Old. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/Pediatric-Planning-Guide.pdf Accessed June 1, 2022

- Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine Products. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/Pfizer-Pediatric-Reference-Planning.pdf Accessed June 16, 2022

Resource Use

- Bartsch et al https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00426

- Cutler and Summers. JAMA https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2771764

- Bartsch et al. JID https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/224/6/938/6267841?login=true

- Kohli et al. Vaccine https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X2031690X

- Li et al. Int JID https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971222001680

- Di Fusco et al Full article: Public health impact of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) in the first year of rollout in the United States (tandfonline.com)

Equity

- CDC COVID Data Tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographicsovertime Accessed May 31, 2022

- CDC/NCIRD, VTF Research Team, HHS/ASPA COVID-19 Public Education Campaign, Unpublished data

- CDC Vaccines and Immunizations. Equity in Childhood COVID-19 Vaccination. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/planning/children/equity.html Accessed June 1, 2022